Many privately insured people with an urgent medical problem go to hospital emergency departments (EDs) even though they could be treated safely and at lower cost elsewhere. Understanding why insured patients decide to seek care in EDs rather than other settings can help purchasers and payers safely guide patients to less-costly care. Patients’ perception of the severity of their medical problem and who they first contact for help or advice are the factors most associated with whether they seek emergency care, according to a study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) based on a 2012 survey of 8,836 active and retired nonelderly autoworkers and their spouses. Nearly a quarter of people reported having an urgent medical problem in the three months before the survey, and almost half (44%) of those with an urgent condition ultimately went to an emergency department for treatment. Of people with an urgent problem, nearly half first contacted their regular source of care—typically a primary care clinician—and those patients were less likely to go to emergency departments. And, patients who sought care in the ED directly—without a referral from their primary doctor—were more likely to report problems communicating with their doctor, getting timely appointments and obtaining referrals to high-quality specialists. In addition to encouraging patients to seek care in the most appropriate setting, interventions to reduce avoidable ED use could focus on making access to urgent care through primary care providers a more appealing option for patients.

- Perceived Urgency, Not Convenience, Fuels ED Use

- Patients Believe They Have True Emergencies

- If Primary Care Is Accessible, People Will Come

- The Doctor Will See You…

- Health Status Is a Factor in ED Use

- Policy Implications

- Notes

- Data Source

- Funding Acknowledgement

- Supplementary Table

Perceived Urgency, Not Convenience, Fuels ED Use

Safely reducing avoidable emergency department use by directing patients to less-costly care settings is a priority for many purchasers and payers. Understanding why insured patients go to emergency departments rather than other care settings when faced with an urgent medical issue is critical to redirecting patients to timely, appropriate care.

Contrary to the idea that convenience prompts many insured people to seek care in emergency departments, those most likely to use EDs believe they urgently need medical attention, according to the 2012 Autoworker Health Care Survey (AHCS) funded by the National Institute for Health Care Reform and conducted by HSC (see Data Source). Overall, 23 percent of current and retired autoworkers and their spouses under age 65 experienced an urgent medical problem in the three months before the survey.1 That is, they called a doctor’s office or went to an emergency department or urgent care center for a health problem that was not a routine or planned visit.

Only rarely did respondents cite convenience as a reason for choosing ED care. Moreover, people who reported that their primary doctor offered rapid access to advice and visits were significantly less likely to use emergency departments and instead relied on their primary clinician for urgent medical needs. However, despite their relatively comprehensive health coverage, the majority of autoworkers indicated they lacked this level of primary care access.

Patients often perceive the need to get medical care right away—or within a day or two—to address an urgent problem; these needs are frequently concerning or bothersome but rarely life threatening.2 Shifting patients from emergency departments to other care settings can be a difficult task, and interventions to reduce ED utilization have had varying success.3 Many interventions have focused on identifying primary care clinicians for ED patients who lack a usual source of care.4 Less is known about how patients who already have a usual source of care choose where to get care for an urgent medical problem, even though these patients comprise the majority of ED users.5

The AHCS provides an opportunity to examine why privately insured patients—many with a usual clinician for routine care needs—decide to go to emergency departments. Many also had cost-sharing incentives through copayments or deductibles to avoid EDs for less-severe needs.6 Autoworkers also typically benefit from sick-leave policies that allow them to seek care during working hours, removing another barrier to accessing care in settings other than EDs.

This Research Brief examines the characteristics of privately insured people with an urgent medical problem, describes the initial steps they take when addressing urgent medical problems, reviews why patients choose emergency departments for care, and discusses possible clinical and policy interventions that might avert avoidable ED use.

Back to Top

Patients Believe They Have True Emergencies

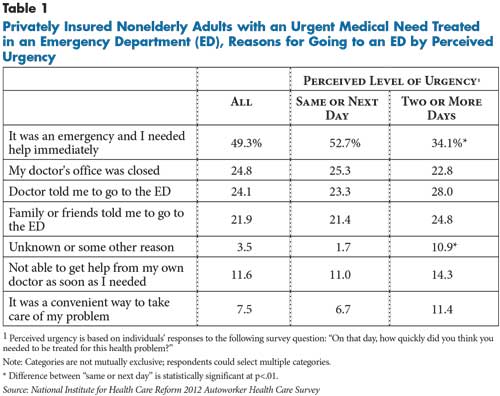

Despite popular perceptions that many patients deliberately use emergency departments for primary or routine care,7 autoworkers most commonly reported seeking ED care out of genuine concern for their health. Nearly half (49%) reported going to an emergency department in part because they believed their medical problem was an emergency and required immediate attention (see Table 1). And 30 percent indicated this was their sole reason, by far the most common response (finding not shown). In contrast, relatively few people cited convenience as a factor in deciding to go to an emergency department. About 7 percent indicated using an ED was driven partially by convenience, but less than 2.5 percent cited convenience as the sole reason for choosing an ED. About one in four people reported their doctor’s office was closed when they needed help, and close to a quarter indicated their physician instructed them to go to an emergency department.

People’s perception of the severity of their condition and how quickly they needed help were the factors most strongly associated with their decision to go to an ED, even after accounting for health status and other personal characteristics. People who believed they needed to see a clinician within a day were more likely to go to an ED than those who believed their problem could wait two or three days (30% vs. 20%, findings not shown). Patients’ level of concern predicted their use of emergency department care even when they initially contacted their personal physician. Among those who first contacted their primary physician, patients who believed they needed to be seen the same or next day were more than twice as likely to be referred to the ED as those who believed they could wait longer. People who believed they needed to be seen sooner also were less than half as likely to have their problem managed over the phone. And, people with a greater sense of urgency were half as likely to contact their doctor, reducing their opportunity to be directed to another care setting.

Back to Top

If Primary Care Is Accessible, People Will Come

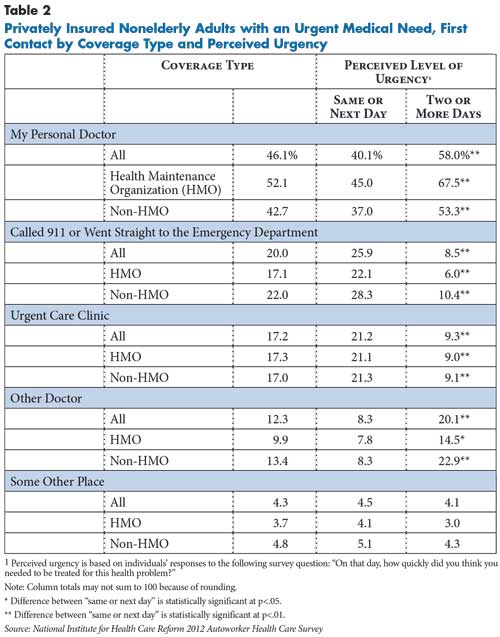

Many people with urgent medical needs tried to contact their primary physician. When first deciding to seek medical care for an urgent problem—either a new problem or aggravation of an existing problem—nearly half of all patients first contacted their physician for help or advice (see Table 2). Another 20 percent called 911 or went straight to the ED, and 17 percent first contacted or visited an urgent care center. People with coverage through a health maintenance organization (HMO) were more likely to contact their doctor when seeking urgent care (52% v. 43%) and were less likely to call 911 or go straight to the ED (17% vs. 22%).

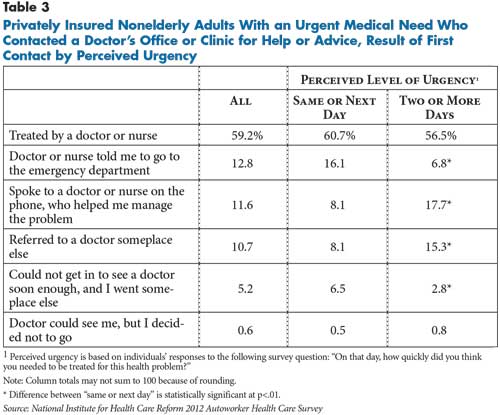

Overall, those who first contacted their doctor were much less likely to go to an emergency department than other people. Among the 75 percent of patients with an urgent need who contacted a doctor’s office or clinic, nearly 60 percent were treated by a doctor or nurse in an office setting and another 12 percent were able to have their issue managed over the phone (see Table 3). Almost a quarter of patients were referred elsewhere—more than half of these patients were instructed to go to the ED.

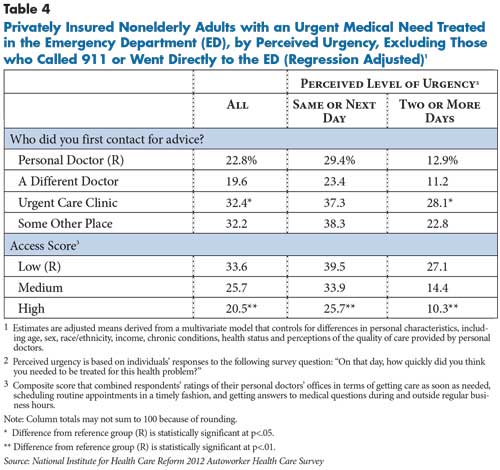

Overall, more than four in 10 people with an urgent medical problem ultimately were treated in an emergency department (findings not shown). However, patients who initially contacted their personal physician—or another doctor—were less likely to end up receiving ED care compared with those who contacted an urgent care clinic or some other place, even after accounting for other factors. Specifically, 23 percent of people who contacted their personal doctor ended up in the ED vs. 32 percent of those who contacted an urgent care center and 32 percent who contacted, for example, a walk-in clinic (see Table 4).

Back to Top

The Doctor Will See You…

Nearly a third of autoworkers said they usually were unable to get an appointment with their personal physician as soon as needed, and nearly half said they usually could not get timely answers to questions about their care when they called their physician in the past 12 months. While the substantial share of patients referred to EDs by physicians may reflect the severity of their complaints, it also may indicate that their doctor was unable to see them in a timely manner or provide the full range of services they would likely need.8 Understanding why and how community-based physicians use ED referrals is important in determining whether these patients’ needs could be met in a lower-cost setting.

Patients’ self-described level of access to their primary clinician played an important role in determining where they sought care for an urgent medical problem. People who rated their physicians’ offices highly in terms of getting care as soon as needed, scheduling routine appointments in a timely fashion, and getting answers to medical questions during and outside regular business hours were also less likely to go to EDs, even after accounting for other factors.9 This finding is particularly notable because patients who have tested these aspects of their clinician’s practice likely have done so because of illness, so they would be expected to have more acute medical needs that could not be met outside of an ED.

Back to Top

Health Status Is a Factor in ED Use

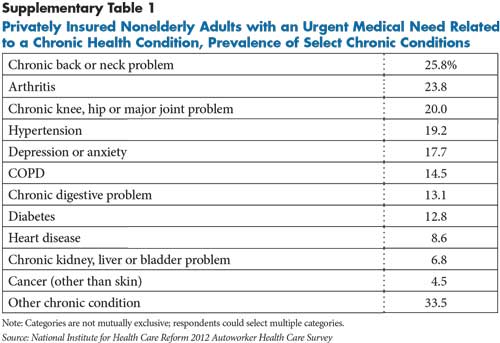

People who sought care for an urgent problem were more likely to report being in fair or poor physical or mental health and suffered from more chronic conditions compared with the overall autoworker population (findings not shown). Indeed, nearly 60 percent of people with an urgent medical problem indicated that their problem was related to a chronic health condition—most commonly musculoskeletal problems or high-blood pressure (see Supplementary Table 1). People who sought care for an urgent problem also were higher users of a broad spectrum of medical services: They had more ED visits and hospitalizations and more visits to primary care and specialty physicians, likely reflecting their poorer health status (findings not shown).

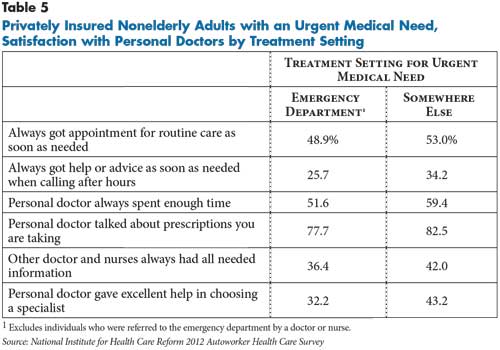

Among patients with urgent-care needs, those who self-referred to the ED—in other words, they were not told to go by a doctor or nurse—were less likely to report being able to get a timely appointment for routine care or get help or advice when they called their physician’s office after hours (see Table 5). They also were less likely to report that their primary physician spent enough time with them during visits, reviewed their prescriptions with them, or that their other providers had needed information from their primary clinician.

Back to Top

Policy Implications

When privately insured people believe they have an urgent medical problem and cannot access their usual physician as quickly as they believe necessary, they frequently will go to hospital emergency departments. Despite having relatively comprehensive insurance and, in most cases, relationships with a usual physician, many respondents believed their physicians did not provide timely access to care or assistance. Given this, expanding health coverage and linking patients to primary care practices may have less impact for insured individuals than expected on ED utilization without improved access to lower-cost settings that can provide a moderate intensity of care and urgent response time.

Some health care delivery system innovations, such as patient-centered medical homes, have emphasized improving timely access using a variety of approaches, including same-day appointments, and some research indicates the approach can reduce emergency department utilization.10

Other programs, such as Kaiser-Permanente’s 24/7 nurse-advice line—staffed with nurses who can access the patient’s medical record and communicate directly with the practice to schedule an appointment—may be helpful for patients who have trouble securing timely appointments themselves.

This study, along with other research, indicates that relying solely on financial incentives to alter patients’ sense of urgency when faced with an unexpected medical problem and influence where they go for help will be challenging.11 In this study, most respondents already had strong incentives to avoid unneeded ED care because their benefit design included either deductibles or higher copayments for ED visits that did not result in hospital admission and lower copayments for primary care and urgent care center visits.

ED care has obvious limitations for meeting patients’ less-emergent needs—it is resource-intensive, contributes to care fragmentation and, by definition, is unsuited to providing ongoing or preventive care. Policy makers and purchasers seeking to limit potentially avoidable ED use and redirect patients to other settings have identified emergency departments’ 24/7 availability as an important factor that may drive patients to EDs. Less noted, however, is some evidence suggesting that patients who seek care in emergency departments often report they are satisfied with their experience,12 and, in some cases, even perceive that EDs offer higher-quality care than their usual clinicians.13 These perceptions pose an additional challenge to reducing avoidable ED use.

Along with financial incentives to deter avoidable ED use, other approaches may be helpful. For example, educational interventions aimed at high-utilizing patients with chronic conditions that put them at higher risk of urgent medical problems may help guide patients to alternative care settings. Last but not least, ensuring access to lower-cost settings that can provide a moderate intensity of care and urgent response time likely could reduce emergency department use.14

Back to Top

Notes

Back to Top

Data Source

This Research Brief presents findings from the 2012 Autoworker Health Care Survey (AHCS) sponsored by the National Institute for Health Care Reform (NIHCR) and conducted by Mathematica Policy Research under the direction of the Center for Studying Health System Change. The AHCS sample included current and retired nonelderly autoworkers and their spouses who have health insurance through General Motors, Chrysler, Ford or the UAW Retiree Medical Benefits Trust. The sample was stratified by worker type (active vs. early retiree), and active workers were further stratified by auto company and whether the respondent was enrolled in a health maintenance organization or another type of plan. The survey was administered primarily by mail, with telephone follow up in cases where sampled individuals did not complete and return the questionnaire. Surveys were mailed to respondents between July 2012 and February 2013. The sample size was 8,636, and the overall response rate for the survey was 64.2 percent. Population weights were developed to produce estimates representing the entire population of workers, early retirees and their spouses. The weights were adjusted for nonresponse and were calculated separately for four subpopulations: active workers of Chrysler, Ford, and GM, respectively, and all early retirees. This was done because the variables available to adjust for nonresponse varied across the subpopulations and because the determinants of nonresponse also were likely to vary.

Back to Top

Funding Acknowledgement

This Research Brief was funded by the National Institute for Health Care Reform. The Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan organization established by the International Union, UAW; Chrysler Group LLC; Ford Motor Company; and General Motors. The Institute contracts with the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) to conduct health policy research and analyses to improve the organization, financing and delivery of health care in the United States.