While many proposed delivery system reforms encourage primary care physicians to improve care coordination, little attention has been paid to care coordination for patients treated in hospital emergency departments (EDs). As more people become insured under health reform coverage expansions, ED use likely will increase, along with the importance of better coordination between emergency and primary care physicians. This qualitative study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) examined emergency and primary care physicians’ ability—and willingness—to communicate and coordinate care, finding that haphazard communication and poor coordination often exist. This discontinuity undermines effective care through duplicative treatment and misapplied treatment. In addition, primary care physicians lose opportunities to educate their patients about when it is appropriate to use emergency departments and to learn about gaps in their own availability that may be driving unnecessary utilization by patients. Correcting these discontinuities may require a much broader commitment to interoperable information technology, investments in care coordination and malpractice liability reform than currently envisioned.

- Emergency Care: The Path of Least Resistance

- Clinical Communication and Care Coordination

- The Clinical Encounter

- Communication Barriers

- Other Barriers

- Policy Implications

- Notes

- Data Source

Emergency Care: The Path of Least Resistance

Americans are frequent users of emergency departments, seeking care for a variety of problems, ranging from those requiring the resources of an ED to complaints that could be treated in a primary care setting, or nonemergent care. Under health reform, an estimated 32 million people will gain health coverage by 2019. Since insured people are much more likely to seek care in emergency departments, ED use will likely increase significantly. In addition, many newly insured people will be covered by Medicaid, whose enrollees have the highest rates of ED utilization of any group, possibly because of less access to primary care.1-3

Moreover, inadequate primary care capacity could lead to higher than usual rates of ED use for the newly insured. Although policy makers are focusing on increasing primary care capacity, even the most ambitious attempts may require at least a decade to increase capacity in a meaningful way. Even among patients who have primary care providers, changing patient—and provider—behavior to limit inappropriate emergency department use has proved a complex and challenging task.4,5 For all of these reasons, emergency care, for both emergent and nonemergent complaints, will continue to be a significant component of overall health care utilization.

Care-delivery reforms, such as the patient-centered medical home, are aimed at strengthening the role of primary care providers in coordinating care. Because avoiding emergency department utilization is a goal of the patient-centered medical home, these tools appear most suited for coordination with ambulatory specialty care, rather than with emergency care providers. Nevertheless, as in all other areas where providers share responsibility for a patient’s care, lack of coordination between primary and emergency care can put patients at risk and potentially make the services delivered in both settings less efficient.

This study focuses on how primary care and emergency physicians currently communicate with each other about coordinating patients’ care. Research has examined transitions in care during emergency department shift changes6 and between emergency physicians and inpatient admitting physicians—usually hospitalists7—as well as coordination between EDs and safety net clinics.8 But, little attention has been given to care coordination between emergency and primary care physicians.

This Research Brief describes current patterns of emergency and primary care physician communication and coordination, reviews the ways that communication and coordination can affect care, and discusses common barriers to communication. HSC researchers interviewed 21 pairs of physicians—an emergency physician and a primary care physician whose patients seek care in that emergency department (see Data Source).

Clinical Communication and Care Coordination

When and how communication happens. Care coordination in the emergency department draws on many sources of information, including the patient, family members, the patient’s usual primary care physician (PCP) or practice partners, and/or the patient’s medical record. Most obvious are patients themselves, along with family members or caretakers. However, physicians agreed that patients, particularly in moments of pain, confusion and distress, often are limited or unreliable historians. “It’s amazing what people don’t tell you,” an emergency physician (EP) said.

Primary care providers also can be involved in the coordination process, either directly or through information they have placed in an electronic medical record (EMR). Primary care physicians often share call responsibilities with other physicians in their practices, so an emergency physician trying to reach PCPs after hours might speak to one of their partners, who may or may not have knowledge of the patient or access to the patient’s medical record. For patients with frequent ED visits and hospitalizations, emergency department and inpatient records may also be valuable information sources.

When they do communicate, emergency and primary care physicians most commonly communicate by telephone. Many emergency physicians also reported using systems where their records are automatically faxed to the offices of primary care providers affiliated with their hospital after the patient’s discharge. Depending on when the ED notes are signed and entered into the patient’s medical record, this may involve a delay. In cases where emergency and primary care physicians share a common EMR, the emergency physician may leave a note directly in the record for the primary care physician, although shared EMRs are the exception rather than the rule.

Rarely, providers reported communicating with each other through e-mail and text messaging. In a few cases, emergency physicians reported using hospital-employed care coordinators to facilitate real-time communication among emergency physicians, primary care physicians and hospitalists. These coordinators generally focus on chronically ill patients with frequent hospital admissions who have been identified as targets for intensive case management.

Communication patterns have changed. The increasing use of hospitalists to authorize inpatient admissions from the ED has reduced the frequency of communication between emergency and primary care physicians. Before the wide advent of hospitalists, primary care physicians would generally admit patients to the hospital and manage their care while they were hospitalized. This required PCPs to speak with emergency providers at the time of admission and visit hospitals in person at least daily to conduct patient rounds. PCPs’ frequent physical presence in the hospital created opportunities for interaction and the development of relationships between emergency and primary care physicians, which in turn made providers more likely to contact each other regarding shared patients. This routine notification may no longer occur if a PCP’s patients are admitted by a hospitalist. Several PCPs reported never being informed of their patients’ admission to a hospital, most frequently when their patients were admitted to hospitals where the PCP lacked admitting privileges. One PCP reported that he sometimes deduced that his patients had been hospitalized when he received routine copies of radiology reports that listed an inpatient room number.

Many primary care providers reported that since they began using hospitalists and stopped going to the hospital on a regular basis, they had less communication with emergency providers, not just regarding patients who were admitted, but also patients who were discharged from the ED and needed follow-up care. “I think it has carried over even [to the care of] discharged patients,” an EP said. “The PCPs don’t get involved; we don’t associate any more or see them in the lounge. We just don’t communicate anymore because we don’t see each other anymore.” Primary care physicians who admit their own patients believed they had stronger relationships and better communication with emergency physicians because of their continuing presence in the hospital.

EPs and PCPs have few clinical standards to guide them in coordinating care for patients who are in the emergency department. “It’s not a system,” one PCP said. “It depends on the goodwill and training of the individual on the other side.” Highlighting the variation in communication, an EP said, “There are some people that will call every primary—that is just their personal style, and some will never call a primary even if you held a loaded gun to their head.”

Existing guidelines tend to be vague and open to interpretation. For example, the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference9 determined that communication for the purpose of care coordination should be timely and should directly include both physicians involved in a patient’s care. The National Quality Forum has proposed guidelines,10 but they also do not provide specific guidance to physicians seeking to understand the standard of care. In part, this reflects the diversity of emergency care, where a broad range of patients—from those with acute, critical illness to those whose needs could be managed more effectively in other settings—seek treatment at all hours. For this reason, communication between primary care and emergency physicians is often qualitatively different from communications between primary care physicians and other specialists. As stated in the Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement, “This variety of variables precludes a single approach to ED care coordination.”11

The Clinical Encounter

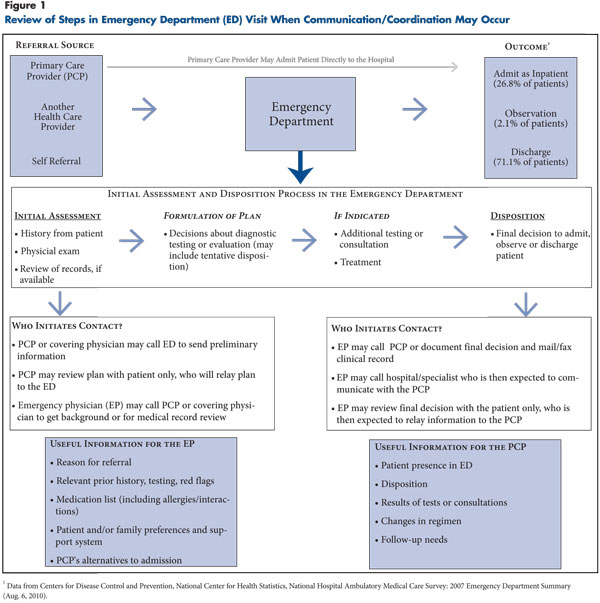

Physicians described several points in the ED encounter when communication could occur, from the patient’s entry to the ED through final disposition (see Figure 1). But interaction at some points could be more challenging—or more useful.

Initial assessment. When referring patients to the emergency department, many PCPs said they send patient information by fax or speak directly with an ED physician about the patient’s history and the reason for the ED visit. Emergency physicians reported, however, that they frequently did not receive information on patients referred from a primary care office, suggesting that a significant number of PCPs do not send information with their referrals or that information is lost in transit once it reaches the ED and never reaches the patient’s chart. “The vast majority [of patients] just show up and say ‘My doctor told me to come over here,’” an EP said.

Both emergency and primary care physicians agreed that referring PCPs who notify the ED of the reason for the referral can help to streamline care and ensure concerns are addressed. PCPs’ information, when available, “helps guide you and avoid duplicates with resource utilization. It probably gets you to managing the patient a little quicker,” an EP said.

Formulation of plan. After a patient has been evaluated in the ED, but before a definitive plan of care has been determined, emergency physicians reported they would only rarely contact primary care providers to clarify key points in the patient’s history or gather additional information. In cases where a shared EMR was available, emergency physicians reported reviewing records of previous visits or hospitalizations. However, they were less likely to contact PCPs. One PCP expressed frustration, saying, “I always offer feedback, but often it is past the point where my feedback is worth anything when it comes to admissions or testing, because often they have already done it.”

Many primary care and emergency physicians agreed that communication and coordination can help emergency physicians as they formulate plans of care, particularly for patients with chronic illnesses who may have complex medical histories. “I was going away for the weekend and signed out my pager, but got an e-mail saying one of my frail elderly patients had just registered in the ED,” one PCP said. “So I called and spoke to the triage doctor. And the doctor said, ‘OK, I haven’t seen her yet.’ I said, ‘Well, hold on. I know this person really well. She has all these problems, but the complaint she is coming in for is the same thing she has had for the past year, and here is what you might do.’ And he said, ‘Great, that is very helpful. If I can confirm what you told me, I will do what you said, and if not I will call you back.’ And I got an e-mail in 15 minutes saying [the patient] would be discharged.”

Another PCP relayed a similar story: “We had a patient with some psychological issues. The EP saw [this patient] and…was having a difficult time gaining a good sense of how severe her present condition was compared to her normal condition….So [the EP] called and said ‘This is what the patient is telling me. What is her baseline?’ And we were able to say that what the patient was saying is kind of a norm[al thing for her]. So that saved an admission.”

Disposition. When a patient will be discharged and need prompt re-evaluation, emergency physicians were most likely to contact primary care physicians to ensure follow-up care would take place. Primary care physicians who said emergency physicians regularly contacted them to coordinate follow-up care reported this kind of contact was extremely helpful. Others reported struggling to guess what had happened to their patients in the emergency department when they were discharged without communication.

“Sometimes we try to piece together what happened based on the handouts a patient gets [in the ED]…It’s that primitive,” one PCP said. When timely follow up is not required—for example, when a patient is seen for an uncomplicated illness—emergency physicians were much less likely to contact primary care physicians. In turn, PCPs reported that they did not want or need immediate communication about these patients, although some said they would like notification of the ED visit to be sent to them.

PCPs and EPs agreed that coordination was helpful in ensuring that patients could be safely admitted or discharged with a follow-up plan. Without communication, a PCP said, “Sometimes you get patients back, and they were put on a medication they didn’t tolerate a year ago, and they are back at square one.” Some PCPs believed that if they were contacted before emergency physicians performed diagnostic testing or made the final determination of whether to admit or discharge their patients, they could advocate for less-costly, less-intensive plans of care.

“From our point of view, a lot of admissions, we think, can be avoided if we know the patient,” a PCP said. “I can usually reassure [EPs] that the patient will have follow up, so they feel comfortable releasing them,” another PCP said. “A lot of times, [PCPs calling to discuss a planned admission] will say, ‘You know, I can see them tomorrow.’” An EP said, “There are definitely times where I would probably err on [the side of] discharging people if I were going to talk to the primary.”

Primary care physicians reported that lack of timely information about their patients’ ED visit could make follow-up care inefficient or incomplete. “I didn’t get the records [for a follow-up visit] until after 5 that night,” one PCP said. “We called all day, and I ended up having to call the patient back later that night because their records [when they arrived] told me more information that I had not known.”

In cases where patients sought emergency care for nonemergent complaints, primary care and emergency physicians agreed that direct communication would rarely affect the patient’s treatment. Most PCPs believed communication offered no benefit at all for these patients, and emergency physicians agreed that direct communication about all patients with nonemergent conditions would be highly impractical. “I certainly would not want to be contacted about all ED visits,” a PCP said. “We would love faxes on all, but not a phone call. I don’t think that would be worth anyone’s time.”

However, many emergency physicians believed strongly that primary care physicians should be informed quickly—for example, through automatic notifications in an EMR—of their patients’ nonemergent ED utilization. “I think the PCPs have little idea how often their patients are going to the ER, because they don’t have access to the record,” one EP said.

Many emergency physicians believed that patients struggle to reach their primary care provider after regular business hours, and that even during business hours, the staff of primary care offices sometimes “gatekeep” by encouraging patients who call with concerns to go to the ED for care, rather than trying to fit those patients into already-crowded office schedules.

“A lot of times when a patient could be seen at the PCP’s office, the nurses will [send] patients to the ER,” an emergency physician said. “And a lot of times the PCP doesn’t have a clue that their patient called.” Only by being notified of their patients’ nonemergent ED utilization in a timely manner can primary care physicians know whether they are offering adequate access to their patients, according to emergency physicians (see Table 1 for a summary of how coordination can affect emergency and primary care for different types of patient presentations).

Communication Barriers

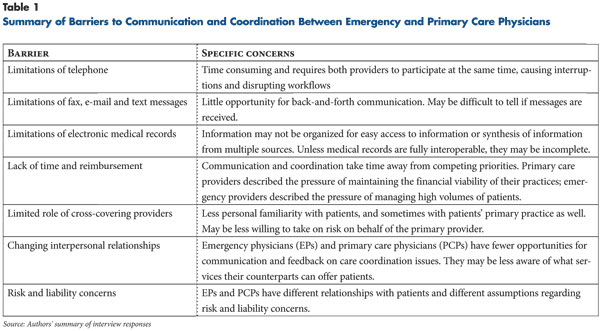

Physicians described several barriers to improved communication and coordination of care. Some of these were specific to particular communication modes, while others were overarching issues affecting all types of communication.

Real-time communication: telephone. While alternative communication methods could be useful in many cases, real-time, physician-to-physician communication was essential in some circumstances, according to respondents. However, they agreed that communicating via telephone was particularly time-consuming. Both emergency and primary care physicians reported that successful completion of each telephone call often required multiple pages and lengthy waits for callbacks. “It’s really fragmented and frustrating on both sides,” one EP said. “It’s frustrating for the PCP and for us trying to get stuff back. We can’t sit around and wait for two hours for them to call us back.” Likewise, another EP said, “When you’re making the second or third phone call to try and reach the attending [PCP], you lose the desire to keep working at it.”

Callbacks, when they do arrive, frequently interrupt patient care, increasing the risk of medical errors and disturbing patients whose care is being interrupted to accept the call.12 “If you are in the middle of a rectal exam, you don’t take [the call],” an EP said. “Same with [the PCPs] if they are in the middle of a patient encounter. It’s hard to find a time [to speak] together when you are not disrupting the workflow.” Finally, the time consumed in care coordination decreased physician productivity and often added to patients’ length of stay in the ED, which can affect emergency physicians’ compensation either directly—if their pay reflects length of stay—or indirectly through decreased bed turnover and volume.

In turn, primary care physicians described calls from emergency departments as disruptive to their office schedules. “It is hard to [speak with] the ER when you have 12 patients breathing down your neck,” a PCP said. Primary care physicians reported that when they did call back, they faced lengthy waits on hold since the emergency physician had generally moved on to a new task and had to be pulled away to take their telephone call.

Several PCPs said that the work of reviewing patient records, discussing them over the telephone, and returning their focus to the task at hand took about as much time as a patient visit but, unlike a patient visit, was not reimbursed. This issue was highlighted by physicians working in small, independent practices because of the effect on the financial viability of the practice. Primary care physicians also reported that interruptions during patient care increased their risk of error. “When I hear an ER doctor is on the line, I hate it,” another PCP said. “I hate any phone call. Say you are doing a math problem, and you are on step 16 of a 30-step problem…you will lose it [if you are interrupted].” As one EP summarized, “You know, the ideal of physician-to-physician communication makes so much sense intuitively, and there is so much emphasis on it, but it’s really a very inefficient model.”

Asynchronous communication: fax, text message and e-mail. Asynchronous modes of communication did not require breaks in task but had significant limitations as well. Faxed records can be reviewed at providers’ convenience but do not provide an opportunity to converse in real time and ask questions. Physicians had little confidence that faxes were carefully reviewed by their intended recipient and often reported that faxed records were poorly organized and difficult to decipher. “What used to be a few pages is now 20-30 pages” of ED record, one PCP said.

Newer modes of communication, such as e-mail and text messages, combine the benefits of telephone and fax but have significant limitations as well. They are timely and allow for back-and-forth communication; providers can integrate reading and responding to messages into their existing workflow—for example, by quickly responding to text messages between interactions. However, few providers reported they had incorporated these types of messaging into their EMRs or encouraged the use of text pagers.

A further question is whether such messages offer any liability protection to the sender. In cases where a provider’s message is not quickly returned, he or she has no way of knowing whether it was, in fact, received. “I could send someone a text message or an e-mail to their Blackberry,” an EP said, “but I need the kind of rapid response you get on the phone. I don’t want to send an e-mail out to never-never land. The concern about dropping a note in a medical record that won’t be seen or acted on is still a little scary to me.” In the event that an e-mail or text message does not trigger a rapid response, the sending provider would likely consider it prudent to act as if the message had been lost, limiting its value as a mechanism for coordinating care.

Shared electronic medical records. Sharing information through a fully interoperable electronic medical record, such as those shared in hospital systems that own primary care and specialty practices, can address some barriers but leave other key problems unresolved. In this model, emergency physicians could read patients’ medical records to learn their history and could alert primary care physicians about their patients’ ED visits by flagging a note for their review or triggering an e-mail directing them to review the record. These approaches could be supplemented with telephone calls as needed, although emergency physicians with access to these systems reported less need to call primary care physicians and virtually no need to call providers who are covering for the primary care physician, since they would likely be reading from the same record.

The benefits of a shared record, of course, only apply to patients who obtain all of their care within a single integrated health system. If EPs and PCPs use separate EMRs, “for me to get into [their] EMR I need to click on the icon, load it up on the Web, put in my password, go to the record, find a place in the record to send the notes,” an EP said. “If things were integrated so I could send the note right when I’m doing the ED documentation, that’s probably something I would do more frequently.”

However, the reality is that many PCPs are on separate EMR platforms, making a common process among these groups extremely difficult to achieve. Having access to a partial—but incomplete—medical record may give providers a false sense of security. A PCP described an ED visit where his patient’s hospital medical record did not include a recent outpatient specialist visit that had diagnosed the cause of her chronic condition. The EPs “were pulling up old data, and the patient was a little confused and was assuming they had access to the current stuff. They did not. They were repeating old, incorrect information.”

Relying on EMRs for coordination and communication creates a new set of problems as well. “Having IT in common doesn’t guarantee we will look at it in the right way,” a PCP said. Electronic medical records are valuable tools for billing and liability documentation but are not designed to offer a rapid overview of a patient’s case that is relevant to a particular problem with the level of detail that could help an emergency provider direct care.13 “You have a transplant patient with thousands of notes, and even the summary can run on for many pages,” a PCP at an academic medical center said. “So the ED doctors are faced with too much information.” While some key information can be obtained by a fairly cursory read through medical records (e.g., problem list, medications), other important aspects, including the level of clinical detail emergency physicians would require to make a high-risk decision, are much more efficiently communicated by someone who has personal knowledge of the patient.

Other Barriers

Providers also cited a number of barriers that were not specific to any one communication modality. These included issues that are deeply embedded in the practice of medicine, such as reimbursement and payment systems and medical liability.

Lack of time and reimbursement. Emergency and primary care physicians most commonly cited insufficient time and lack of reimbursement as significant barriers to communication. While the activities of care coordination—for example, placing and receiving telephone calls—might seem straightforward and quick, providers noted that each small action multiplied across dozens of patients can become a daunting burden, with little immediate reward.

Limited role of cross-covering providers. Another overarching barrier to effective coordination is the role of cross-covering providers. The rise of larger groups and more elaborate cross-coverage systems means that emergency physicians are less likely to speak with a physician who has direct knowledge of the patient. Respondents agreed that time invested in care coordination through a cross-covering primary care physician yielded much less value because they rarely knew the patient and were less likely to offer information or suggestions that would change an emergency physician’s plan of care.

Changing interpersonal relationships. While rising hospitalist use and the growth of larger primary care groups help PCPs decrease their call responsibilities and maintain a more balanced lifestyle, they inevitably decrease interactions between office-based and hospital-based physicians. Many EPs reported that they had no venues for ongoing collaboration with primary care practices in their community, particularly if the community was served by many practices that each offer different resources and have different preferences regarding coordination of care. The rise in hospital ownership of primary care practices may help to facilitate closer ties.

Risk and malpractice liability concerns. Even if practical barriers to communication and coordination are removed, liability concerns may keep providers from participating fully in care coordination. Many respondents noted that emergency and primary care physicians are bound by different constraints and have fundamentally different assumptions regarding patients’ reliability and resilience.

“I am sure [EPs] wouldn’t want to do my job, and I wouldn’t want to do their job either,” said a PCP. “To see 30 new patients each night, and they don’t know how good the [patient’s] history is, what the different people’s agendas are, the family dynamics, all the history that goes with having a chronic illness…I don’t envy it.” Unlike primary care physicians, emergency physicians do not have the opportunity to develop the positive long-term patient-doctor relationships that are considered the most effective protection against being sued for malpractice in the event of a misdiagnosis or a bad outcome. And, emergency physicians have much higher levels of concern about being sued for malpractice than do primary care physicians.14

Policy Implications

What, if anything, can policy changes do to improve the communication and coordination between emergency and primary care physicians? Given many physicians’ concerns that they are not compensated for time spent in communication, it might seem logical to establish a clinically meaningful definition of appropriate communication that can be linked to reimbursement. This approach is unlikely to be effective for several reasons.

First, communication is difficult to measure; the current paucity of guidelines for physicians seeking to coordinate between emergency and primary care reflects the complexity of the problem and the fact that many different levels of communication could be appropriate for different situations. A formal standard for communication would likely be either so detailed as to be burdensome or so broad that it would do little to change care. Second, communication takes time and may conflict with other ED quality or efficiency measures (such as length of stay) that are themselves incentivized, weakening the effect of payments for communication. Finally, care coordination must be fit into the complex workflows of the emergency department and primary care office. Paying for communication may result in the appearance of increased interaction but cannot guarantee that providers will do the work of integrating meaningful coordination into their practice.

However, other approaches may be more effective. In particular, changes in meaningful use criteria for electronic medical records, payment incentives and malpractice liability reform could encourage providers to take advantage of opportunities to coordinate care when available.

Meaningful use criteria. Physicians with access to an electronic medical record shared among emergency, primary care and hospital-based physicians frequently said that such a record would be the best way to foster enhanced communication and coordination of care. However, current meaningful use criteria omit such key elements as easy interoperability or rapid synthesis of information too complex to be found in most clinical summaries.

As providers develop electronic medical records in response to incentives from the federal government, they will be guided by meaningful use criteria, which do not presently support the kind of interoperability that would be required for care coordination with emergency providers. Current meaningful use criteria have no explicit requirements for EPs and PCPs to share information. Future phases of meaningful use criteria will require the development of a “face sheet” that could provide basic information about patients in a standardized format, but this approach has two key weaknesses. First, it is unlikely that a face sheet will contain sufficient detail about any one medical problem to sway physicians contemplating a high-risk decision. Second, a face sheet will only be useful if providers can see it. If emergency and primary care physicians use different EMR platforms, EPs will not be able to access the face sheet, limiting its value. While providers are expected to send information to consultants for more than 50 percent of encounters, this measure may not be sufficient to help PCP-EP coordination as most PCPs could easily achieve it by sending face sheets to specialists with whom patients have scheduled appointments.

Community-wide interoperability would be the most effective way to support PCP-ED communication. Other elements also could be added to meaningful use criteria to facilitate real-time sharing of information, making it more helpful for emergency care. Meaningful use criteria could encourage platform developers to create a privacy-compliant, electronic emergency portal, perhaps linked to the patient portals included in many existing EMRs. For example, emergency physicians could go to a Web-based portal, enter their national provider identifier and an identifier and password provided by the patient, and be granted limited, supervised access to the patient’s outpatient medical record. Rewarding the development of natural language-based or similar intuitive search strategies could help providers navigate a complex medical record or an unfamiliar EMR platform once they have access to it.

Payment reform. Payment reforms that reward both primary and emergency providers for managing utilization can indirectly reward meaningful communication. Changes in the way physicians are employed and paid may have profound effects on the role of communication and coordination of care. In a fragmented system where PCPs work in small, independent practices and emergency departments are staffed by separate, contracted groups of physicians who may cover several hospitals in different communities, encouraging coordination would be an impossible task.

However, as small practices are incorporated into larger groups and hospitals again begin acquiring physician practices, more PCPs will have access to common resources and shared systems. This should facilitate the process of developing protocols for care coordination. Small practices that remain independent may still form networks to take advantage of common resources. Increasing consolidation among PCPs can facilitate communication as EPs have more interaction with the remaining consolidated groups. As each primary care group accounts for a greater proportion of their hospital’s provider staff, hospital-employed or contracted emergency physician groups will have more incentive to work with them.

Broader units of payment—either through policy changes among government payers or new programs developed by private payers—that reward primary care groups and hospitals for controlling costs and utilization may encourage coordination of care. For example, hospitals seeking to limit inpatient readmissions may work not only to ensure timely follow up with primary care providers after hospital discharge, but also to facilitate communication between the ED and primary care practices for patients who return to the ED after hospital discharge—for example, through the use of hospital-employed, midlevel providers who can coordinate alternatives to readmission.

If the costs of emergency care are included with costs of outpatient and hospital care in bundled or episode-based payments, providers will have greater incentives to communicate with each other than they would if emergency care is considered a separate bundle or episode. Even the process of negotiating whether to accept bundled payments as a group would likely lead to much more interaction between emergency and primary care physicians than currently exists.

Policies designed to promote the development of medical homes also may shape communication between PCPs and EPs. Currently, care coordination requirements for medical homes stipulate that medical home providers should communicate with specialist consultants but do not require that they communicate with EPs for after-hours visits, which comprise almost two-thirds of adult ED visits and nearly three-quarters of pediatric ED visits.15 Instead, PCPs are expected to contact patients after emergency department visits, although it is unclear—in the absence of communication with the ED—how they would know that these visits occurred. Strengthening guidelines to emphasize the importance of coordination for unscheduled ED visits, as well as planned specialist appointments, could encourage providers to develop greater after-hours availability and promote sharing of information among cross-covering providers.

In turn, policies that promote PCP-EP communication could strengthen the medical home. An important goal of the medical home is to improve patients’ access to primary care, so that they can avoid emergency department visits altogether. Primary care providers were most concerned about being notified if their patients were experiencing an illness that might require admission or follow up, and many said that they did not need to be notified if their patient visited the emergency department for an acute complaint that could have been addressed in a primary care setting. However, timely notification of acute visits may help medical home providers to understand when their patients most need expanded hours and improved access. Previous studies16 have suggested a discrepancy between PCPs’ assessment of their after-hours availability and patients’ understanding of their access, particularly among patients with “avoidable” emergency department visits.

Rapid feedback on ED visit rates can identify patient misunderstandings, primary care staff gatekeeping and similar issues that could be limiting patients’ ability to access timely primary care. Meaningful use criteria encouraging greater interoperability could play a role here as well, as these record systems could include automated notifications for PCPs when their patients register in the ED.

Malpractice liability reform. Failing to address emergency providers’ concerns about controlling their malpractice liability risk will limit any attempt at encouraging emergency physicians to coordinate with primary care physicians. Current incentives essentially ensure that in most cases the primary care physician, who is most familiar with the patient and can bring the most resources to bear in offering alternatives to hospital admission, is the least likely to be involved in high-risk, resource-intensive decisions made in the ED, such as whether to admit a patient to the hospital or use advanced diagnostic testing. Rather, these decisions are most likely to involve providers—emergency physicians, cross-covering physicians and hospitalists—who have no prior knowledge of the patient and every incentive to be cautious and avoid risk.

Even if an emergency physician reaches a provider who can confidently propose an alternative to testing or admission, however, emergency physicians must accept that the legal responsibility for a bad outcome following a patient’s discharge will likely remain theirs alone. Emergency physicians were particularly concerned that PCPs and hospitalists who push EPs to avoid admitting a patient or to limit other utilization, such as diagnostic testing, are not at equal risk from the decision. Failing to address emergency physicians’ concerns about liability risk—for example by encouraging states to establish coordination of care as a best practice that can offer some form of safe harbor from malpractice claims—will severely limit any attempt to encourage emergency physicians to coordinate with primary care physicians and pursue alternatives to admission.

Notes

1. Weber, Ellen J., et al., “Are the Uninsured Responsible for the Increase in Emergency Department Visits in the United States?” Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 52, No. 2 (August 2008).

2. Newton, Manya F., et al. “Uninsured Adults Presenting to U.S. Emergency Departments: Assumptions vs. Data,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 300, No. 16 (October 2008).

3. Niska, Richard, Farida Bhuiya and Jianmin Xu, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 Emergency Department Summary, National Health Statistics Reports, No. 26, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md. (Aug. 6, 2010).

4. McCusker, Jane, and Josée Verdon, “Do Geriatric Interventions Reduce Emergency Department Visits? A Systematic Review,” Journal of Gerontology, Vol. 61, No. 1 (2006).

5. Riegel, Barbara, et al., “Effect of a Standardized Nurse Case-Management Telephone Intervention on Resource Use in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 162, No. 6 (March 2002).

6. Beharra, Ravi, et al., A Conceptual Framework for Studying the Safety of Transitions in Emergency Care, Advances in Patient Safety, Vol. 2, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Md. (February 2005).

7. Horwitz, Leora I., et al., “Dropping the Baton: A Qualitative Analysis of Failures During the Transition from Emergency Department to Inpatient Care,” Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 53, No. 6 (June 2009).

8. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Urgent Matters initiative, “Best Practices: Improving Care Transitions and Coordination for Frequent ED Users,” Newsletter, Vol. 7, No. 5 (November/December 2010).

9. Convened jointly by the American College of Physicians, the Society of General Internal Medicine, the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Geriatrics Society, the American College of Emergency Physicians and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine.

10. Relevant National Quality Forum standards:

Preferred Practice 22: Health care organizations should develop and implement a standardized communication template for the transitions of care process, including a minimal set of core data elements that are accessible to the patient and his or her designees during care.

Preferred Practice 23: Health care providers and health care organizations should implement protocols and policies for a standardized approach to all transitions of care. Policies and procedures related to transitions and the critical aspects should be included in the standardized approach.

Preferred Practice 24: Health care providers and healthcare organizations should have systems in place to clarify, identify, and enhance mutual accountability (complete/confirmed communication loop) of each party involved in a transition of care.

Preferred Practice 25: Health care organizations should evaluate the effectiveness of transition protocols and policies, as well as evaluate transition outcomes.

11. Snow, Vincenza, et al., “Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement American College of Physicians—Society of General Internal Medicine—Society of Hospital Medicine—American Geriatrics Society—American College of Emergency Physicians—Society of Academic Emergency Medicine,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 24, No. 8 (August 2009).

12. Jeanmonod, Rebecca, et al., “The Nature of Emergency Department Interruptions and Their Impact on Patient Satisfaction,” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 27, No. 5 (May 2010).

13. Hartzband, Pamela, and Jerome Groopman, “Off the Record: Avoiding the Pitfalls of Going Electronic,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 358, No. 16 (April 17, 2008).

14. Carrier, Emily, et al., “Physicians’ Fears of Malpractice Lawsuits are Not Assuaged by Tort Reforms,” Health Affairs, Vol. 29, No. 9 (September 2010).

15. Pitts, Stephen R., et al., National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 Emergency Department Summary, National Health Statistics Reports, No. 7, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md. (Aug. 6, 2008).

16. California HealthCare Foundation, “Overuse of Emergency Departments among Insured Californians,” Issue Brief (October 2006).

Data Source

In addition to performing literature reviews, HSC researchers conducted a total of 42 telephone interviews between April and October 2010 with 21 pairs of emergency department and primary care physicians across 12 communities that are part of the Community Tacking Study. The communities are Boston; Cleveland; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis; Lansing, Mich.; Little Rock, Ark.; Miami; northern New Jersey; Orange County, Calif.; Phoenix; Seattle; and Syracuse, N.Y. Emergency department and primary care physicians were case-matched to hospitals so the perspective of both specialties working with the same hospital could be represented. The respondent sample was selected based on emergency department and primary care practice size to reflect a range of health care settings in the community, including academic hospitals, community hospitals, and a range of employed and independent practices.

After queries about practice and panel characteristics, respondents were asked about each of the following topics: 1) when and how communication and coordination occurs between emergency and primary care providers; 2) whether and how communication and coordination affect patient care; 3) what are the barriers and facilitators to communication and coordination; and 4) how delivery system changes expected under health reform may affect the way emergency and primary care providers communicate with each other.

Respondents were identified primarily through referral by the American College of Emergency Physicians, local primary care associations and respondent referrals. A two-person research team conducted the interviews using a semi-structured interview protocol. Notes were transcribed and jointly reviewed for quality and validation purposes. The interview responses were coded and analyzed using Atlas.ti, a qualitative software tool.