While there is little debate about a growing primary care workforce shortage in the United States, precise estimates of current and projected need vary. A secondary problem contributing to addressing capacity shortfalls is that the distribution of primary care practitioners often is mismatched with patient needs. For example, patients in rural areas or low-income patients—particularly the uninsured—may have greater problems accessing primary care services than well-insured, suburban residents. Most efforts to improve access to primary care services center on increasing the supply of practitioners through training, educational loan forgiveness or scholarships, credentialing, and higher payment rates. The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) includes many provisions promoting these strategies. While existing, longer-term efforts to boost the primary care workforce are necessary, they may be insufficient for some time because a meaningful increase in practitioners will take decades. Rather, policy makers may want to consider ways to increase the productivity of primary care providers and accelerate primary care workforce expansion by, for example, examining how changes in state scope-of-practice policies might increase the supply of non-physician practitioners

- Primary Care Access Problems Likely to Grow

- Increasing Primary Care Capacity

- Other Policy Options

- Looking Ahead

- Notes

- Data Source

Primary Care Access Problems Likely to Grow

The current and likely growing undersupply of primary care practitioners in the United States is a focus of both state and national policy makers, particularly as overall population growth and aging, coupled with coverage expansions under health reform, will accelerate demand for primary care in the coming years. Collectively, an estimated 400,000 practitioners, including physicians—both allopathic and osteopathic—advanced practice nurses (APNs) and physician assistants (PAs), provide primary care in the United States.1 Primary care physicians are typically categorized as those with postgraduate medical training in family medicine, pediatrics or internal medicine.

Estimates of primary care shortages vary, reflecting differences in data collection and measurement, but most national studies indicate that while the supply of primary care practitioners is increasing, it is neither sufficient for current needs nor keeping pace with demand. To meet a target of one provider for every 2,000 patients, the Health Resources and Services Administration estimates that an additional 17,722 primary care practitioners are already needed in shortage areas across the country. Further, an analysis of the aging U.S. population found that another 35,000 to 44,000 adult primary care providers may be needed by 2025.2

Though the health reform law includes measures to address the recognized shortage, other provisions in the law likely will increase demand for primary care. For example, the law is expected to extend coverage to an estimated 32 million uninsured people by 2019, which will increase demand for primary care services. Overall, the PPACA coverage expansions are predicted to increase the shortage of primary care physicians from approximately 25,000 to 45,000 by 2020.3

Demand from newly covered people will be unevenly distributed across the country. Research indicates that states expecting the largest percentage increases in Medicaid enrollees under coverage expansions tend to have relatively low supplies of primary care physicians, despite having relatively high Medicaid payment rates. Primary care physician shortages are higher in states with fewer urban areas; the rural/urban variation appears to have more influence on overall primary care physician supply than Medicaid payment rates and physician willingness to accept Medicaid patients. Thus, the Medicaid payment rate increases implemented through PPACA are projected to have less impact in states that have a relatively low supply of primary care physicians.4

At the same time, the health reform law encourages new, primary-care-centered models of care delivery to help control health care costs, in part by encouraging patients to use more primary care and preventive services in place of costlier specialty care. Such delivery system reforms, including wider adoption of patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), may further stretch the primary care workforce. With these concurrent factors at work, approaches beyond those in the PPACA likely are needed to generate adequate primary care capacity in the health system.

Increasing Primary Care Capacity

Policies included in PPACA attempt to address both short-term and long-term elements of primary care workforce capacity. For example, temporary payment rate increases for primary care services may encourage providers to see more patients and deliver more services, increasing their capacity in the short run. Other policies, such as increased funding for loan forgiveness for clinicians willing to work in underserved areas, may attract more practitioners to primary care, increasing total supply in the longer run. The main thrust of PPACA policies to expand primary care workforce capacity include (see Table 1 for more details on PPACA provisions):

- increasing the number of trainees who are likely to pursue careers in primary care;

- encouraging graduates to practice primary care, particularly in underserved geographic areas; and

- adding to the skills of practitioners already working in primary care.

While each of these approaches has the potential to be beneficial, the benefit may not be large—or immediate. In addition, these strategies have undergone only limited evaluation as stand-alone programs and none in combination. For example, the health reform law includes temporary Medicare and Medicaid payment rate increases for primary care services, but how this policy will affect access and delivery is largely unknown. In addition, performance-based incentives for providing high-quality, coordinated care supported by health information technology also could increase overall payment for primary care, but these advances will require substantial investment of time and money by providers.

Even if PPACA policies are highly effective in bringing new practitioners into the workforce, they may be insufficient given the timeline to train new physicians and other primary care practitioners (see box below for more about training requirements for primary care practitioners). Currently, about 300,000 physicians practice primary care and about 3,000 new U.S.-educated physicians enter primary care each year, adding about 1 percent to the primary care physician workforce annually.8 (This is not a net gain of physicians, as it does not take into account physicians exiting the workforce.) If the cumulative effect of PPACA provisions increased the annual number of new primary care physicians by 20 percent—an optimistic assumption—new U.S.-educated physicians would generate an additional 0.3 percent of the primary care physician workforce, or about 600 additional physicians, annually. Under this scenario, by 2020, a decade after the passage of health reform, an estimated 6,000 new physicians would enter the primary care workforce, still well under the American Association of Medical Colleges’ (AAMC) predicted need of about 45,000 primary care physicians.

Table 1

|

||

Policy |

Description |

Potential Impact |

| Payment Reform | Designated primary care practitioners receive a 10 percent Medicare bonus payment (effective 2011-15); Medicaid payment rates for specific primary care services provided by primary care physicians increased to at least equal Medicare levels (effective 2013-14). | Some modeling suggests higher payment rates can increase the quantity of primary care services provided; however, a temporary increase may have less impact. |

| Care Delivery Reforms and Pilot Programs | Medicare Shared Savings/accountable care organizations (ACO) Program; community health teams to support patient-centered medical homes. | Health care organizations, such as ACOs, may encourage development of team-based primary care practices to increase capacity and improve efficiency. |

| Support Primary Care Training in Academic Settings | Awards grants to plan, develop and operate training programs in primary care; provides financial assistance to trainees and faculty; enhances faculty development in primary care and physician assistant programs. | Students recruited through targeted training programs are more likely to enter primary care in underserved areas. However, such programs may require large investment with a relatively small yield. Also, if residency slots are fixed, increases in U.S. graduates may merely displace international graduates, resulting in minimal impact on the net primary care workforce. |

| Creating New Primary Care Residency Programs | Redistributes residency positions in case of vacancies, and mandates 75 percent of new Medicare-supported residencies be in primary care, including internal medicine; academic medical centers or teaching hospitals may obtain grants for primary care residency programs. | Focusing on residency programs historically has a higher yield than creating academic training programs. Residents can also provide patient care and generate revenue for hospitals during their training. |

| Scholarships for Students Planning to Practice Primary Care | Grants to medical schools to recruit students likely to practice in rural areas; grants to train residents in preventive medicine specialties. | Students who are more likely to practice primary care, particularly in underserved areas, are also likely to face financial barriers to obtaining medical training; scholarships can address this barrier. |

| Loan Forgiveness and Direct Financial Incentives for Primary Care Practicioners | Increases annual and aggregate maximum on loans for nurses; increase in National Health Service Corps scholarships and loan forgiveness funding for primary care practitioners that practice in shortage areas. | Relative to scholarships, loan forgiveness has much lower dropout rates, higher retention and satisfaction. |

| Source: Authors’ analysis of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act | ||

The Primary Care Pipeline

U.S. primary care practitioners enter the workforce with varied training requirements, affecting their supply as well as the services they can provide. The length of time to train a primary care practitioner, as well as the availability and cost of their training, affects the viability of strategies aimed at increasing the supply of primary care practitioners.

U.S.-trained allopathic (M.D.) and osteopathic (D.O.) physicians enter the primary care workforce after receiving a college degree, graduating from an accredited medical school, and completing a postgraduate residency in family practice, internal medicine or pediatrics, usually lasting three years. During residency training, these U.S.-trained physicians are joined by international medical graduates, who either are born in the United States or elsewhere but attended medical school outside the United States or Canada. International medical graduates have for decades propped up the U.S. primary care supply and now comprise nearly a quarter of all primary care physicians.5

After completing residency training, physicians may elect to work full time or part time. An estimated 300,000 primary-care-trained physicians practice in the United States.6 Other physicians complete additional training in subspecialties but continue to provide primary care services for some or all of their patients; the amount and comprehensiveness of primary care services provided by specialists is difficult to estimate.

Non-physician practitioners also provide primary care services, both independently and under physician supervision. Advanced practice nurses can evaluate and treat patients independently or work under physician supervision, depending on state scope-of-practice laws. Physician assistants in all states must work under physician supervision, but most PAs work with specialist physicians. Some studies estimate that APNs can provide 80 percent of the care currently provided by primary care physicians.7 APNs are baccalaureate-prepared registered nurses who have completed at least two years of graduate-level education and an additional year of clinical training before they are eligible to be licensed by the state where they practice. Typically, PAs are required to complete two years of post-baccalaureate training, and all are required to pass a national certification exam to enter clinical practice, in addition to being licensed by the state where they practice. PAs are not required to have graduate-level education, though almost half of practicing PAs do. An estimated 80,000 APNs and 20,000 PAs are currently practicing primary care in the United States.

Other Policy Options

The impact of current policies to expand primary care capacity could be bolstered by complementary approaches that could take effect more rapidly to meet expected jumps in demand. Other approaches that policy makers might consider include:

- expanding state scope-of-practice laws; and

- adopting payment policies that foster increased productivity of primary care practitioners.

Expanding Scope of Practice

Given the supply of advanced practice nurses currently delivering primary care and the shorter time frame required for training new entrants, broadening scope-of-practice laws for APNs is a possible avenue to expand primary care capacity more rapidly. State scope-of-practice laws, which determine the tasks non-physician health professionals can perform and the extent to which they may work independently, vary widely. Changing these laws is a highly politicized process and has generated considerable controversy among APNs and physicians.

Evidence of primary care shortages appears to be shifting the debate in some states on scope-of-practice laws. Massachusetts, where APNs may not practice independently, experienced increased shortages of primary care practitioners after state enactment of near-universal health coverage in 2006.9 Legislation has been introduced but not enacted to expand the state’s scope-of-practice regulations; one bill focuses specifically on primary care. Legislation, citing a shortage of practitioners in many counties, also has been introduced in Michigan to expand the scope of practice for APNs.10

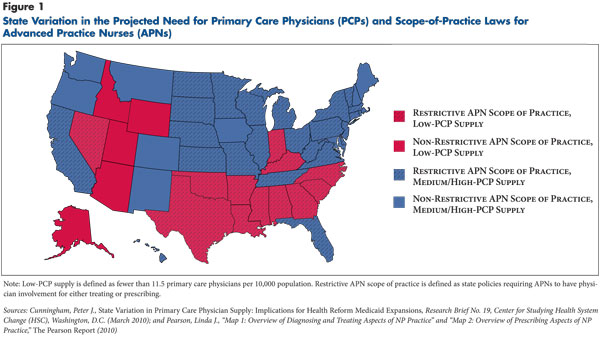

Other states’ impetus to reexamine scope-of-practice policies likely will vary depending on their primary care capacity and distribution of practitioners. Currently, 22 states and the District of Columbia permit APNs to practice independently, while others require some level of physician oversight.11 Two-thirds of states with a shortage of primary care physicians also have restrictive scope-of-practice laws, which may be a barrier to increasing access to primary care services through APNs (see Figure 1).

Not surprisingly, advanced practice nurses and physicians strongly disagree about which professionals are qualified to perform what tasks. While multiple studies show that APNs’ performance on such quality measures as delivery of recommended preventive services, patient satisfaction and short term mortality are at least equal to that of physicians, these measures represent only a subset of primary care competencies.12 Different patients have different needs, and little is known about what types of patients would benefit more from the experience and skill set associated with physician training and which would benefit equally well or more from the experience and skill set of APNs. The size and resources of the practice, as well as the preferences of providers themselves, also may play a role in determining who should perform what tasks for particular patients.

While state policy makers have jurisdiction over scope-of-practice laws, federal policy makers also can play a role. One option at the federal level is to offer more direct funding to states that allow APNs to practice independently. The PPACA allocates $50 million annually from 2012-15 for hospitals to train APNs, along with other provisions allowing increased use of APNs in primary care. For example, the Medicare Shared Savings Program for accountable care organizations (ACOs) recognizes APNs as primary care practitioners, though these regulations defer to state scope-of-practice policies.13 An Institute of Medicine (IOM) panel recently recommended that states expand APNs’ scope of practice in primary care.14 According to an AAMC estimate projecting primary care physician need in 2025, if APNs and PAs were given expanded roles that reduced the need for primary care physicians by 25 percent, demand would decrease by approximately 75,100 full-time-equivalent physicians. Under this scenario, another 150,000 APNs or PAs would be required by 2025.

Payment Policies for Team-Based Care

Changing the way practitioners are paid can have an immediate effect on the amount and type of care they deliver. A variety of payment methods beyond those enacted by the health reform law can potentially augment primary care capacity. These methods, such as capitated payments that put providers at risk for the cost of care or case management models that provide additional payments for care management, may incentivize and encourage the development of teams that share care responsibilities. These teams potentially can deliver more primary care to a greater number of patients than a physician working alone could provide, though there are concerns about physician satisfaction and whether team-based care truly increases efficiency.

Alternative care delivery models involve health professionals beyond physicians—for example, nurses, social workers and others—in care coordination and other patient care tasks. In some team-based models, caregivers work as part of a larger group under the supervision of a physician, who maintains legal responsibility for the group. Advocates of these models have emphasized their positive impact on quality of care and patient satisfaction. However, it is important to note that the short term effect on primary care capacity will depend mostly on the degree to which lead practitioners can delegate tasks to others.

Primary care practices that implement team-based models also may be more likely to adopt other modifications that will affect primary care practitioner productivity. For example, supplementing traditional office visits with email and telephone visits may allow primary care practitioners to have personal interactions with more patients. Other approaches, such as care coordination agreements, allow primary care practitioners to initiate care that would previously have been performed by specialists. These agreements may fulfill such important policy goals as diminishing care fragmentation and encouraging care delivery in the lowest-cost setting possible, but they may also create additional responsibilities for busy primary care practitioners.

Despite their promise, there is no guarantee that team-based care models will automatically increase population-level access to primary care. In the short term, these models may have the opposite effect. Many pioneers of team-based care have been motivated by improving care coordination and quality rather than stretching the primary care clinician supply. In fact, several successful PCMH programs have reduced physician patient-panel size. For example, Group Health’s initiative15 reduced physician panels from an average of 2,327 patients to 1,800. The PCMH run by the Veterans Health Administration, likewise, decreased physician panel size to about 1,000 to 1,100 patients from 1,200.

However, PCMH proponents believe that team-based care will ultimately increase primary care physician satisfaction and lead to an increase in the number of new medical residents specializing in primary care. Whether these gains are realized may depend on how providers implement team-based care. Presumably, under reformed payment policies, a team-based approach designed to increase the productivity of primary care clinicians will lead to higher incomes for participating practitioners, which also could encourage more to enter the field. However, government or philanthropic support may be needed to fund development of such models. State policy makers will have considerable influence over access to and payment for primary care, given the estimated 16 million people that will gain Medicaid coverage by 2019.

Looking Ahead

The approaches to expanding primary care supply included in the PPACA are generally noncontroversial, but it may be a decade or more before their full impact on primary care supply is realized. Even if successful, policy makers will be hard-pressed to continue this investment in the coming years. Notably, the shortage of primary care capacity can be traced back in part to previous volatility in policy support for primary care, when Medicare legislation in the1980s raised payments for primary care, but an inadequate updating process eroded those gains over time, particularly for evaluation and management services.

Policy makers also may want to consider the consequences of capping the number of graduate medical education (GME) residencies and reducing Medicare GME funding. Constraining residency slots might preclude longer-term policies for increasing the supply of primary care physicians. The Council on Graduate Medical Education has recommended increasing residencies in selected specialties with shortages, such as adult primary care and psychiatry. Similarly, the National Health Service Corps (NHSC) currently offers loan repayment to primary care practitioners working in designated health professional shortage areas. Participation in NHSC programs has roughly tripled since 2008 because of increased funding. Such targeted efforts may better align distribution of providers with need, both geographically and by specialty.

Nonetheless, increasing primary care supply in the short and medium term may prove a challenging task. In the current fiscal environment, increasing primary care compensation relative to specialists to levels that have successfully changed the population of practitioners in other nations is unlikely. In addition, unquantifiable factors, such as culture, status and professional identity may play as great a role as payment in determining where and how clinicians provide care. Policy makers may wish to consider how they can address these less-tangible barriers to building primary care supply. For example, opportunities to enhance supply may mean training practitioners to become more comfortable with delegation and larger patient panels.

In the meantime, examining scope-of-practice laws and payment reforms to increase productivity of primary care practices may have a greater near-term impact on primary care supply and also increase the effectiveness of longer-term measures included in health reform.

Notes

1. Dower, Catherine, and Edward O’Neill, Primary Care Health Workforce in the United States, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, N.J. (July 2011); Bodenheimer, Thomas, and Hoangmai H. Pham, “Primary Care: Current Problems and Proposed Solutions,” Health Affairs, Vol. 29, No. 5 (May 2010).

2. Staiger, Douglas O., David I. Auerbach and Peter I. Buerhaus, “Comparison of Physician Workforce Estimates and Supply Projections,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 302, No. 15 (Oct. 21, 2009); U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, The Physician Workforce: Projections and Research into Current Issues Affecting Supply and Demand, Washington, D.C. (December 2008); Council on Graduate Medical Education, HRSA, Sixteenth Report: Physician Workforce Policy Guidelines for the United States, 2000-2020, Washington, D.C. (January 2005); and Colwill, Jack M., James M. Cultice and Robin L. Kruse, “Will Generalist Physician Supply Meet Demands of an Increasing and Aging Population?” Health Affairs, Vol. 27, No. 3 (May/June 2008).

3. Kirch, Darrell G., Mackenzie K. Henderson and Michael J. Dill, “Physician Workforce Projections in an Era of Reform,” forthcoming in Annual Review of Medicine; and Dill, Michael J., and Edward S. Salsberg, The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections Through 2025, Center for Workforce Studies, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), Washington, D.C. (November 2008).

4. Cunningham, Peter J., State Variation in Primary Care Physician Supply: Implications for Health Reform Medicaid Expansions, Research Brief No. 19, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (March 2010).

5. Boukus, Ellyn R., Alwyn Cassil and Ann O’Malley, A Snapshot of U.S. Physicians: Key Findings from the 2008 Health Tracking Physician Survey, Data Bulletin No. 35, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (September 2009).

6. Bodenheimer and Pham (2010).

7. Institute of Medicine, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health, National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. (2010).

8. AAMC reports on the national residency match consider all medical school graduates matching into internal medicine, family practice or pediatrics as primary care providers. AAMC does not include geriatrics in its primary care estimates given the small number of residency matches, though they are ostensibly considered to be primary care practitioners. This analysis takes into account that about 44 percent of these graduates will go on to specialize rather than remain in primary care. However, it assumes that all new entrants to primary care will participate in full-time clinical care and none of them will displace foreign-educated primary care physicians, both of which are optimistic assumptions.

9. Massachusetts Medical Society, Physician Workforce Study, Boston (September 2009).

10. Massachusetts Bill H.1520, 187th General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (2011); and Michigan House Bill 4774 and Senate Bill 481, 96th Legislature (2011).

11. Pearson, Linda J., “Map 1: Overview Of Diagnosing and Treating Aspects of NP Practice” and “Map 2: Overview of Prescribing Aspects of NP Practice,” The Pearson Report (2010).

12. Wilson, Jennifer F., “Primary Care Delivery Changes as Non-Physician Clinicians Gain Independence,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 149, No. 8 (Oct. 21, 2008).

13. Medicare Shared Savings Program: Accountable Care Organizations, Final Rule, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (Nov. 2, 2011).

14. Institute of Medicine (2010).

15. Reid, Robert J., et al., “Patient-Centered Medical Home Demonstration: A Prospective, Quasi-Experimental, Before and After Evaluation,” American Journal of Managed Care, Vol. 15, No. 9 (September 2009).

Data Source

This analysis is based on a literature review focusing on the primary care workforce composition, projected shortage and policies related to addressing these issues. Policy options were analyzed based on data from various sources describing the primary care supply, projected demand and relevant legislation, as well as the authors’ collective clinical and policy experience.