Major discrepancies exist between patient preferences and the medical care they receive for many common conditions. Shared decision making (SDM) is a process where a patient and clinician faced with more than one medically acceptable treatment option jointly decide which option is best based on current evidence and the patient’s needs, preferences and values. Many believe shared decision making can help bridge the gap between the care patients want and the care they receive. At the same time, SDM may help constrain heath care spending by avoiding treatments that patients don’t want. However, barriers exist to wider use of shared decision making, including lack of reimbursement for physicians to adopt SDM under the existing fee-for-service payment system that rewards higher service volume; insufficient information on how best to train clinicians to weigh evidence and discuss treatment options for preference-sensitive conditions with patients; and clinician concerns about malpractice liability. Moreover, challenges to engaging some patients in shared decision making range from low health literacy to fears they will be denied needed care. Adding to these challenges is a climate of political hyperbole that stifles discussion about shared decision making, particularly when applied to difficult end-of-life-care decisions.

The 2010 health reform law established a process to encourage shared decision making, including setting standards for patient-decision aids (PDAs) and certification of these tools by an independent entity. However, Congress has not appropriated funding for these tasks. Along with ensuring the scientific rigor and quality of patient-decision aids, liability protections and additional payments for clinicians are other policy options that may foster shared decision making. In the longer term, including SDM as an important feature of delivery system and payment reforms, such as patient-centered medical homes, accountable care organizations and meaningful use of health information technology, also could help advance health system changes to improve care and contain costs.

- Ensuring Patient Involvement in Decisions

- What is Shared Decision Making?

- Improving Care, Constraining Costs

- Challenges to Shared Decision Making

- A Tipping Point for Shared Decision Making?

- Policy Implications

- Empowering Patients

- Notes

- Data Source and About the Authors

Ensuring Patient Involvement in Decisions

Most patients—assisted and guided by their physicians or other clinicians—want the best information available to make treatment decisions.1 A 2009 survey found that 90 percent of California voters believe doctors should inform patients about the scientific evidence supporting different treatments.2 Patients and physicians also believe patients should be aware of major out-of-pocket costs before deciding on a treatment approach.3

However, major discrepancies exist between patients’ preferences and how medical decisions actually are made.4 In a study of more than 1,057 office visits involving 3,552 medical decisions, less than 10 percent of the decisions met even minimal standards for informed decision making.5 Other research indicates that patients are much more likely to receive the care they want if they discuss their preferences with their physicians.6 The same study found that while 60 percent of seriously ill Medicare patients preferred palliative care to more aggressive interventions, only 41 percent believed their care reflected their preferences. In terms of decisions about end-of-life care, the percentage of patients’ advance directives that are followed is low and is often associated with factors other than patient preferences or prognoses.7

Along with clear evidence that many patients do not receive care according to their preferences and wishes, significant variation exists in the volume and mix of services patients receive—sometimes unrelated to evidence of the treatment’s effectiveness or to baseline population health characteristics.8 Reasons for this variation include misaligned payment incentives that can steer providers and patients away from less-lucrative, evidence-based treatments toward more-costly care of unproven benefit. As a result, patients may receive treatment information that limits their choices and leads to more invasive and costly—but not necessarily more effective—treatments that can potentially compromise their health and quality of life. Misaligned payment incentives also contribute to rising health care costs that add little or no value to patients.9 This policy analysis briefly describes shared decision making, explores SDM’s role in improving the quality of care; reviews challenges to more widespread use of shared decision making; and identifies a range of public and private policy options that could foster shared decision making.

What is Shared Decision Making?

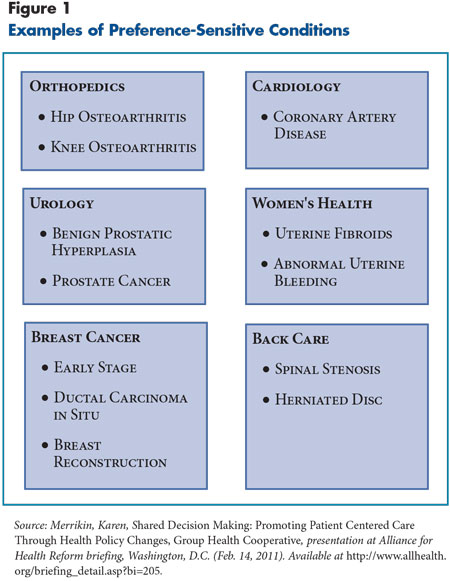

Shared decision making involves patients and clinicians—for example, a physician, an advance practice nurse or a physician assistant—making health care decisions in the context of current evidence and a patient’s needs, preferences and values.10 SDM typically is used for preference-sensitive conditions, or common health problems for which scientific evidence demonstrates more than one medically acceptable treatment option. Some examples of preference-sensitive conditions include low-back pain, early stage breast cancer, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and hip or knee osteoarthritis (see Figure 1 for more examples).

The concept of shared decision making grew from increased recognition of patient autonomy, the consumer rights movement and improvements in medical decision making.11 SDM typically involves a clinician and a patient discussing a treatment decision at the point of care.12 For shared decision making to be informed, the clinician, guided by unbiased and up-to-date evidence, must discuss the risks and benefits of treatment options with the patient, as well as understand the patient’s preferences and personal situation. The goal of shared decision-making is not to “teach the patient everything the clinician knows” but rather to ensure that that there is a two-way exchange of information and preferences in making an informed decision.13

Much of the evidence supporting shared decision making involves the use of patient-decision aids, or PDAs—print, audiovisual and computer-based tools that help to inform patients about preference-sensitive conditions and elicit patient preferences at the point of care. PDAs support communication between patients and health care professionals to help patients understand the range of treatment options available, the likely consequences of different approaches and patients’ preferences. When incorporated into clinical practice for many preference-sensitive conditions, PDAs effectively reduce patients’ conflict about decisions, improve patients’ comprehension and participation, and improve adherence to some treatment regimens and chronic disease control.14

Many groups work to advance shared decision making and the development of patient-decision aids. The International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration (IPDAS) includes researchers, practitioners and stakeholders from 14 countries working to establish international standards to determine the quality of patient-decision aids. Other organizations, such as Healthwise and Health Dialog, contract with health plans to make SDM tools available to providers and patients. Another organization seeking to advance the science and implementation of shared decision making is the Foundation for Informed Decision Making, which works with Health Dialog to develop and make PDAs available to patients.

Improving Care, Constraining Costs

Shared decision making has potential benefits for patients, clinicians and society. People who are fully informed about the risks and benefits of treatments and screening for preference-sensitive conditions, such as low-back pain, use of hormones for menopausal symptoms and prostate specific antigen, or PSA, testing, tend to choose less-invasive—and less-costly—interventions and are happier with their decisions15 (see box below for clinical examples of SDM for two common preference-sensitive conditions.

For example, a program called Respecting Choices in La Crosse, Wis., uses a standardized approach to engage patients and their families in shared decision making about end-of-life care and to improve the way advance directives and care plans are collected, stored and made available in patients’ medical records. An evaluation of Respecting Choices found that 85 percent of adults in the community had advance care plans, and in more than 98 percent of cases, care decisions made at the end of life were consistent with the patients’ wishes as expressed in the advance directive. In addition, average costs of care were well below the national average for patients in the last two years of life.16

Expanded use of advance directives also can help to remove some of the uncertainty that clinicians otherwise would face about steps they should take to ensure a person’s wishes are respected in the delivery of end-of-life care.

Clinical Examples of Shared Decision Making

Management of low-back pain: Mr. Jones, 56, presents with chronic lower-back and leg pain that is limiting his ability to bend, lift, stand and walk for long periods. His wife picked up a brochure at her physician’s office that describes the services of a local spine surgeon, and she has encouraged Mr. Jones to “get it checked out.” Mr. Jones read the brochure, which includes quotes from grateful patients describing how surgery has left them fully functional and pain free, but he is torn because he also has spoken to coworkers who had the same surgery and feel it did not help them or left them worse off. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) scan shows that Mr. Jones has a herniated disc. His primary care physician (PCP) shares data with him suggesting that in his case surgery could be moderately superior to nonsurgical approaches, but that this benefit may fade over a few months. The PCP also shares research suggesting that patients’ own expectations may be a significant predictor of how much they will benefit from surgery, and patients with positive but realistic expectations tend to feel they have improved the most.

Mr. Jones thinks of himself as an active person and wants to pursue whatever course might give him the greatest level of function, even if the advantage is only temporary. However, he still thinks about the extremely positive—perhaps atypical—stories in the surgeon’s brochure, as well as the negative stories his coworkers shared. He believes that these personal stories will inevitably shape his expectations, which may limit his ability to benefit from surgery. He decides to undergo aggressive physical therapy but makes a plan to meet with his PCP after six months of physical therapy for another discussion of his options.

Advance care planning, including palliative care: Ms. Smith, 67, is in good health and recently visited her aunt who is in a nursing home with advanced dementia. Ms. Smith is worried that she may develop dementia herself and schedules an appointment with her PCP to learn if there is anything she can do to prevent it. After reviewing what is currently known about risk factors for dementia, Ms. Smith’s PCP asks her if she would like to discuss her preferences regarding what kind of care she would want to receive if she became incapacitated from dementia or any other reason. They discuss CPR, breathing tubes and feeding tubes.

Because of her religious faith, Ms. Smith believes that she should not refuse any medical care that will prolong her life. For this reason, she determines that she would like to have CPR if her heart stops and intubation if she can no longer breathe on her own. She is uncertain about whether she would want a long-term feeding tube if she is unable to eat. Intuitively, she thinks feeding tubes belong in the same category as CPR and intubation, but she feels uncomfortable about feeding tubes, having frequently watched her aunt become agitated and attempt to pull out her feeding tube and seen nursing home staff members strap oven mitts over her aunt’s hands to protect the tube. Ms. Smith asks her PCP about the risks and benefits of a feeding tube and learns that among patients with advanced dementia, those who receive feeding tubes after they stop eating have not been found to live longer than those who do not have feeding tubes placed. She wonders if, given the evidence that feeding tubes generally do not prolong life in patients with advanced dementia, it would be acceptable for her to decline one under those circumstances in an advance directive. She decides to take an informational DVD and some written material on feeding tubes that her PCP offers so she can discuss them with her pastor.

Sources: Mannion, Anne F., et al. “Great Expectations: Really the Novel Predictor of Outcome After Spinal Surgery?” Spine, Vol. 34, No. 15 (July 1, 2009); Chou, Roger, et al., “Surgery for Low Back Pain: A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society Clinical Practice Guideline,” Spine, Vol. 34, No. 10 (May 2009); and Sampson, Elizabeth. L., Bridget Candy and Louise Jones, “Enteral Tube Feeding for Older People with Advanced Dementia,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, No. 3 (April 15, 2009)

Challenges to Shared Decision Making

While there is considerable interest in shared decision making and patient-decision aids among patient advocacy groups, policy makers, clinician-educators and researchers, the overall use of SDM is limited for a variety of reasons. Physicians are busy and face multiple pressures ranging from fee-for-service payment that encourages delivery of more services at the expense of spending time talking with patients to information overload to marketing by drug and device manufacturers. Additionally, some patients, at least initially, are reluctant to participate fully in the decision-making process for reasons ranging from low health literacy to preferring to “let the doctor decide.” Inter-connected challenges to SDM include:

- The lack of payment for shared decision making contributes to clinician views that there is inadequate time during patient visits for SDM because paid activities take priority.

- The current fee-for-service payment system promotes providers’ use of more-intensive vs. less-intensive interventions to increase revenue and does not reward discussions with patients about the benefits and risks of interventions for preference-sensitive conditions. Likewise, clinician ownership of advanced imaging and other equipment to provide in-office ancillary services creates potential conflicts of interest when existing practices run contrary to evidence of effectiveness.

- Amid insufficient information on the most-effective interventions for increasing health care professionals’ adoption of SDM, many clinicians do not know how to conduct shared decision making.17

- Malpractice liability concerns deter some clinicians because shared decisions that lead to adverse outcomes, even though evidence based, may conflict with local clinical practice.18

- Engaging some patients in shared decision making can be challenging, for example, some patients have low health literacy, low numeracy, multiple chronic conditions or may fear being denied needed care.

- Political hyperbole can stifle discussion and support for shared decision making, as, for example, in the recent removal of advance care planning as a service that could be offered to Medicare beneficiaries during their annual wellness visit.

A Tipping Point for Shared Decision Making?

Widespread calls to improve the quality, value and patient-centeredness of U.S. health care through payment and delivery system reforms may help shared decision making reach a tipping point. The 2010 health reform law19 contains a coordinated approach to fostering shared decision making, complementing initiatives on patient-centered medical homes, accountable care organizations (ACOs) and the “meaningful use” criteria for electronic health records that could incorporate SDM for preference-sensitive conditions as one of their defining features (see box below for more information).

Recent public investments in patient-centered outcomes research—determining which treatments work best for which patients—through the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and the health reform law—emphasize the importance of generating evidence to better inform patient decisions. The purpose of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) established under the health reform law is to generate research to “assist patients, clinicians, purchasers, and policy-makers in making informed health decisions.” Greater use of shared decision making potentially could help ensure that research findings make the leap to clinical practice.

Health Reform and Shared Decision Making

The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable care Act includes provisions to establish a process to certify patient-decision aids, award grants to produce and update aids, create SDM resource centers to assist providers and support effective use of patient-decision aids, provide grants to health care providers to assess SDM tools, and provide support to assess shared-decision-making tools. Further, the law authorizes grant funding for SDM pilot programs. However, no funding was appropriated in the law to carry out the SDM provisions. The secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health and other agencies, is required to establish a program to award grants or contracts to develop, update and produce patient-decision aids for preference-sensitive care to assist in educating patients and others about the relative safety, effectiveness and cost of treatment and test materials to ensure that they are balanced and evidence based. Tools must explain, when appropriate, if there is a lack of evidence to support one treatment option over another and address decisions across the age span and include vulnerable populations.

Patient-Centered Medical Homes: A model of primary care that delivers accessible, patient-centered, continuous, comprehensive and coordinated care to meet, or arrange for, the majority of each patient’s physical and mental health care needs, including prevention and wellness, acute care, and chronic care.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs): An organization of health care providers that agrees to be jointly accountable for the quality, cost and overall care of a population of patients. An ACO may involve a variety of provider configurations, ranging from integrated delivery systems to virtual networks of physicians. The health care reform law requires Medicare ACOs to have a strong base of primary care.

Meaningful Use of Electronic Health Records (EHRs): Under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, HHS has authority to improve health care quality, safety and efficiency through the promotion of health information technology (HIT), including electronic health records and private and secure electronic health information exchange. Eligible health care professionals and hospitals can qualify for Medicare and Medicaid incentive payments when they adopt certified EHR technology and use it to achieve specified objectives.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI): The PCORI’s mission is to generate new evidence to assist patients, as well as clinicians, purchasers and policy makers, in making informed health care decisions.

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMI): The CMI will provide support to test innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce program expenditure while preserving or enhancing the quality of care. Models may be included that “assist individuals in making informed health care choices by paying providers of services and suppliers for using patient decision support tools” [that meet certification standards].

Policy Options

Potential policy options to encourage shared decision making fall into three main areas: reducing barriers to clinician participation, engaging patients and building SDM into systems of care.

Reducing Barriers to Clinician Participation

Lack of reimbursement, lack of training and information on best practices, and fears of malpractice liability all present obstacles to clinician adoption of shared decision making.

Rewarding providers. The existing fee-for-service payment system does not reimburse clinicians for time spent with patients in shared decision making. In the short term, current procedural terminology (CPT) codes for evaluation and management services could be revised to pay for SDM activities. This would require action by the American Medical Association, which owns the CPT coding system, along with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, to devise, for example, a CPT code for an extended evaluation and management office visit for selected preference-sensitive conditions. In another approach, some have suggested requiring providers to use SDM to receive full payment when evidence-based patient-decision aids are available for treatments for certain preference-sensitive conditions.20

There is a risk that paying providers to use SDM could result in a perfunctory check-off box for payment rather than a meaningful exploration of patient preferences. To help avoid this, developing valid measures of whether meaningful shared decision making has occurred would be useful. For example, assessing the “quality of patient decisions,” including whether SDM reduced patients’ decisional conflict and increased their knowledge of risks and benefits of treatment options, would be one way to gauge whether SDM was effective.21

Another approach to rewarding clinicians would be to develop quality measures assessing use of SDM for inclusion in pay-for-performance programs.22 One of the priorities identified by Congress for the new Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation is to develop innovative payment and service-delivery models that assist people in making informed health care choices, which could include testing payment models to use shared decision making and patient-decision aids.

Enhancing clinician skills. If shared decision making is to become a common part of medical practice, clinicians must be trained in its use. Some medical school, residency and fellowship training programs include SDM, and promising curricula for teaching SDM continue to evolve.23 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and medical and surgical specialty boards also could advance SDM by including training and maintenance-of-certification requirements related to SDM and preference-sensitive conditions.

Some have suggested promoting continuing medical education (CME) programs in shared decision making for practicing physicians, which could increase the prevalence of SDM because all practicing physicians must complete CME to maintain state licensure. However, there are few existing opportunities for physicians to gain CME credit for SDM-skills development in the United States. Increasing opportunities for CME related to shared decision making would require professional medical societies, which sponsor CME, to make it a higher priority. Similar approaches could be adopted by the professional societies of other types of clinicians for example, advance practice nurses and physician assistants.

Likewise, making effective educational tools available to providers also could foster adoption of shared decision making. For example, there is an effective curriculum for advance directives—Respecting Choices—that has dramatically increased clinicians’ adherence to patients’ wishes. One way to replicate this effort would be for policy makers to require health care systems to incorporate such approaches into care delivery. For other aspects of shared decision making, fewer clinician training tools exist. However, advances are occurring. For example, a new international interdisciplinary project24 will study how best to translate SDM into primary care through effective continuing professional development, including by teams caring for patients. A main focus of the project is to develop an inventory of SDM training programs, appraise them and identify knowledge gaps to improve implementation of SDM into practice.

Provider quality measures also can foster SDM by creating clear guidelines for providers. Organizations, including the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making, are developing measures of decision quality for preference-sensitive conditions. An independent entity could develop a certification program to help providers gain SDM skills, similar to the National Committee for Quality Assurance designation for physician practices meeting certain standards for diabetes care. To do this, however, it would be important to first ensure that the patient-decision aids used in such a program are certified by a neutral body to avoid conflicts of interest. At present, no organization is truly certifying PDAs. The health reform law establishes a certification process, but no funding has been appropriated by Congress.

Addressing malpractice liability concerns. Physicians under state law must obtain patients’ informed consent before performing various medical procedures, disclosing the risks and benefits of the procedure, as well as any alternatives. The informed-consent process often focuses on satisfying legal requirements to protect physicians and other providers from liability rather than true shared decision making. Evidence suggests that medical decisions in the United States, even momentous decisions, are seldom well informed.25

Current U.S. legal standards in many ways inhibit shared decision making. Some providers are concerned about being sued in case of adverse outcomes where shared decisions, even though evidence based, may conflict with local clinical practice.26 Incorporation of SDM with certified patient-decision aids, where appropriate, into the current legal doctrines of informed consent for preference-sensitive care could help clarify legal requirements for physicians while protecting patients.

Addressing clinicians’ concerns about SDM and liability is feasible. For example, Washington’s Shared Decision Making pilot includes legal protections for physicians who engage in SDM with certified-decision aids as a higher standard for informed consent. Other states are considering similar provisions.

National certification of patient-decision aids by a neutral, independent entity is a prerequisite to including SDM in informed consent, at least if it is to occur in an efficient and nonbiased manner across states. Given that informed consent falls within the legal purview of states, there is a need for state-by-state adoption of shared decision making and patient-decision aids for informed consent related to preference-sensitive conditions. The federal government, by authorizing a framework for shared decision making in the health reform law, has taken the first step toward providing a common, evidence-based standard for SDM and PDA use.

Engaging Patients

Providing access to patient-decision aids, using patient financial incentives and defusing political sensitivities are all possible avenues to engage and encourage patients to be more involved in treatment decisions.

Providing access to patient-decision aids. Engaging patients in shared decision making is facilitated by access to patient-decision aids. Some patients can access PDAs via their health plan. For example, Seattle-based Group Health Cooperative provides members with online access to Web-based tools about 12 preference-sensitive conditions. Some health plans provide PDAs via outside organizations, such as Health Dialog. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Innovations Center also summarizes and provides access to some PDAs. When available, personal health records and patient portals may serve as tools for clinically appropriate PDA distribution. PDA libraries at the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center and the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute also are leading examples of efforts to engage patients in shared decision making. However, patients who are not part of such networks may not have ready access to PDAs. Employers and other benefit sponsors potentially could play a leading role by requiring health plans to provide enrollees with access to evidence-based PDAs.

Some patients can be challenging to engage in SDM, particularly related to complex decisions and self-management of chronic conditions or behavioral modification.27 Providing culturally and linguistically appropriate evidence-based PDAs to patients is critical to encouraging participation in SDM for preference-sensitive conditions. Likewise, policy efforts to address the serious problem of health literacy in the United States the degree to which a person can read, understand and use health care information to make decisions and follow treatment instructions could help empower patients to be more involved in treatment decisions through SDM.

Using patient financial incentives. Financial incentives that encourage patients to use shared decision making are another option. At present, incentives, such as the level of cost sharing for use of particular services is rarely based on effectiveness or potential benefit.28 Some have suggested decreasing or eliminating patient cost sharing for visits where SDM takes place for preference-sensitive conditions. The MedEncentive program offers copayment rebates—$5 to $30—to patients who use Web-based decision aids, as well as incentives for physicians to engage in SDM.29 Another possibility is for payers to require health plans to waive patient cost sharing when patients choose clinicians who use shared decision making.

Defusing political challenges and industry stakeholder resistance. In addition to engaging providers and patients in shared decision making for preference-sensitive conditions, policy makers will need to consider how to address both political and industry challenges to SDM implementation. The recent withdrawal of “advance care planning” as one of the services physicians could offer Medicare beneficiaries during an annual wellness visit illustrates how emotional and volatile public discourse can become about engaging patients in treatment decisions, particularly about end-of-life care.30

Patients do not enter health care encounters or the medical-decision-making process as blank slates. Some patients may bring a historical or personal mistrust of the health care system, making it difficult for them to accept valid evidence that seems to contradict their own or loved ones’ experiences with care. Research shows that many consumers equate more care with better care and that they are skeptical of evidence-based health care.31 These concerns also can be exploited by industries that have a stake in interventions that patients might not pursue if they were fully informed about the risks and benefits of the interventions.

Furthermore, political controversies associated with guidelines for mammography screening, prostate cancer screening and low-back-pain treatment demonstrate that evidence-based guidelines can be used to generate fear and resentment among patients. While evidence is an important factor in shared decision making, a key tenet of SDM is strengthening the patient-clinician relationship, with the clinician in the role of advocate/guide and the patient as informed decision maker.

Emphasizing that SDM is designed to give patients more options, rather than fewer—and that SDM puts the patient, rather than the payer, in the driver’s seat—may help patients understand that taking an active role in decisions is in their best interest. Ultimately, physicians and other clinicians are in the best position to communicate with patients about what care is right for them. To lessen the likelihood of political and industry stakeholder interference in care decisions, policy makers can support the clinician-patient relationship with payment and delivery system reform to encourage and embed SDM into clinical care processes for preference-sensitive conditions.

Building SDM into Systems of Care

Reforming provider payment to move away from fee for service, identifying effective ways to engage providers and patients, and using health information technology are all possible ways to foster shared decision making.

Reforming provider payment. Despite the desire of many to provide more-accountable, better-coordinated and higher-quality care, the existing fee-for-service payment system makes it difficult for hospitals and physicians to integrate care processes because those efforts will often result in lower revenue. Examples include less diagnostic imaging for low-back pain or a choice by some patients of equally effective medical over surgical interventions for particular preference-sensitive conditions.

Rewarding health care systems that engage their providers and patients in shared decision making for preference-sensitive conditions could help reduce the financial incentives pushing increasingly aligned hospitals and physicians to deliver large volumes of less-evidence-based services. This could help reorient hospitals and physicians from increasing their ownership and delivery of specialty services, focusing them instead on delivering patient-centered, evidence-based care. Moving away from fee-for-service payment potentially also could make SDM more attractive to providers who may embrace it as a tool to reduce unnecessary services. Shared decision making could help bridge the gap between old and new payment systems by focusing clinical care on patients’ needs.

Bundled payment, medical homes and ACOs all have the potential to encourage SDM if it is a capability expected of these models. For example, ACOs might be required to demonstrate SDM capabilities among relevant staff, access to a PDA library for their providers and patients, and support for providers to engage patients in SDM for particular preference-sensitive conditions. Such SDM models—for example, Group Health Cooperative—exist and could inform future ACO development.

Integrating SDM into care delivery. Key to integrating shared decision making into care delivery will be determining the most effective ways to engage providers and patients in SDM—for example, identifying when patients are most receptive to using a PDA or how to embed SDM into clinical workflows. For some preference-sensitive conditions, more work is required to better understand how SDM can be tailored to particular clinical settings—primary care vs. specialty care—and which types of providers are best suited for particular SDM roles.32 The lack of complete knowledge on how to most effectively implement SDM for all preference-sensitive conditions need not hinder current efforts to promote SDM for conditions where extensive research exists.

Harnessing health information technology. Health information technology can serve as a catalyst to engage providers and patients in shared decision making. Policy makers are encouraging the adoption and so-called meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs) and other clinical technology through incentives. The meaningful-use criteria address elements of shared decision making in a variety of ways. For example, one facet of meaningful use requires physicians to use clinical-decision-support tools, which in the case of certain preference-sensitive conditions could trigger discussion of shared decision making at the point of care. Also, meaningful-use criteria initially require 50 percent of patients aged 65 and older to have an advance directive recorded in their EHR—rising to 90 percent of such patients over time. Standard shared-decision-making tools focused on end-of-life-care options could support providers in discussing advance directives with patients.

Additional ways that meaningful-use measures could support SDM include giving providers the ability to prescribe SDM via EHRs. Thus, much like a clinician can prescribe medications, a provider could prescribe the delivery of a certified, evidence-based patient-decision aid to patients. At Massachusetts General Hospital, providers already prescribe patient-decision aids, which are then delivered in various modes to patients, including print, Web-based or audiovisual media.33 Meaningful-use standards also could incorporate reminders to use shared decision making. For example, when ordering services where data on effectiveness are mixed, such as a PSA test or advanced imaging for low-back pain, the clinician might be prompted to access a relevant patient-decision aid. To avoid provider-reminder burnout and maximize their utility, such prompts would need to be restricted to screening tests or interventions that are most clearly preference-sensitive.

Empowering Patients

At a time when the U.S. health system is on the brink of broad coverage expansions and many experiments to reform provider payment, a window of opportunity exists to make better-informed and engaged patients a defining aspect of a reformed health system.

Rewarding clinicians who engage their patients in shared decision making could help prevent increasingly aligned hospitals and physicians from simply delivering larger volumes of services. It could also help orient new models of care delivery to patients’ needs. Shared decision making could be a vehicle to help bridge the gap between old and new payment systems by making patient care more focused on patients’ needs and preferences and evidence of treatment effectiveness. In the process, patients could become empowered to make more informed and satisfying health care decisions.

Notes

1. AARP, Building a Sustainable Future: A Framework for Health Security, Washington, D.C. (Annual Report 2008); and Moulton, Benjamin, and Jaime S. King, “Aligning Ethics with Medical Decision-Making: The Quest for Informed Patient Choice,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Spring 2010).

2. Campaign for Effective Patient Care (CEPC), Perception vs. Reality: Evidence-Based Medicine, California Voters, and the Implications for Health Care Reform, survey commissioned by CEPC and fielded by Lake Research.

3. Alexander, G. Caleb, Lawrence P. Casalino and David O. Meltzer, “Patient-Physician Communication about Out-of-Pocket Costs,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 290, No. 7 (Aug. 20, 2003).

4. Zikmund-Fisher, Brian J., et al., “Deficits and Variations in Patients’ Experience with Making 9 Common Medical Decisions: The DECISIONS Survey,” Medical Decision Making, Vol. 30, No. 5 (Supplement) (September/October 2010).

5. Braddock, Clarence H., et al., “Informed Decision Making in Outpatient Practice: Time to Get Back to Basics,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 282, No. 24 (Dec. 22, 1999).

6. Teno, Joan M., et al., “Medical Care Inconsistent with Patients’ Treatment Goals: Association with 1-Year Medicare Resource Use and Survival,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Vol. 50, No. 3 (March 2002).

7. Covinsky, Kenneth E., et al., “Communication and Decision-Making in Seriously Ill Patients: Findings of the SUPPORT Project: The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Vol. 48, No. 5 (Supplement) (May 2000).

8. Wennberg, John E., Elliot S. Fisher and Jonathan Skinner, “Geography and the Debate Over Medicare Reform,” Health Affairs, Web exclusive (Feb. 13, 2002); Brownlee, Shannon, Overtreated: Why Too Much Medicine Is Making Us Sicker and Poorer, New York: Bloomsbury (2007); and Institute of Medicine, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, Washington, D.C. (March 2001).

9. Bentley, Tanya G. K., et al., “Waste in the U.S. Health Care System: A Conceptual Framework,” The Milbank Quarterly, Vol. 86, No. 4 (December 2008); and Wennberg, John E., et al., “Extending the P4P Agenda, Part 1: How Medicare Can Improve Patient Decision Making and Reduce Unnecessary Care,” Health Affairs, Vol. 26, No. 6 (November/December 2007).

10. Charles, Cathy, Amiram Gafni and Tim Whelan, “Shared Decision-Making in the Medical Encounter: What Does it Mean? (Or, it Takes at Least Two to Tango),” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 44, No. 5 (March 1997).

11. U.S. Government Printing Office, President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical Behavioral Research: Making Health Care Decisions, Washington, D.C. (1982); Engel, George L., “The Clinical Application of the Biopsychosocial Model,” American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 137, No. 5 (May 1980); Levenstein, Joseph H., “The Patient-Centered General Practice Consultation,” South African Family Practice, Vol. 5 (1984); Wennberg, John E., “Improving the Medical Decision-Making Process,” Health Affairs, Vol. 7, No. 1 (February 1988); and Sox Jr., Harold C., et al., Medical Decision Making, Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann (1988).

12. Woolf, Steven H., et al., “Promoting Informed Choice: Transforming Health Care to Dispense Knowledge for Decision Making,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 143, No. 4 (Aug. 16, 2005); and Edwards, Adrian, and Glynn Elwyn, 2009 Shared Decision Making in Health Care: Achieving Evidence-Based Patient Choice, 2nd ed., New York: Oxford University Press (2009).

13. Braddock, Clarence H., “The Emerging Importance and Relevance of Shared Decision Making in Clinical Practice,” Medical Decision Making, Vol. 30, No. 5 (Supplement) (September/October 2010).

14. O’Connor, Annette M., et al., “Decision Aids for People Facing Health Treatment or Screening Decisions,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, No. 3 (July 8, 2009).

15. Ibid.

16. Hammes, Bernard J., Brenda L. Rooney and Jacob D. Gundrum, “A Comparative, Retrospective, Observational Study of the Prevalence, Availability, and Specificity of Advance Care Plans in a County that Implemented an Advance Care Planning Microsystem,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Vol. 58, No. 7 (July 2010).

17. L gar , France, et al., “Interventions for Improving the Adoption of Shared Decision Making by Healthcare Professionals,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, No. 5 (May 12, 2010).

18. Merenstein, Daniel, “A Piece of My Mind: Winners and Losers,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 291, No 1 (Jan. 7, 2004).

19. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Public Law No. 111-148, Section 3506.

20. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), Shared Decision Making and its Implications for Medicare, MedPAC’s Report to Congress: Aligning Incentives in Medicare, Washington, D.C. (June 2010); and Schoen, Cathy, et al., Bending the Curve: Options for Achieving Savings and Improving Value in U.S. Health Spending, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, N.Y. (December 2007).

21. Sepucha, Karen, and Albert G. Mulley, Jr., “A Perspective on the Patient’s Role in Treatment Decisions,” Medical Care Research and Review, Vol. 66, No. 1 (Supplement) (February 2009).

22. Wennberg (November/December 2007).

23. Yedidia, Michael J., et al., “Effect of Communications Training on Medical Student Performance,” Journal of the American Medical Association,Vol. 290, No. 9 (Sept. 3, 2003); Towle, Angela, and Joanne Hoffman, “An Advanced Communication Skills Course for Fourth-Year, Post-Clerkship Students,” Academic Medicine, Vol. 77, No.11 (November 2002); and L gar , France, et al., “Effective Continuing Professional Development for Translating Shared Decision Making in Primary Care: A Study Protocol,” Implementation Science, Vol. 5, No. 83 (Oct. 27, 2010). See also http://decision.chaire.fmed.ulaval.ca/index.php?id=180&L=2 (L gar ’s website listing SDM programs for health professionals.)

24. L gar (Oct. 27, 2010).

25. Zickmund-Fisher (September/October 2010).

26. Merenstein (January 2004).

27. Center for Advancing Health, Snapshot of People’s Engagement in their Healthcare, Washington, D.C. (May 20, 2010).

28. Chernew, Michael E., Allison B. Rosen and A. Mark Fendrick, “Value-Based Insurance Design,” Health Affairs, Vol. 26, No. 2 (March/April 2007).

29. Chesser, Amy K., et al., “Prescribing Information Therapy: Opportunity for Improved Physician-Patient Communication and Patient Health Literacy,” Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, Online First (Aug. 5, 2011).

30. Pear, Robert, “U.S. Alters Rule on Paying for End-of-Life Planning,” The New York Times (Jan. 4, 2011).

31. Carman, Kristin L., et al., “Evidence that Consumers are Skeptical about Evidence-Based Health Care,” Health Affairs, Vol. 29, No. 7 (July 2010).

32. Woolf (Aug. 16, 2005).

33. Kemper, Donald W., and Molly Mettler, Information Therapy: Prescribed Information as a Reimbursable Medical Expense, Center for Information Therapy, Washington, D.C. (April 4, 2002).

Data Source

This work is based on a literature review, the authors’ collective clinical and policy experience, and information from in-depth interviews with 10 experts working in the areas of health policy, shared decision making, patient-decision aids, health care reform, clinical care and medical education.

About the Authors

Ann S. O’Malley, M.D., M.P.H., is a senior researcher at the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC); Emily R. Carrier, M.D., M.S.C.I., is a senior researcher at HSC; Elizabeth Docteur, M.S., formerly of HSC, is an independent consultant; Alison C. Shmerling is a former HSC research assistant; and Eugene C. Rich, M.D., is a senior fellow and director of the Center on Health Care Effectiveness at Mathematica Policy Research.