Health insurance benefit structures, particularly cost-sharing amounts, can either encourage or discourage patients from seeking care. The goal is to strike the right balance so out-of-pocket costs don’t discourage people from getting needed care but do prompt them to consider costs before seeking discretionary care. In 2011, contracts between the International Union, UAW, and Fiat Chrysler, Ford and General Motors significantly changed the structure of autoworker health benefits. Generally, coverage of outpatient physician visits was expanded while additional cost sharing was imposed for emergency department visits unless the patient is admitted to the hospital. A new National Institute for Health Care Reform analysis explores the impact of the autoworker health benefit changes on spending and utilization, providing insights into how benefit structures affect access and costs. Generally, lower patient cost sharing for physician visits resulted in substantially higher overall spending, both as a result of more physician visits as well as increased diagnostic services and procedures. However, higher cost sharing did not significantly decrease emergency department visits or expenditures.

Insurance Alters Market Dynamics

The market for medical care differs from other markets in large part because third-party payment leads to insured consumers being less sensitive to costs than if they had to pay out of pocket for care. As a result, health insurance benefit structures usually include patient cost sharing in the form of deductibles, coinsurance and copayments that require consumers to pay some costs of care out of pocket until reaching an out-of-pocket maximum. About half of Americans get health insurance coverage through an employer,1 and over the last 15 years, employers have responded to rising health care spending and insurance premiums by shifting more costs to workers through higher premiums, reduced benefits and greater patient cost sharing.2

Some degree of cost sharing can limit demand for services to help hold overall spending in check, but substantial cost sharing can reduce access to needed care, particularly for people with low or modest incomes. And cost sharing not only can discourage use of services that may be of little value in terms of health outcomes but also care that is important to maintaining health and preventing chronic conditions from worsening.3 As such, cost sharing is a relatively blunt tool to encourage patients to make well-informed care decisions.4

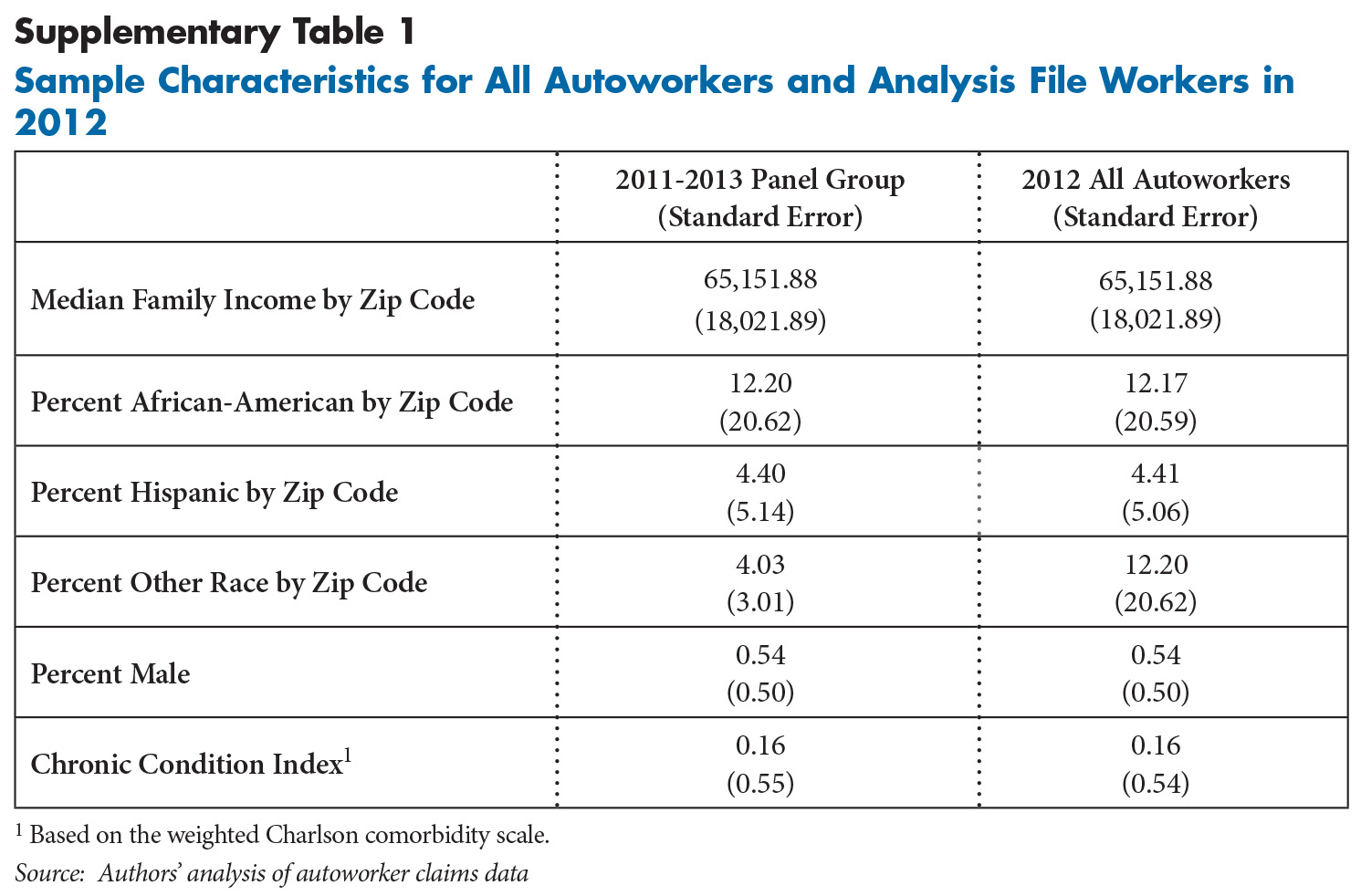

This analysis examines the impact of a change in patient cost sharing on health care utilization and expenditures among active hourly nonelderly autoworkers and their dependents. Since 2007, there have been two categories of autoworkers based on date of hire, with legacy workers receiving more generous health benefits than new workers hired after 2007. Before the 2011 contract changes related to health benefits took effect in 2012, legacy workers faced no cost sharing for most medical services other than outpatient physician visits, while new workers had $300/$600 deductibles for individuals and families, respectively, 10-percent coinsurance for in-network services, and no coverage for outpatient physician visits. New workers also received a contribution to a flexible spending account equal to individual or family deductibles. Although some differences exist across the three companies’ health benefits, the most significant changes pertaining to in-network providers are summarized as follows (see Table 1 for additional details of the benefit changes):

- All outpatient physician visits are covered with a $25 copayment—$20 for Ford—for all hourly workers. Previously, legacy workers were limited to five covered physician visits annually with a comparable copayment, while new workers had no coverage for outpatient physician visits but were able to take advantage of lower negotiated fees if they used in-network physicians.

- For legacy workers, a new $100 copayment was imposed for emergency department (ED) visits not resulting in a hospital admission. Previously, all ED visits were fully covered. New workers saw no change in ED coverage but continued to face deductible and coinsurance costs up to their out-of-pocket maximum.

- A new $50 copayment was added to urgent care visits for legacy workers. Previously, urgent care visits were not a covered service for GM and Ford legacy workers.

The benefit changes that took effect in January 2012 were expected to increase outpatient physician visits and reduce ED visits and spending. Along with improving access generally to physician visits, the expectation was that as cost sharing was reduced for physician visits and increased for ED use in conjunction with more generous coverage of urgent care visits, autoworkers would reduce ED use, especially for care that could be provided in less costly settings.

Moreover, the impact of changes in coverage for physician visits for new workers was expected to be larger than for legacy workers after adjusting for health status differences because new workers had no coverage for outpatient physician visits before 2012, while legacy workers had five visits covered annually. Additionally, new workers on average have lower earnings, which might make them more sensitive to out-of-pocket costs for physician visits than higher-wage legacy workers. Conversely, the $100 copayment for ED visits was expected to affect legacy workers’ utilization more compared to new workers who continued to face deductibles and 10-percent coinsurance.

Autoworker Spending Outpaces Regional Spending

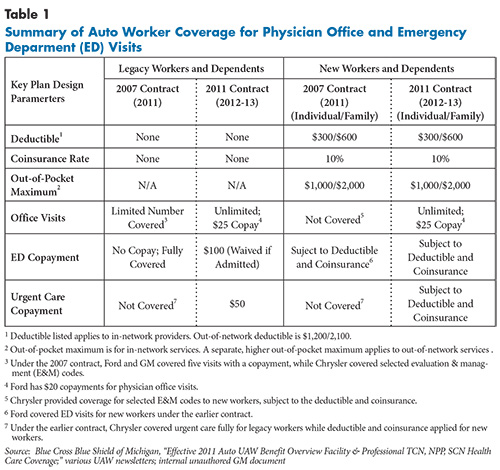

The analysis first compared average per person health care spending for hourly autoworkers and dependents—spending by both the autoworkers and their employers—with published Midwestern U.S. averages from the Health Care Cost Institute, which collects data from several large national insurers (see Data Source and Figure 1).5 Autoworker averages are calculated across full-time workers with 12 months of coverage and enrollment in a preferred provider organization plan. In 2011, average spending per autoworker enrollee was $4,318, slightly lower than the regional average of $4,514. However, in 2012, the first year of the new benefit structure, average autoworker spending rose sharply—nearly 16 percent to $4,990, while regional per capita spending grew 3.6 percent.

From 2012 to 2013, autoworker spending continued to rise but at a slower pace (5.7%) but still higher than the regional growth rate of 4.2 percent. There was a significant difference in average health care spending for legacy and new workers. For instance, in 2012, average health expenditures per new worker and dependents were about 70 percent of legacy workers’, $3,301 vs. $4,766, respectively, likely reflecting that new workers tend to be younger, have lower incomes and face greater cost sharing.

New Workers’ Spending Increases More

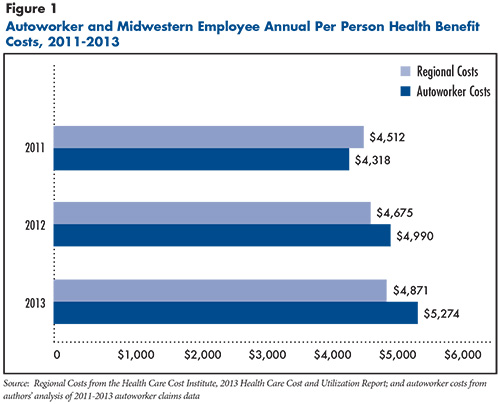

After adjusting for patient characteristics and plan sponsor,6 the benefit structure changes resulted in greater spending on autoworkers and their covered dependents, averaging $207 (4%) more per enrollee annually for legacy workers and dependents and $571 (14%) annually for new workers, despite the latter group being younger and having lower health care spending than legacy workers (see Table 2). At the same time, the likelihood that a covered person had an ambulatory physician visit increased significantly, about 7 percent for legacy workers and more than 18 percent for new workers. Similarly, total spending for physician visits increased by 10 percent for legacy workers and 17 percent for new workers.

Spending Increases for Rx Drugs and Procedures

Physicians often order tests and prescribe drugs as well as perform procedures on patients during visits, so it is not surprising that in addition to higher spending on physician visits, there were significant expenditure increases on prescription drugs and ancillary services. Spending on advanced imaging—such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized tomography (CT)—was nearly $30 and $66 higher per enrollee annually after 2011 for legacy and new workers, respectively, than under the earlier benefit structure.

Similarly, other diagnostic tests were $34 and $50 higher per person annually, respectively, for the two groups. Spending for minor procedures increased an average $56 per capita annually, but the increase was only statistically significant for legacy workers and dependents. Finally, spending on prescription drugs increased $40 and $97 per enrollee annually for legacy and new workers, respectively. Increases in advanced imaging and minor procedures, in particular, suggest that specialist visits likely drove most of the increase in overall spending.

The new benefit structure, however, did not reduce spending on emergency department visits, with both ED visits and spending increasing, but only by small and mostly statistically insignificant amounts for both legacy and new workers. Urgent care costs were too small to examine as a separate category.

Implications

Expanded coverage of physician visits in autoworker health plans in 2012 represented a significant change in benefit structure.7 Generally, collectively bargained health plans are more generous and have less patient cost sharing than other employer-sponsored plans.8 For example, hourly autoworkers pay about 6 percent of their health care costs out of pocket on average, compared with 15.2 percent for workers nationwide.9 Yet, the limited coverage for physician visits before 2012 was one aspect of autoworker plans that was notably less generous than most employer-sponsored plans.

On the one hand, insurance is designed to protect people from large unforeseen health care costs, such as a hospitalization, rather than routine care. On the other hand, costs for physician visits are sufficiently high that lack of coverage could discourage people from seeking important care, such as managing chronic diseases. Additionally, the possibility exists that the large increase in physician visits reflects that claims for some office visits were never filed under the previous benefit structure when the visits were not a covered service. While the large 2012 spending spike was consistent with pent-up demand for physician visits, if that were the case, one would expect spending to decline in 2013, but it did not.

Delays in seeking care can result in bad health outcomes and more expensive care later. As a result, some health plans are covering primary care physician office visits with no patient cost sharing. Insurers hope that offering free visits to primary care doctors will both benefit patients and lower spending by catching illnesses before they become harder and more expensive to treat.10 For example, prescribing antibiotics promptly to a patient with bacterial pneumonia could avoid a lengthy and costly hospitalization.

In addition, free or low-cost primary care visits also might reduce the use of more expensive urgent care centers and emergency departments. Yet, the 2012 increase in the coverage of physician office visits in autoworker health plans did not distinguish between visits to primary care or specialist physicians. In general, greater reliance on primary care physicians is associated with lower health care spending, while use of specialist visits is often associated with higher spending, largely because of increased ancillary services, such as tests and procedures.11

Redesigning health benefits to distinguish between visits to primary care and specialists can be viewed as a component of value-based insurance design (VBID). VBID generally refers to efforts to structure patient cost sharing and other health plan design elements to encourage the use of high-value clinical services—those with the greatest potential to improve health—and discourage the use of ineffective services.

The other major health benefit change that took effect in 2012 was an increase in cost sharing for emergency department visits, which did not significantly affect ED use or spending. The hope was that enrollees would shift utilization from emergency departments to physician offices as the former became more expensive and the latter more affordable. Previous research has found that cost sharing does affect ED use, so the results are somewhat surprising.12 It is possible that the contingent nature of the cost sharing, only applied if the patient is not admitted to the hospital, may have reduced the impact of the $100 copayment on patient behavior.

Moreover, earlier research analyzing the use of emergency departments by autoworkers and dependents found that most enrollees seeking ED care believed they truly had an urgent health problem. Additionally, many autoworkers using emergency departments either were told to go there by their physicians or were unable to contact their normal medical provider when the need arose. As a result, it may be unreasonable to expect emergency department use to be extremely sensitive to financial incentives because few patients visit EDs out of convenience.13 Finally, because ED visits remain relatively infrequent, it may take some time for autoworkers and their families to recognize and respond to changes in coverage for emergency department visits.

Notes

1. Kaiser Family Foundation, State Health Facts, Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population (2014). Available at http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/

2. Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research Educational Trust, Employer Health Benefits, 2015 Annual Survey (2015). Available at http://files.kff.org/attachment/report-2015-employer-health-benefits-survey.

3. Newhouse, Joseph P., and the Insurance Experiment Group, Free for All? Lessons from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. (1994).

4. U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Benefit Design in Health Care Reform: Background Paper-Patient Cost-Sharing, OTA-BP-H-112, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. (September 1993).

5. Health Care Cost Institute, 2013 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report, Washington, D.C. (2013). Available at http://www.healthcostinstitute.org/files/2013%20HCCUR%2012-17-14.pdf.

6. While health benefits across the three auto companies are similar, there are some differences. Ford, for instance, has a copayment of $20 for outpatient visits, lower than the $25 copayment faced by GM and Fiat Chrysler workers and their dependents.

7. Some of the increase may be an artifact in that doctor visits may not have been recorded in claims in 2011 because no insurance payment was made.

8. Gabel, Jon R., et al., “Bargained Health Plans: More Comprehensive, Less Cost Sharing Than Employer Plans,“ Health Affairs, Vol. 34, No. 3 (March 2015).

9. Gardner, Greg, “UAW-GM Deal Would Improve Newer Workers’ Health Plan,“ The Detroit Free Press (Oct. 29, 2015). Available at http://www.freep.com/story/money/cars/general-motors/2015/10/29/uaw-gm-deal-would-improve-newer-workers-health-plan/74800050/.

10. Galewitz, Phil, “Obamacare Insurers Sweeten Plans with Free Doctor Visits,“ Kaiser Health News (Jan. 4, 2016). Available at http://khn.org/news/obamacare-insurers-sweeten-plans-with-free-doctor-visits/?utm_campaign=KHN%3A+Daily+Health+Policy+Report&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=24959366&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-8VSKOT0huSb-g2zTrdUEZWbUWnEHgd_3z6DXfCZaJRd3aaS02HWO6fOo2VptnEsFVwewk43-_4sqNs2WzHLXmd2SAYXg&_hsmi=24959366.

11. Friedberg, Mark W., Peter S. Hussey and Eric C. Schneider, “Primary Care: A Critical Review of the Evidence on Quality and Costs of Health Care,“ Health Affairs, Vol. 29, No. 5 (May 2010).

12. Selby, Joe V., Bruce H. Fireman and Bix E. Swain, “Effect of a Copayment on Use of the Emergency Department in a Health Maintenance Organization,“ New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 334, No.10 (1996).

13. Carrier, Emily, and Ellyn J. Boukus, Privately Insured People’s Use of Emergency Departments: Perception of Urgency is Reality for Patients, Research Brief No. 31, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (December 2013). Available at http://www.nihcr.org/Urgent-Care-and-EDs.

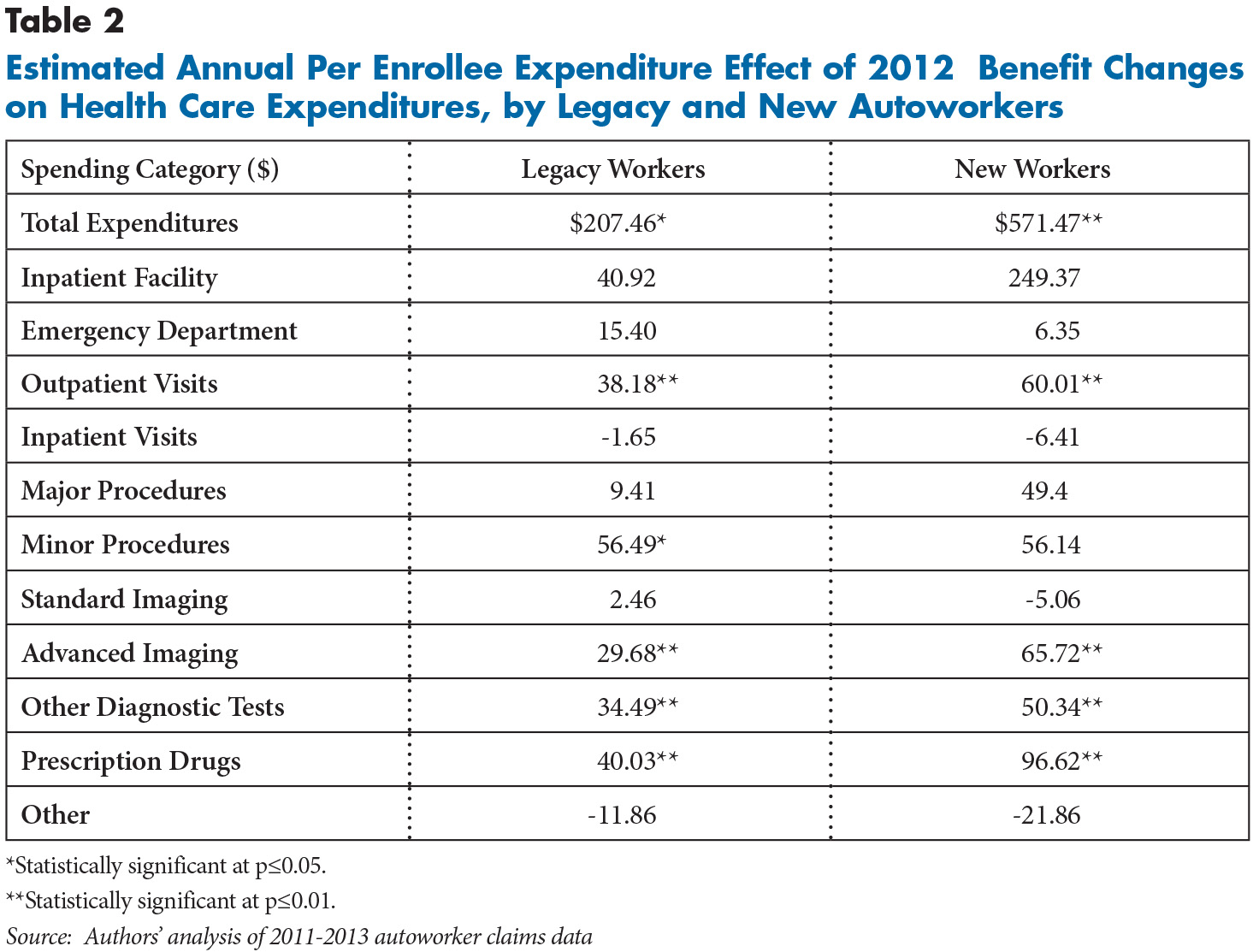

Supplementary Table