Although U.S. health care spending growth has slowed in recent years, health spending continues to outpace growth of the overall economy and workers’ wages. There are clear signs that rising prices paid to medical providers—especially for hospital care—play a significant role in rising premiums for privately insured people. Over the last decade, some hospitals and systems have gained significant negotiating clout with private insurers. These so-called “must-have” hospitals can and do demand payment rate increases well in excess of growth in their cost of doing business. During the 1970s and ’80s, some states used rate-setting systems to constrain hospital prices. Two states—Maryland and West Virginia—continue to regulate hospital rates. State policy makers considering rate setting as an option to help constrain health care spending growth face a number of design choices, including which payers to include, which services to include, and how to set payment rates or regulate payment methods. To succeed, an authority charged with regulating rates will need a governance structure that helps insulate regulators from inevitable political pressures. Policy makers also will need to consider how a rate-setting system can accommodate broader payment reforms that promote efficiency and improve quality of care, such as episode bundling and rewards for quality.

- Negotiating Power Shifts to Hospitals

- Hospital Price Growth

- History of Rate Setting

- Key Design Questions

- Challenges to Rate Setting

Negotiating Power Shifts to Hospitals

Under pressure from rapidly rising health care costs, employers in the late-1980s and early 1990s began shifting workers into managed care products—primarily health maintenance organizations (HMOs)—with restrictive provider networks and tighter utilization management. Promising increased patient volume, health insurers also pushed hospitals and physicians to accept lower payment rates. At about the same time, hospitals began a wave of mergers and acquisitions to cut costs, eliminate excess capacity and strengthen their negotiating clout with private insurers.

Amid the backlash against tightly managed care in the mid-1990s and the economic boom of the late-1990s, the balance of negotiating power shifted markedly from insurers to providers, especially hospitals. As the economy improved, employers became less concerned with controlling costs and more concerned with attracting and retaining workers. Employers gravitated away from HMOs toward health insurance products with a broad choice of providers—typically preferred provider organizations (PPOs)—to quell worker discontent with restrictions on provider choice. To market attractive PPO and other insurance products, health plans created large, inclusive provider networks. Lacking a credible threat of excluding providers from their networks, health plans lost significant negotiating leverage.

Provider demands for higher payment rates and other favorable contract terms led to a rash of plan-provider contract showdowns in the early 2000s, when many providers threatened and some actually dropped out of health plan provider networks.1 When the economy slowed again and health care spending growth accelerated rapidly, instead of limiting provider choice, employers began shifting costs to workers through increased patient cost sharing—higher deductibles, coinsurance and copayments.

Hospital Price Growth

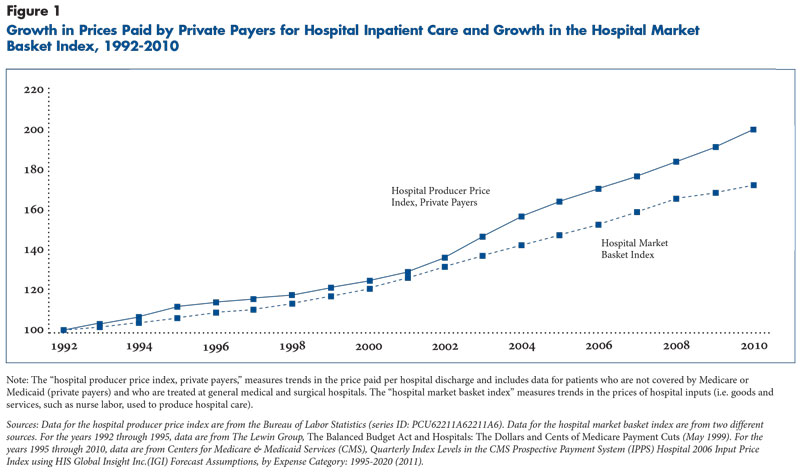

In 2000, hospital prices paid by private insurers on average exceeded hospitals’ costs by 16 percent—by 2009, that gap had grown to 34 percent (see Figure 1).2 However, a growing body of research shows hospital prices vary widely both within and across communities.3 Along with market concentration, other factors—for example, hospital reputation, provision of unique specialized services and dominance in geographic submarkets—appear to play a role in the importance that consumers place on hospitals’ inclusion in health plan networks and the prices that hospitals are able to command. Even in markets with dominant insurers, health plans appear unable or unwilling to constrain hospital price increases, because they can pass along higher costs to employers.

Price-variation analyses consistently point to differences in hospital market power as the central explanation rather than differences in hospital quality or patient complexity.4 Elements of health reform that encourage greater integration of hospitals, physicians and other providers—for example, accountable care organizations—likely will encourage more consolidation and potentially increase hospitals’ negotiating leverage.

Two broad options are available to address rapidly rising hospital prices—market forces and regulation. The prevailing market approach involves adopting insurance products that motivate enrollees to consider price. Examples include narrow-network products, which exclude higher-cost providers, and tiered-network products, which place higher-cost providers in tiers requiring higher patient cost sharing at the point of service. The alternative to market forces is hospital rate setting by a public entity. Rate setting could take relatively loose forms, such as a limit based on some multiple of Medicare payment rates, or could be highly structured, such as the system used in Maryland since the 1970s.

This analysis describes key design options that state policy makers would need to consider in developing a rate-setting system, including which payers to include, which services to include, and how to set payment rates or regulate payment methods.

History of Rate Setting

Hospital rate setting, as practiced in the 1970s and 1980s, sought mainly to correct the inherent flaws of the then-dominant hospital payment method—cost reimbursement. Akin to giving providers a blank check, cost reimbursement provided no incentives for hospitals to operate efficiently. Many states considered multi-payer hospital rate setting, and eight eventually enacted laws authorizing public agencies to regulate hospital rates.5 Approaches varied from state to state, but regulators generally focused on constraining inpatient per-diem or per-case payment rates in an attempt to control hospital costs. Responding to regulators’ focus on controlling rates, hospitals in some states provided more units of service, weakening the overall constraints on spending growth.6

Studies show strong and consistent evidence that rate setting slowed aggregate total hospital spending in New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey and Washington.7 The exception was Connecticut, where regulators reportedly lacked the authority to enforce payer and hospital compliance with approved rates.8 Rate-setting studies also found neither adverse nor positive effects on regulated hospitals’ financial status.9 West Virginia’s regulation of hospital rates did not begin until 1985, and enabling legislation took the form of a rate freeze and initially was limited to mandatory budget reviews.10 Given its later adoption, West Virginia’s regulatory experiences have not been included in evaluations of rate-setting systems and have received little attention from researchers and policy makers.

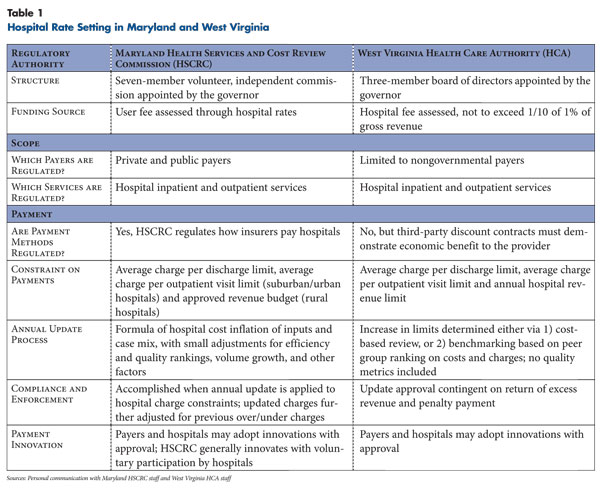

Despite success in containing costs, hospital rate setting was abandoned by all states except Maryland and West Virginia (see box and Table 1 for more about both states’ rate-setting systems). Rate regulation’s fall from favor by the early 1980s has been attributed to:

- implementation of the Medicare inpatient prospective payment system, which provided strong incentives for hospitals to increase efficiency;

- the larger national shift toward deregulation of industry generally; and

- excessive complexity in rate-setting formulas, which confused even major stakeholders and raised suspicions of gaming.11

Moreover, with the entrance of HMOs into markets and later growth of PPOs, private payers often viewed rate setting as an obstacle to negotiating more-substantial discounts in an unregulated market.

In the two states where rate setting survives, hospital cost containment has continued. The Maryland Health Services and Cost Review Commission (HSCRC) calculated cumulative savings between 1976 and 2007 of $40 billion attributable to the state’s rate-setting system.12 In practice, Maryland has not always been effective in controlling costs. Hospital costs rose more rapidly than the national average for about five years after 1992,13 and admission rates escalated between 2001 and 2007,14 both reportedly as a result of policy changes that were later reversed.15 The same is true for West Virginia. Costs increased at a faster rate in West Virginia than in the nation as a whole from 1985, when mandatory hospital budget review was implemented, until 1992, when the law was amended to use actual hospital costs as the basis of rate updates rather than setting limits based on hospital revenue.16 After that, costs increased at a slower rate than the nation.17 The implication from experiences in both Maryland and West Virginia is that cost savings generated by rate setting are possible but will depend on the specific policies implemented.

Last States Standing—Hospital Rate Setting in Maryland and West Virginia

Maryland. The state established the Health Services and Cost Review Commission (HSCRC) in 1976 to regulate hospital rates for all payers. The state received a waiver to include Medicare, and the state Medicaid agency delegated authority to set Medicaid rates to the HSCRC. Commissioners are appointed by the governor, and the seven-member independent commission is funded by a fee assessed on hospitals. The commission’s decisions are not reviewable by the legislative or executive branches.

All hospitals must bill and all payers must pay based on a list of approved payment rates for service-specific and departmental units—for example, the operating room charge per minute or intensive care unit charge per day. The aggregate payments to urban hospitals are capped by an average per case rate based on All Patient Refined-Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs), a system that classifies patients based on clinically similar condition groups, severity of illness and risk of mortality, which all reflect an expected level of resource use. Approved rates also are set for outpatient visits in the same manner. Alone, this would not constrain volume, so volume that exceeds the baseline year is reimbursed at 85 percent of the approved case rate. Hospitals return the other 15 percent through an aggregate downward adjustment to the following year’s rate.

Rural hospitals are constrained by a cap on total annual revenue. Annual updates to unit-of-service rates and revenue constraints are based on a formula that accounts for hospital cost inflation and case mix, with small adjustments for efficiency and quality rankings, and other factors. The HSCRC provides two means for payment innovation. Hospitals may seek approval to contract with payers using an innovative arrangement. And, HSCRC may propose voluntary payment innovations to hospitals.

West Virginia. The state established a hospital rate-setting system in 1983. The state’s regulatory authority rests with the West Virginia Health Care Authority (HCA), an autonomous division within the state Department of Health and Human Resources and funded by a hospital assessment that cannot exceed one-tenth of 1 percent of gross hospital revenues. Rate-setting authority extends only to nongovernmental payers because the state lacks a waiver from Medicare and HCA was not authorized to regulate Medicaid payments. Initially, each hospital’s total revenue from nongovernmental payers was frozen, and then the HCA established a budget review process in 1985. Actual hospital costs were factored into the annual review process for the first time in 1993.

A benchmarking process was legislated in 1999, which limited the rate increases a hospital could receive without review based on its ranking against peer hospitals on costs and charges. This updating formula accounts for cost inflation and is comparable to Maryland’s formula but omits quality metrics. Hospitals may accept the guaranteed rate increase set through the benchmarking methodology or apply for a higher rate increase subject to a lengthy review.

There are no restrictions on payment methods, but all contract language is subject to review, and payment below cost is prohibited. For each hospital, the HCA also sets annual revenue limits, sets limits on the average charge per discharge and requires approval of new services. Excess revenue must be returned before the next year’s update is approved, and the burden of proof remains with the hospital in disputes with the authority, so HCA reported no problems with hospital compliance.

Key Design Questions

State policy makers contemplating the design of a new rate-setting system will face key design questions, including:

- Should rate setting be limited to private insurers or also include Medicaid and Medicare?

- Should rate setting apply only to inpatient hospital care or should outpatient and physician services be regulated as well?

- Which entity should assume rate-setting authority, and how should it be funded?

- How should payment rates be set, should a unit of payment be specified, and should constraints be placed on hospital revenue or discharge volume?

- How can rate setting support payment innovations?

Scope of Rate Setting

The scope of a rate-setting system refers both to the range of payers and the range of medical services regulated.

Which payers? Any rate-setting system would presumably include private insurers, because they pay the highest prices on average, and many would perceive an opportunity for protection from hospitals with extensive leverage. Even so, each private payer would benefit differentially from rate setting, since the rates they now pay vary considerably. Private insurers with large market shares—for example, many Blue Cross Blue Shield plans—might lose a competitive advantage if their rates were equalized with other insurers.18

A design challenge for policy makers is whether to include Medicare and Medicaid. Including Medicare and Medicaid would have the advantage of sending hospitals consistent signals from all payers by having the same payment methods and similar degree of constraint apply. But, Medicare participation in a state rate-setting system would require a federal waiver that would be granted only if participation did not increase federal costs.19 This could be a major stumbling block, because Medicare hospital prices on average are much lower than private insurer rates. Increasing Medicare prices to equal private insurer prices would be incompatible with a waiver, while decreasing private insurer prices to match Medicare could damage hospitals’ financial viability. A rate-setting system could, however, grandfather existing differentials between Medicare and private insurer rates without increasing Medicare spending. This approach also would be needed for Medicaid, where rates tend to be substantially lower than Medicare rates. But, governors might be reluctant to cede control over Medicaid rates to an independent rate-setting entity.

If folding Medicare into a state rate-setting system is unfeasible, Medicare’s existing payment system could serve as a benchmark for setting payment rates for private payers. Private payer rates initially could be set at some multiple of Medicare rates, and Medicaid rates could be set at some fraction, but all rates could be benchmarked off of Medicare.

Which services? In addition to providing inpatient services, hospitals provide a range of other services, including outpatient, home health and skilled nursing care. One key decision in designing a hospital rate-setting system is choosing which services to include. The most basic approach would be to regulate only prices for inpatient services, but other payment reforms, such as bundled payments for episodes of care, already draw in multiple providers and services, so regulatory authority would need to be broad enough in scope to accommodate these payment approaches. Both Maryland and West Virginia place constraints on payment to hospitals for outpatient visits, but neither regulates payment for physician services.

Governance

Key design considerations in governance include placement of the regulatory authority within state government, financing and membership.

Placement within government. The authority to regulate hospital rates could be assigned to an executive-branch state agency or to an independent commission. Assigning authority within the executive branch could allow for coordination with other executive-branch initiatives, but an independent commission would more likely support autonomous decision making and be perceived as a neutral forum by stakeholders.

States could grant rate-setting authority to state health insurance exchanges. Exchanges will already have broad authority under the national health reform law—the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—to set standards for health plan participation in the exchanges, and they will have a strong interest in offering affordable coverage. The relatively small share of privately insured people expected to get coverage through exchanges would limit impact on total spending in the near term but might elicit less provider resistance. Moreover, adding a rate-setting component to the rules of engagement could promote plan competition in exchanges, enticing otherwise disadvantaged insurers to participate by lowering entry barriers.

Funding source. How the regulatory authority is funded can influence its independence. Annual appropriations may leave funding vulnerable to lobbying pressures from stakeholders. Dedicated funding, such as fees charged to providers and/or insurers, would be less susceptible to political pressure. Both Maryland and West Virginia rely on dedicated, fee-based funding.

Membership. Membership and term length also can play a role in the independence of a regulatory entity. Until recently, gubernatorial appointments to the seven-member Maryland commission have avoided potential conflicts of interest—for example, appointment of a hospital executive—but through political tradition rather than legislative mandate.20 In contrast, West Virginia law specifies board members’ qualifications and explicitly prohibits members from regulated entities. The governor appoints a three-member board of directors to six-year terms, and the board draws on larger advisory groups for input.21

Limits on Payment Methods and Levels

A hospital rate-setting system consists of two elements: payment methods and payment rates.

Payment methods. Payment methods include designating the unit of payment and applying formula-based adjustments, such as case-mix severity, outlier payments for exceptionally costly cases and quality bonuses. Payment methods powerfully influence hospital incentives and clinical practices. In general, broader payment units—for example, paying for episodes of care rather than individual services—are desirable because they give providers the incentives and flexibility to achieve broader efficiencies.

As is the case in West Virginia, a rate-setting system can operate without any restrictions on payment methods. But there are at least two rationales for designating payment methods. First, the use of a common payment method can strengthen and synchronize the incentives for hospitals to behave in socially desirable ways. If only one payer implements a system of quality bonuses, hospitals may ignore it. If all payers adopt the same quality bonus, hospitals are likely to take notice. Second, in the same way that hospitals with negotiating clout can refuse to accept low payment rates, they also can refuse what they view as undesirable payment methods. Requiring payers to use uniform payment methods could help overcome potential hospital resistance.

Private payers use different units of payment for inpatient hospital care—including discharges, per diems and discounted line-item charges—and payers’ use of quality-based bonuses and case-mix adjustments also varies.22 If a state plans for payers to adopt a uniform payment method, the obvious candidate is Medicare’s methodology, which pays separately for each discharge with case-mix adjustment using Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRGs). Medicare’s payment methodology balances fairly strong incentives for hospitals to limit lengths of stay and contain costs with a well-developed case-mix adjustment system that protects hospitals financially when they care for sicker patients. But a rate-setting authority may not want to commit to Medicare payment methods if it wants to spur payment reforms.

Rather than require all private payers to use the same payment method, a less-restrictive approach is possible. States could establish allowable standards for payment methods, with payers allowed to innovate at the margins. For example, payers could be required to pay hospitals either on a per-discharge basis or using some more-aggregate unit, without any limitations on the use of case-mix adjustment or quality bonuses.

Payment rates. Setting hospital payment rates is the core way to constrain hospital spending. This constraint can be broad—a cap on total hospital annual revenue—or narrow—a cap on revenue per admission or outpatient visit.

Historically, Maryland’s approach for urban hospitals has been to set the payment rate per inpatient case and per outpatient visit. Total revenue is constrained by reimbursing volume that exceeds the volume of the baseline year at 85 percent of the approved case rate. Hospitals return the other 15 percent through an aggregate downward adjustment to the following year’s rate. For hospitals in relatively isolated rural areas, Maryland limits hospitals’ overall revenue, an approach that can be pursued because an area’s population can be linked to a hospital.

The payment rate or unit of constraint placed on hospitals does not have to be the same as the unit of payment used by insurers to pay hospitals. For example, in West Virginia, the discharge is the unit of constraint, while insurers may pay hospitals using various payment units, as long as payments on average do not exceed the per-discharge constraint of each hospital. That is, payments by insurers, once averaged across all patient stays or discharges, cannot exceed a set amount per discharge. Insurers might want to choose a unit of payment that allows tracking of patients’ resource use. In West Virginia, if the revenue received by the hospital exceeds the average per discharge allowed, the hospital returns the excess.

The regulatory authority also must determine the range of allowable payment rates. Payments could be capped, set between a ceiling and a floor, or required to equal a target. In West Virginia, contracts based on discounts from charges that do not provide an economic benefit to providers are prohibited by law, acting as a floor that forbids payment below a hospital’s cost. The range of payment rates could originate at the outset through differential base rates or could emerge through variable updates.

Base rate. In the first year of a rate-setting system, the allowable payment rate might need to be set separately for each hospital based either on the hospital’s historical payments plus an inflation factor or on the hospital’s historical costs plus an inflation factor and a markup. Setting the same initial payment rate to all hospitals could be financially disruptive. The Rhode Island insurance commissioner estimated that setting a uniform payment rate across hospitals would lead to widely varying impact on hospital revenue, with two of the state’s 11 hospitals facing more than a 30-percent reduction.23

Rate differentials between payers also could be negotiated for various purposes. Consideration for prompt payment by payers through a discount from the uniform payment rate might be attractive to both hospitals and payers. In Maryland, a small differential (2%) favorable to CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield and Medicaid was approved at the outset in consideration of prompt payment by these payers. Adjustments to rates also could play a role in distributing the burden of uncompensated care among payers and hospitals. In Maryland, both Medicaid and Medicare receive a 4-percent differential for their role in averting the cost of uncompensated care to the overall health system. A significant function of some early rate-setting systems was channeling additional funds to hospitals that served a larger number of uninsured patients, but most states eventually found other means of financing uncompensated care. Going forward, current mechanisms for financing uncompensated care could operate independently of rate setting or be integrated into regulated payments.

Updates. Once baseline rates are established, the regulatory authority would need a process for annual updates. Updates could be based on trends in hospital input prices—salaries, supplies and other costs. Updates also could factor in hospital peer performance. In both Maryland and West Virginia, the reasonableness of each hospital’s costs is measured against peers, meaning hospitals similar in size and location. Each hospital’s performance is then ranked relative to peer hospitals, and this ranking becomes one factor in the update formula. Hospitals that perform well relative to peers are rewarded with higher updates.24 Such a strategy encourages hospitals to compete with one another to some degree to control costs. If each hospital’s allowed payment rate were updated based only on its own costs, hospitals would have much less incentive to constrain costs.

Supporting Innovation and Quality

Promoting continued innovation in provider payment is important for the long-term performance of the health care system. Within a rate-setting system, regulators could take different stances on such innovation.

Expanded authority. States could mandate rate regulators to pursue payment innovation. This approach could be coupled with latitude for payer innovation as well, but allowing too much experimentation could lead to the wide price variation that rate setting seeks to minimize. The Maryland commission can experiment with new payment methods but typically relies on voluntary provider participation. Payers also may use alternative payment methods and negotiate payment rates below the state-set cap if the change will decrease utilization. For example, health plans and hospitals could negotiate an episode-based case rate to include physician and facility fees for a particular service plus pre- and post-hospitalization costs. A price for the inpatient stay that is lower than the state-set cap might be deemed reasonable if the overall packaged price for the case is achievable through better management on the outpatient side and payment is subject to quality or outcome metrics.25

Limited authority. States could choose to prospectively review and approve innovative payment arrangements, which is the approach West Virginia takes. However, without oversight, payers may circumvent rate setting under the guise of innovation. For example, the Massachusetts attorney general found that private insurers—in an unregulated environment—commonly paid hospitals above contracted prices through such means as signing bonuses and infrastructure payments.26 Since unit prices do not account for these payments, they can complicate regulatory oversight of rate compliance. Reporting requirements on payment innovations could help regulators assess whether payment innovations are promoting rate-setting goals or circumventing them.

Quality. State regulators also could incorporate incentives to promote quality by allowing higher rates in return for higher quality. The payment formula would need to determine the relative weight or importance of different kinds of quality metrics—for example, measures of patient outcomes, safety and satisfaction. Heavy reliance on outcome measures might increase concerns that hospitals disproportionately serving disadvantaged patients could be penalized unfairly. Yet, payers and consumers will want to pay for tangible results like fewer rehospitalizations. A rate-setting system can provide a platform to reach consensus among payers and providers on standard quality metrics and then link payment to hospital performance.

For example, the Maryland Admission-Readmission Revenue program shows the potential to integrate quality objectives into a rate-setting framework. This voluntary pilot established a warranty arrangement for 30-day readmissions for all patients, under which hospitals keep 100 percent of the savings from reducing all-cause readmissions over a three-year period but must absorb the cost of any increase in readmissions.27 Maryland’s approach provides incentives for all hospitals to reduce readmissions irrespective of their baseline rate, leaving no hospitals disadvantaged in the competition and increasing cost savings for payers. In contrast, provisions in the health reform law to address Medicare readmissions apply only to hospitals with excessive rates of readmissions related to specific conditions—heart attack, congestive heart failure and pneumonia—and do not provide incentives to other hospitals to lower readmission rates or lower costs.

Challenges to Rate Setting

To some policy makers, rate setting represents an unacceptable intrusion into the marketplace, but the status quo may be even more unpalatable. If prices paid by private insurers continue to grow at high rates, private health insurance premiums will increase accordingly, making health insurance less affordable for more Americans.

State experiences with hospital rate setting demonstrate that rate regulation can hold down spending on hospital services, but serious challenges would confront any state contemplating adoption of a hospital rate-setting system. The most significant challenges include building a broad reservoir of good faith and insulating regulators from day-to-day political pressures. Hospitals can apply intense pressure on a rate-setting body if its decisions are not perceived as fair and based on evidence. And, given the importance of the health sector as a source of local jobs and economic expansion, resistance to rate regulation should be expected.28

Over the long run, decisions about governance and leadership may be more critical to the success of rate setting than the technical details of payment formulas. Enabling legislation that sticks to broad objectives yet allows regulators room to maneuver and respond to changes in market behavior will give a rate-setting system greater resilience over the long run.

Notes

1. Strunk, Bradley C., Kelly J. Devers and Robert E. Hurley, Health Plan-Provider Showdowns on the Rise, Issue Brief No. 40, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (June 2001).

2. American Hospital Association (AHA), TrendWatch Chartbook 2011: Trends Affecting Hospitals and Health Systems, Washington, D.C. (2011).

3. White, Chapin, Health Status and Hospital Prices Key to Regional Variation in Private Health Care Spending, Research Brief No. 7, National Institute for Health Care Reform, Washington, D.C. (February 2012); Ginsburg, Paul B., Wide Variation in Hospital and Physician Payment Rates Evidence of Provider Market Power, Research Brief No. 16, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (November 2010); Reschovsky, James D., et al., “Durable Medical Equipment and Home Health Among the Largest Contributors to Area Variations in Use of Medicare Services,” Health Affairs, Vol. 31, No. 5 (May 2012); and Berenson, Robert A., Paul B. Ginsburg and Nicole Kemper, “Unchecked Provider Clout in California Foreshadows Challenges to Health Reform,” Health Affairs, Vol. 29, No. 4 (April 2010).

4. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Report to Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, Washington, D.C. (June 2011); Office of Attorney General Martha Coakley, Examination of Health Care Cost Trends and Cost Drivers, Report for Annual Public Hearing, Boston, Mass. (June 22, 2011); Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner, State of Rhode Island, Variations in Hospital Payment Rates by Commercial Insurers in Rhode Island (January 2010); and Robinson, James, “Hospitals Respond to Medicare Payment Shortfalls by Both Shifting Costs and Cutting Them, Based on Market Concentration,” Health Affairs, Vol. 30, No. 7 (July 2011).

5. Eight states regulated hospital rates through a minimum of mandatory review and compliance with a rate-setting authority: Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Washington, Wisconsin and West Virginia. Illinois never implemented its program. A much larger number relied on voluntary or mandatory participation in some form of budgetary review by a nongovernmental association and voluntary compliance.

6. Studies found savings in per-capita spending, but effects were weaker and less robust than per-unit cost reductions. See Morrisey, Michael, A., Frank A. Sloan and Samuel A. Mitchell, “State Rate Setting: An Analysis of Some Unresolved Issues,” Health Affairs, Vol. 2, No. 2 (May 1983).

7. Biles, Brian, Carl J. Schramm and J. Graham Atkinson, “Hospital Cost Inflation Under State Rate-Setting Programs,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 303, No. 12 (September 1980); Schramm, Carl J., Steven C. Renn and Brian Biles, “Controlling Hospital Cost Inflation: New Perspectives,” Health Affairs, Vol. 5, No. 3 (August 1986); Broyles, Robert W., “Efficiency, Costs, and Quality: the New Jersey Experience Revisited,” Inquiry, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Spring 1990); Rosko, Michael D., “A Comparison of Hospital Performance Under the Partial-Payer Medicare PPS and State All-Payer Rate-Setting Systems,” Inquiry, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Spring 1989); Zuckerman, Stephen, “Rate Setting and Hospital Cost Containment: All-Payer Versus Partial-Payer Approaches,” Health Services Research, Vol. 22, No. 3 (August 1987); and Hadley, Jack, and Katherine Swartz, “The Impacts on Hospital Costs Between 1980 and 1984 of Hospital Rate Regulation, Competition, and Changes in Health Insurance Coverage,” Inquiry, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1989).

8. Atkinson, Graham, State Hospital Rate-Setting Revisited, Issue Brief, Pub. No.

9. Rosko, Michael D., “Impact of the New Jersey All-Payer Rate-Setting System: An Analysis of Financial Ratios,” Hospital & Health Services Administration, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Spring 1989); and Rosko, Michael D., “All-Payer Rate-Setting and the Provision of Hospital Care to the Uninsured: The New Jersey Experience,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, Vol. 15, No. 4 (1990).

10. West Virginia Code, Chapter 16, Article 29B, Section 1, as enacted in 1983. The law froze hospital revenues for one year, and a rate review process was implemented in 1984, so 1985 became the first year projected revenues were subject to the budget review process.

11. McDonough, John E., “Tracking the Demise of State Hospital Rate Setting,” Health Affairs, Vol. 16, No. 1 (January 1997).

12. Murray, Robert, “Setting Hospital Rates to Control Costs and Boost Quality: The Maryland Experience,” Health Affairs, Vol. 28, No. 5 (September/October 2009).

13. Atkinson (2009).

14. Murray (2009).

15. Personal communication with Robert Murray, who served at the time as executive director of the Maryland Health Services and Cost Review Commission (May 6, 2011).

16. In 1991, amendments required the HCA under West Virginia Code, Chapter 16, Article 29B, Section 19A to develop a cost-based rate review system and methodology. Amendments in 1999 under Chapter 16, Article 29B, Sections 19, 19a and 20 established an alternate benchmarking methodology that effectively applied to rate updates requested for 2000.

17. Between 1993 and 2007, costs per unit increased 51.3 percent in West Virginia and 60.4 percent in the nation. Costs per unit were calculated as hospital costs per equivalent inpatient admission. Calculations by authors based on state-year estimates from Atkinson (2009).

18. Zuckerman, Stephen, and John Holahan, “PPS Waivers: Implications for Medicare, Medicaid, and Commercial Insurers,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, Vol. 13, No. 4 (1988).

19. Section 1886(c)(1)(C) of the Social Security Act requires such waivers in Medicare to assure federal budget neutrality.

20. Personal communication with Murray (2011).

21. West Virginia Code, Chapter 16, Article 29B, Sections 5 and 6.

22. Ginsburg (November 2010).

23. Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner, State of Rhode Island (January 2010).

24. In West Virginia, hospitals may choose to accept the guaranteed rate increase (minus any penalties) set by the Benchmarking Application Methodology, or they may apply for a higher rate increase under standard application, which is subject to a lengthy review and for which a cost-based methodology is used to assess the merits. In 2011, a large majority of hospitals accepted rate increases based on the benchmarking methodology because it is expeditious, personal communications with Barbara Skeen, director, and Marianne Kapinos, general counsel, West Virginia Health Care Authority (June 21, 2011, and Nov. 16, 2011).

25. Personal communication with Murray (2011).

26. Office of Attorney General Martha Coakley, Examination of Health Care Cost Trends and Cost Drivers, Report for Annual Public Hearing, Boston, Mass. (March 16, 2010).

27. Health Services and Cost Review Commission, Template for Review and Negotiation of an Admission-Readmission Revenue (ARR) Hospital Payment Constraint Program, Baltimore, Md. (Jan. 12, 2011).

28. White, Chapin, and Paul B. Ginsburg, Working at Cross Purposes: Health Care Expansions May Jumpstart Local Economies but Fuel Nation’s Fiscal Woes, Commentary No. 5, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (August 2011).

Data Source

In addition to performing a literature review focusing on hospital rate setting, HSC researchers conducted interviews with staff from the Maryland Health Services Cost and Review Commission and the West Virginia Health Care Authority.

About the Authors

Anna S. Sommers, Ph.D., is a senior health researcher at the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC); Chapin White, Ph.D., is a senior health researcher at HSC; and Paul B. Ginsburg, Ph.D., is president of HSC and research director of the National Institute for Health Care Reform.