Historically, collective bargaining has led to comprehensive health benefits with a broad choice of providers, modest enrollee premium contributions and limited patient cost sharing at the point of service. With rising health care costs crowding out wage increases, some labor unions are pursuing measures to slow health care spending growth without increasing workers’ out-of-pocket costs, according to a study by researchers at the former Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC).

Examples of union cost-saving strategies include reducing unit prices by negotiating volume discounts or limiting provider networks; attempting to reduce utilization through improved care coordination, especially for patients with multiple, complex chronic conditions; and using wellness programs aimed at improving workers’ health and controlling longer-term costs. In general, factors that appear to foster innovation in collectively bargained health benefits include purchasers with a concentrated volume of workers in a particular market exercising leverage to obtain discounts; direct provider contracting that sidesteps health-plan intermediaries; and financing arrangements where unions bear some responsibility or control over health benefits—for example, plans operated under Taft-Hartley trusts or joint labor-management coalitions.

- Health Costs Crowd Out Raises

- How Collective Bargaining Shapes Health Benefits

- Cost-Saving Strategies

- Reducing Unit Prices

- Promoting Efficient Care Delivery

- Wellness Programs

- Factors Affecting Innovation

- Key Takeaways

- Notes

- Data Source

Health Costs Crowd Out Raises

Employer-sponsored health insurance covers nearly 60 percent of all Americans, or about 190 million people.1 Most Americans with employer coverage have little influence on the design of their health benefits because those decisions rest solely with their employers. Some Americans have health benefits that are collectively bargained by employers and labor unions but typically provided through health plans administered by the employer. In some cases, unionized workers are covered through Taft-Hartley trusts that are jointly governed by management and labor representatives—collective bargaining in this type of plan focuses only on the size of the employer’s financial contribution for health benefits. In both cases, health benefits are included in contract negotiations along with wages and other benefits.

Compared to nonunionized workers, unionized workers tend to have more comprehensive health benefits, contribute less to premiums and face lower patient cost sharing. For example, the average annual deductible for workers in firms with at least some unionized workers is about half that of workers in firms without any unionized workers.2

Over the last decade, employers not subject to collective bargaining have responded to rising health insurance premiums by shifting costs to workers through increased premium contributions, greater patient cost sharing in the form of higher deductibles, coinsurance and copayments, and reduced benefits. For the most part, unions have resisted efforts to shift costs or reduce workers’ health benefits. In recent years, many union contract disputes have centered on health benefits—one example is the 2013 strike by San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit workers represented by the Amalgamated Transit Union and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). However, amid growing awareness that ever-rising health spending crowds out wage increases and other compensation, some union leaders are embracing efforts to slow health care spending growth without shifting costs to workers.

In an attempt to better understand how innovative health benefit strategies come about in a collective bargaining environment, this analysis examines activities in eight health benefit plans covering unionized workers (see Data Source). The analysis also examines challenges to adopting cost-containment strategies and identifies implications for purchasers.

Back to Top

How Collective Bargaining Shapes Health Benefits

While the influence of collective bargaining on health coverage takes different forms, there are generally three common approaches to financing and administering health benefits subject to collective bargaining:3

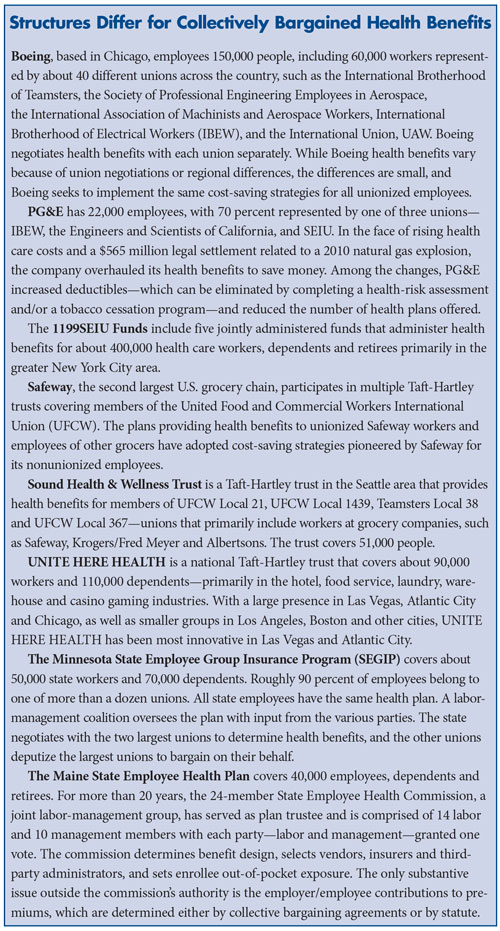

- A public or private employer finances and administers health benefits under terms agreed to by management and union negotiators and ratified by union members. Two employers in this study follow this model: Boeing and Pacific Gas & Electric Co. (PG&E).

- Multiple employers and unions—often in a related industry, such as construction—establish a Taft-Hartley multiemployer health and welfare plan governed by a board of trustees with equal employer and union representation. In most Taft-Hartley trusts, unions bargain with employers for a fixed amount per hour worked that is contributed to the trust to provide health benefits for covered workers. The Taft-Hartley plans included in the study are the 1199SEIU Funds, UNITE HERE HEALTH, Sound Health & Wellness Trust, and multiple Taft-Hartley trusts covering Safeway’s unionized workers.

- A public employer and one or more unions form a joint labor-management coalition that is responsible for collaboratively negotiating and administering health benefits for all employees—both labor and management. Two joint labor-management coalitions are included in the study: the Minnesota State Employee Group Insurance Plan (SEGIP) and the Maine State Employee Health Commission (see box below for a more about the health benefit plans in the study).

Back to Top

Cost-Saving Strategies

To reduce health care costs, the health benefit plans in this study adopted three main types of innovations:

- Strategies to reduce the unit prices of health care services or prescription drugs.

- Strategies to promote more efficient delivery of care by reducing spending through lower utilization of services.

- Strategies to reduce longer-term utilization and costs through wellness programs focused on improving workers’ health.

Back to Top

Reducing Unit Prices

Growing evidence shows that prices for health care services vary widely both across and within local markets.4 Some providers have gained significant market power to command high prices from private purchasers for a variety of reasons, including consolidation, providing unique services and sometimes reputations for superior clinical quality. Broadly speaking, one way to combat provider market power is to leverage patient volume against high-price providers. Collectively bargained plans in this study have adopted three tactics—negotiating volume discounts, reference pricing and limited-provider networks—that seek to do just that.

Negotiating volume discounts. This approach, which essentially uses patient volume as a lever to get lower prices from providers, is particularly suited for prescription drugs and radiology and laboratory services. For example, the 1199SEIU Funds approached pharmaceutical companies and requested price breaks for drugs—one example is Lipitor, where the union plan obtained substantial discounts before a generic was available—in exchange for designation as the preferred drug in a therapeutic class with a zero copayment. The1199SEIU Funds started with 15 drug classes and now include 80 drug classes, covering about 65 percent of the funds’ total prescription drug spending. Because the 199SEIU Funds cover many people and have structured health benefits to offer significant incentives for enrollees to choose the preferred drug, pharmaceutical companies can gain substantial market share by gaining preferred status.

The 1199 SEIU Funds follow a similar strategy with provider networks. Using direct contracting, the funds, for example, competitively bid all laboratory and radiology provider contracts. After switching between multiple laboratory providers over the course of a few years, the funds were able to get two major lab providers to agree to the same pricing without requiring exclusivity, resulting in a 35 percent price reduction for laboratory services. The funds also steered radiology services to one preferred vendor for a 28 percent discount.

Negotiating volume discounts for pharmaceuticals, lab services and radiology services fits well with the funds’ philosophy of maintaining generous health benefits with no or very low patient cost sharing. Respondents noted that some patients initially faced minor inconveniences for lab work because some, for example, could no longer “go down the hall from the doctor’s office.” In a relatively short time, other lab providers reduced their prices for 1199SEIU patients to retain their business. Patients reportedly did not have to travel very far for radiology services because there were enough providers within a reasonable distance. In fact, respondents suggested that the population density of the New York City area was important to the success of negotiating volume discounts because there were ample lab and radiology providers in a concentrated geographic area—one implication is that the strategy might be less effective elsewhere.

Reference pricing. Another approach to lowering unit prices is reference pricing, where a purchaser sets a maximum allowed payment amount—the reference price—for a specific drug or medical service. If enrollees receive care at a provider with an allowed amount greater than the reference price, the enrollee must pay the additional amount out of pocket. Part of reference pricing’s appeal to purchasers is that the approach maintains wide choice of providers. The enrollee decides whether to be treated at a lower-price provider with no out-of-pocket expense beyond typical cost sharing or a higher-price provider with additional cost above the reference price.

Safeway initially used reference pricing for prescription drugs for nonunionized workers, and the practice is now used in several Taft-Hartley plans that cover grocery workers at both Safeway and competing grocery stores. The Taft-Hartley plans have worked with Safeway Health, an independent consulting firm founded by Safeway, to implement reference pricing programs for prescription drugs.

Working with the plans’ pharmacy benefits manager, Safeway Health’s program identifies prescription drugs with less-costly therapeutic equivalents—drugs with similar effects but a different chemical make-up in more than 65 therapeutic categories. Safeway Health set the reference price at the level of the least-costly therapeutically equivalent drug. If enrollees opt for the more expensive drug, they pay the difference between the reference price and the more expensive drug. If an enrollee’s physician believes the less-costly drug is inappropriate, the patient can request an exemption, and if granted, obtain the more expensive drug without additional cost. An internal Safeway Health assessment compared the six months before and after the program was implemented in August 2012 for 273,000 enrollees, estimating that reference pricing led to a 21 percent spending reduction. When faced with switching to the lower-cost alternative or paying out of pocket, 91 percent of enrollees switched, 1 percent requested and received an exemption, and 8 percent continued with the more expensive drug, paying the difference out of pocket.

In a similar approach, the 1199SEIU Funds initially implemented a preferred drug list and mandatory generic drug program. At the time, preferred and generic drugs had a zero copayment, while the copayment for non-preferred drugs was $16. The preferred drug list and mandatory generics programs evolved into a reference pricing system, where preferred drugs and generics have no patient cost sharing. However, instead of a $16 copayment for non-preferred drugs, enrollees pay the full cost of the non-preferred drug beyond the price of the preferred drug. The same rules apply for brand-name drugs when generics are available.

Relative to other strategies, respondents did not report much resistance to reference pricing on the part of union leaders or rank-and-file members. Indeed, the 1199SEIU Funds adopted reference pricing as a cost-saving strategy because it fits with the funds’ overall philosophy that workers should have access to health care with minimal out-of-pocket costs. As one fund trustee said, “We wanted to use collective strength and talent to figure out what we could do to give members options and choices, that if they followed certain rules, they could still get ‘free’ health care, and if they didn’t pick those choices, there would be costs to them.”

Limited-provider networks. Emerging payer strategies to counter provider pricing power include developing limited-provider networks that either exclude high-price providers or require greater patient cost sharing to use non-preferred, in-network providers.

Narrow-network plans exclude certain—usually high-cost and/or low-quality—providers with a goal of minimizing spending and improving quality. In 1998, UNITE HERE HEALTH created the Health Care Services Purchasing Coalition in Las Vegas. Now known as the Health Services Coalition, the group covers about 280,000 people and includes representatives of UNITE HERE HEALTH and other area union trusts, public employers and gaming industry self-insured plans. The Health Services Coalition negotiates direct contracts with Las Vegas hospitals for its members. These contracts have consistently achieved lower rates than were otherwise available to self-funded groups in the Las Vegas market. In Las Vegas, UNITE HERE HEALTH—known locally as the Culinary Health Fund—leads direct contracting for hospital services on behalf of the coalition and either directly contracts or enters into unique network arrangements for other health services. It does this in place of using an insurer or managed care organization. These arrangements allow UNITE HERE HEALTH to collect comprehensive claims data to monitor cost and quality indicators.

In 2002-03, UNITE HERE HEALTH eliminated 50 physician practices it identified as higher cost and lower quality. At the same time, it retained a relatively large network of about 1,800 physicians. While reducing the network by less than 3 percent may not seem like a drastic change, the move reportedly generated considerable savings, making it possible to give two annual raises of 60 cents to 65 cents per hour—and smaller raises in at least two subsequent years—to 50,000 workers whose average wage at the time was $13 an hour. The increased scrutiny sent a signal to the remaining physicians that their practices were being observed, providing motivation to improve their performance.

However, limiting enrollees’ access to providers can generate a backlash, according to respondents. This was an especially big challenge for the coalition when some enrollees’ physicians were dropped from the network. In fact, union members picketed coalition offices when 100 doctors initially were slated to be dropped from the network. As a compromise, 50 doctors were kept in the network, because they offered hard-to-find services, spoke a necessary language or were favored by a large number of coalition members.

In contrast to narrow networks that exclude certain providers, tiered-provider networks use quality and efficiency metrics to assign providers to cost-sharing tiers, with the goal of directing patients toward more cost-effective providers through financial incentives. Another goal is to incentivize providers in non-preferred tiers to reduce prices or improve quality in exchange for preferred status.

Both the Maine State Employee Health Commission and the Minnesota State Employee Group Insurance Program also developed tiered-provider networks but later expanded the approach to address utilization issues as well as high unit prices.

Back to Top

Promoting Efficient Care Delivery

Narrow- and tiered-provider networks can lead to cost savings by steering patients toward lower-price providers and by encouraging non-preferred providers to reduce prices to retain patients. However, these approaches largely rely on fee-for-service payment that can encourage unnecessary care. Recognizing this issue, several collectively bargained health benefit plans in the study adopted provider payment reforms, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), that move away from fee-for-service payment and reward more efficient care delivery and potentially reduce utilization.

ACOs on a tiered-network platform. ACOs are groups of providers that accept responsibility for the cost and quality of care for a defined group of patients. The theory behind ACOs is to encourage providers to work together to improve quality and reduce costs by creating a global budget for a patient population and sharing savings and/or risk with providers. The Maine State Employee Health Plan and the Minnesota SEGIP both adopted ACO-like programs following creation of their tiered-provider networks.

The Maine State Employee Health Commission initiated a tiered-hospital network in 2006 with a goal of both improving hospital quality and controlling costs. Initially, 14 of the 36 acute care hospitals in the state met quality criteria to be placed on the preferred tier. At first, enrollees had a small financial incentive to use preferred providers—a $200 deductible for non-preferred hospitals and no deductible for preferred hospitals. Over time, the cost-sharing differential increased to $500 for preferred hospitals and $2,000 for non-preferred hospitals.

As financial incentives became more significant and potentially impacted market share, non-preferred hospitals, including MaineGeneral Medical Center, which serves many state employees because of its location in the state capital, sought other ways to work with the state. Since 2011, MaineGeneral has had an ACO pilot program that ties financial risk to performance measures related to access, quality, safety and patient experience, as well as achieving per capita cost targets. In exchange for participating in the ACO pilot, MaineGeneral’s patients who are enrolled in the state employee plan do not face additional cost sharing. Two other major health systems—Beacon Health and MaineHealth—have entered into ACO pilots with the commission. Nearly 90 percent of state employee plan members are now covered under ACO risk-based contracts.

In 2002, the Minnesota SEGIP implemented the Minnesota Health Advantage Plan, which tiers providers based on efficiency and reduces patient cost sharing if enrollees use lower-cost providers. Also in 2002, SEGIP required members to select a primary care practice, which is accountable for the total cost of care, including referrals to other services and hospital admissions. Primary care centers that do not manage costs effectively lose their preferential rating, which drives members toward other providers.

High-intensity primary care/ambulatory intensive care units. High-intensity primary care programs—also sometimes referred to as ambulatory intensive care units, or AICUs—are similar to patient-centered medical homes but focus on the sickest, highest cost chronically ill patients. Through increased care coordination and improved self-care, the goal is to reduce costly emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

Boeing, UNITE HERE HEALTH, and Sound Health & Wellness each established high-intensity primary care programs. To encourage participation, purchasers waived some or all patient cost sharing, particularly for primary care and maintenance medications for chronic conditions.

Respondents noted that getting unions on board with high-intensity primary care programs was relatively easy because they are perceived as an added benefit rather than a take-away or a discriminatory practice—in contrast to wellness programs/health coaching, which many unions view as too intrusive. For example, according to Boeing, unions were very supportive of the high-intensity primary care program, viewing the program as a way to both improve care and manage costs. Reportedly, the Boeing program was established informally rather than through collective bargaining. According to respondents, while union leaders generally supported the Boeing primary care program, it was challenging to recruit patients to enroll.

Back to Top

Wellness Programs

Another common approach in collectively bargained health benefit plans is the adoption of wellness programs designed to improve workers’ health and reduce health care utilization in the longer run. In general, wellness programs include financial incentives to encourage activities like completing a health screening or health risk assessment (HRA), taking smoking-cessation classes, or joining a gym. Financial incentives include gift cards, premium reductions, reduced deductibles or higher contributions to health reimbursement accounts. Some plans include small rewards for healthy behaviors as a first step and then shift to penalties for nonparticipation.

Since 2004, Boeing has used financial incentives to encourage all employees to complete health risk assessments and, more recently, onsite health screenings. The company initially offered $25, and then $50, gift cards to employees completing a health risk assessment. But several years ago, Boeing began charging an extra $20 monthly health insurance premium to employees not completing an HRA. The shift was designed to encourage employees to take more responsibility for their wellbeing and increase participation. Indeed, according to respondents, this change increased participation rates for Boeing’s unionized workers from about 40 percent with the $50 gift cards to about 85 percent with the premium surcharges.

Boeing also offers health coaching to employees identified through HRAs and onsite screenings, and the company encourages voluntary participation in a physical activity program and offers $50 or $100 gift cards to reach certain activity levels.

PG&E has completely redesigned its health benefit offerings, shifting solely to offering health plans with a $1,000 deductible for individuals and a $2,000 deductible for families, as well as moving from copayments to coinsurance and increased out-of-pocket maximums. PG&E and union leaders worked collaboratively on the benefit redesign, which includes options for enrollees to undergo biometric screening and tobacco cessation counseling to reduce their deductible to zero.

Similarly, Sound Health & Wellness has moved away from very comprehensive benefits with minimal patient cost sharing by offering plans with higher deductibles of $250 or $350 paired with a health reimbursement account, out-of-pocket maximums of $2,250 or $2,750, and coinsurance of 85 percent or 80 percent, depending on workers’ tenure. While workers’ premium contributions remain modest—less than $100 a month—the trust has worked to control costs by introducing deductibles tied to health reimbursement account contributions for participation in wellness programs. Plan members can earn $500 in health reimbursement account contributions through trust-approved preventive and wellness activities, such as identifying a primary care provider, updating contact information, taking a personal health assessment and a variety of wellness activities, including getting a flu shot or colonoscopy or participating in health coaching.

While several union health benefit plans have adopted wellness programs in addition to Sound Health & Wellness, respondents identified some resistance from union leaders and rank-and-file members concerned about the privacy of health screenings and health risk assessments and possible repercussions, such as workers losing jobs for having costly conditions. In response, plan administrators took steps to make clear that third-party vendors conduct the screenings and assessments and that personally identifiable information would not be disclosed. Respondents reported these measures helped allay some concerns and increased workers’ willingness to participate but noted some were still suspicious or concerned that the company would access their personal health information.

According to respondents, unions also dislike programs that create differential treatment of union members—for example, by charging a penalty for not participating in wellness programs—and instead are less averse to completely voluntary wellness programs that offer rewards for participation. Unions also perceive certain aspects of wellness programs to be intrusive—for example, health coaching programs where health screenings identify workers with diabetes or other chronic conditions and have health coaches call workers to engage them in a treatment plan.

Back to Top

Factors Affecting Innovation

Several factors appear to influence which innovations collectively bargained plans pursue, including the type of collectively bargained plan, the degree of market leverage, and the organizational culture of the employer and the union.

Type of collectively bargained health benefits. Taft-Hartley trusts appear to be more inclined to innovate than other collectively bargained plans. Because Taft-Hartley plans include multiple employers, they tend to be larger, giving them a stronger negotiating position when purchasing services and reducing per-enrollee administrative costs. Since they are created solely to provide health and other benefits, Taft-Hartley trusts also have professional and specialized staffs to help develop and implement cost-saving strategies.

The working relationship among Taft-Hartley trustees tends to be less adversarial than other labor-management relationships because labor and management have already negotiated the amount of money designated for health benefits. With the amount of money for health benefits already set, union leaders are more likely to view money used inefficiently as wasted and thus may be more amenable to cost-saving innovations. One respondent explained that Taft-Hartley plans’ shared governance encourages compromise, saying, “Since neither side can dictate to each other—if everybody involved approaches it right—the structure forces both sides to look for better ways to save money rather than simply offloading costs to employees or cutting benefits.” Additionally, Taft-Hartley plans may be more sensitive to long-term costs and pursue strategies that require more initial investment but offer more potential long-term cost savings.

Size or market leverage. A large concentration of workers in a geographic area gives purchasers more leverage over providers and the patient volume necessary for certain innovations. As a Taft-Hartley plan representative explained, “When you are negotiating rates with a [provider], their tipping point is volume. If there is no volume, [they think], ‘Why should I even be involved with this plan?’ The fact that we can bring [a large number of] lives in a concentrated area [makes] these [providers] want to see our members.” And strategies that steer members toward efficient providers or lower-price services could not work without this leverage.

Large volume also enables purchasers to contract directly with providers rather than using health insurers or third-party administrators. For instance, direct contracting was critical for UNITE HERE HEALTH to narrow its physician network in Las Vegas using claims data unavailable to many purchasers. In areas where UNITE HERE HEALTH does not contract directly with providers, health plans sometimes resist providing data, hindering innovation. The 1199SEIU Funds directly contract with about 20,000 physicians and 75 hospitals, and a respondent noted, “On the hospital side we can decide to pay on DRG [diagnosis-related group] or pay on a per diem. We can control the methodology and get the best deal. With an insurer [they pay] whatever they think is the best—which may not benefit the plan. [The] same thing [occurs] with labs and radiology.”

Employer and union culture. The culture of the employers and unions plays a role in pursuing cost-saving strategies. Some health benefit plans adopted high-deductible plans tied to wellness programs because they believed motivating employees to take responsibility for their health will lead to improved health, productivity and long-term savings. In contrast, the 1199SEIU Funds primarily cover lower-income health care workers and are committed to removing cost barriers to care, leading to greater willingness to adopt strategies that steer patients to lower-price providers while minimizing patient cost sharing.

Back to Top

Key Takeaways

Among the common themes that emerged from interviews with experts on union health benefits and innovative cost-control strategies, the following stand out:

- No single factor drives the type of cost-saving strategy a union health plan pursues. Respondents noted factors as varied as collective bargaining structure, geography, size, local market trends, leadership and organizational culture as important to why they decided to pursue particular innovations. An organization attempting a one-size-fits-all approach to reducing health care costs or simply replicating what another organization has done without tweaking it to fit its unique circumstances is unlikely to succeed.

- A good management-labor working relationship makes it much easier to pursue cost-saving strategies. Taft-Hartley trusts avoid some of the adversarial nature of collective bargaining by separating the responsibilities of bargaining for the financing of health benefits and the actual design of health benefits. Joint labor-management committees, or just frequent communication between union and management leaders, help build trust and let both sides work through problems before presenting their ideas to the broader union membership for ratification.

- Directly raising members’ premium or out-of-pocket costs is difficult. The collectively bargained health benefit plans that increased premium contributions or patient cost sharing were only able to do so in conjunction with ways for members to decrease or eliminate added costs, for example, by participating in wellness activities. While most union leaders understand the need to reduce health care spending, simply shifting costs is viewed unfavorably by union members.

- Sometimes all it takes is one person to drive innovation. Multiple respondents noted particular innovations that mainly came about as the result of the work of a single person.

Back to Top

Notes

| 1. | Fronstin, Paul, Sources of Health Insurance and Characteristics of the Uninsured: Analysis of the March 2013 Current Population Survey, Issue Brief No. 390, Employee Benefit Research Institute, Washington, D.C. (September 2013). |

| 2. | Kaiser Family Foundation, Menlo Park, Calif., and Health Research & Educational Trust, Chicago, Ill., Employer Health Benefits 2013 Annual Survey (August 2013). |

| 3. | This study included health plans for unionized workers where health benefits were either subject to collective bargaining agreements or union leaders were involved in developing a cost-saving strategy. For example, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) was excluded. Although CalPERS has pursued a number of innovative cost-saving strategies, CalPERS’ health benefits are not subject to collective bargaining—only the dollar amount of workers’ premium contributions falls within the scope of collective bargaining agreements. |

| 4. | White, Chapin, Amelia M. Bond and James D. Reschovsky, High and Varying Prices for Privately Insured Patients Underscore Hospital Market Power, HSC Research Brief No. 27, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (September 2013). |

Back to Top

Data Source

This Research Brief is based on 22 interviews with market observers, health benefits consultants, employer coalitions, directors of Taft-Hartley trusts and union leaders. Interviews were conducted by two-person research teams between January and September 2013, and notes were transcribed and jointly reviewed for quality and validation purposes. The eight union health plans in the study were identified through interviews with vantage respondents—individuals with expertise on collectively bargained health plans and health benefit innovation.