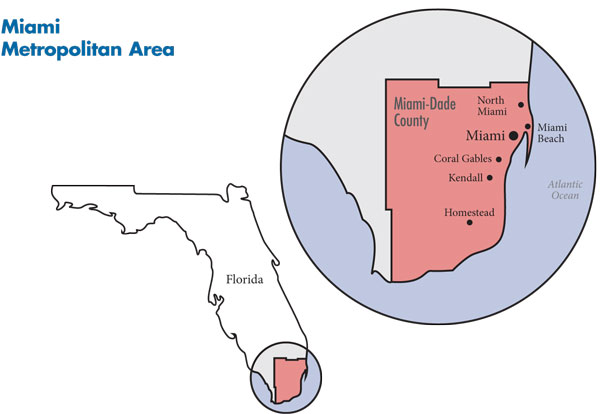

In September 2010, a team of researchers from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), as part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS), visited Miami to study how health care is organized, financed and delivered in that community. Researchers interviewed more than 45 health care leaders, including representatives of major hospital systems, physician groups, insurers, employers, benefits consultants, community health centers, state and local health agencies, and others. The Miami metropolitan area comprises the same borders as Miami-Dade County.

The economic downturn and disproportionate fallout on the tourism, real estate and construction sectors have affected Miami more severely than many metropolitan areas across the country. Unemployment doubled and many small firms closed or dropped health coverage for workers. While almost a third of Miami residents are uninsured, the Miami safety net is struggling because of Jackson Health System’s financial troubles.

Numerous health plans and providers serve the Miami market. Insurers are competing to offer new products—and revisiting old ones—to gain enrollees. Baptist Health South Florida and the other main hospital systems are expanding geographically in search of well-insured patients. The community is served by a relatively large number of physicians who remain largely independent in small primary care or consolidating specialty practices, yet some are exploring tighter affiliations with hospitals.

Key developments include:

- Hospital systems are redefining their geographic service areas, and competition among hospital systems is increasing as they acquire or add facilities in areas beyond their traditional markets.

- Health plans are developing lower-cost, limited-benefit products to serve the growing, price-sensitive individual insurance market and to forestall further decline of the small-group market.

- Jackson Health System, the area’s largest safety net provider, is struggling financially, which, coupled with a lack of coordination among safety net providers, undermines the community’s ability to respond to the prolonged economic downturn.

- A Diverse, Struggling Community

- Hospitals Expand Geographically

- Physicians Largely Remain Independent

- Health Plans Try to Retain Small Groups

- Safety Net in Distress

- Fledgling Efforts to Coordinate Safety Net

- Medicaid Feared Unsustainable

- Anticipating Health Reform

- Issues to Track

- Background Data and Funding Acknowledgement

A Diverse, Struggling Community

While commonly viewed as a wealthy tourist destination, the Miami metropolitan area (see map below) is home to many people facing significant financial hardship. Miami residents are more likely to earn lower incomes or be unemployed than residents in other large metropolitan areas; indeed, Miami’s unemployment rate stood at 13.1 percent in September 2010 vs. an average of 9.4 percent across large metropolitan areas. Almost a third of Miami’s 2.5 million residents lack health insurance—significantly higher than the 15.1 percent average across large metropolitan areas in 2009.

In part, these trends reflect the community’s large immigrant population. Making up almost two-thirds of the population, Latinos comprise a much larger proportion of the population than in many other metropolitan areas. About half of Miami residents were born outside the United States, and about a third have limited English-speaking abilities.

In addition, the tourism and construction industries critical to the Miami economy were hit hard by the economic downturn, with corresponding fallout on small employers. The Miami area has a relatively large proportion of small firms, although market observers reported that many small businesses closed in recent years.

Still, wealth varies across Miami-Dade County. The northern and western areas are generally home to middle-income people but also have pockets of affluence and poverty. The southern suburbs, including Coral Gables, are home to higher-income people. Kendall is a growing community in the southwestern part of the county and is home to many middle-income, insured residents. Central Miami and the far southern, more rural parts of the county are typically lower income. Miami Beach, separated from the city of Miami by Biscayne Bay and accessible by a series of causeways, historically had an older, more-affluent population but is becoming younger and more diverse.

Back to Top

Hospitals Expand Geographically

Anumber of hospital systems and independent hospitals serve the Miami market, including Baptist Health South Florida, HCA East Florida, Tenet Healthcare Corp., Mt. Sinai Medical Center and UHealth, the University of Miami system. Largely staffed by UHealth physicians, the county-owned Jackson Health System is the major provider of inpatient care to Miami’s low-income residents and provides specialized services—including trauma care, burn care and organ transplants—to the entire community.

Historically, Miami has been a geographically segmented hospital market, with systems facing little competition within their own neighborhoods. Baptist Health South Florida, a nonprofit system with five acute care hospitals dominating southern Miami-Dade County, remains the market leader, particularly for well-insured people, with approximately 20 percent of inpatient admissions. For-profit HCA and Tenet Healthcare Corp. dominate northern and western Miami-Dade. HCA has two acute care hospitals, and its purchase of Mercy Hospital will give it a renewed presence in central Miami-Dade as well. Tenet South Florida has four acute care hospitals. Mt. Sinai Medical Center, a nonprofit teaching hospital, is the largest stand-alone facility in the market with more than 700 beds and is the only hospital on Miami Beach.

Jackson Health System, with one main hospital campus and two satellites, is publicly owned and supported. The system is financed and managed by Miami-Dade County’s Public Health Trust, an independent governing body that reports to the Board of County Commissioners. Although the system provides more than 20 percent of inpatient admissions in the market, a majority of admissions are uninsured and Medicaid patients, making Jackson less of a competitor to other hospitals. Jackson Memorial Hospital, the largest hospital in the Jackson system, is in central Miami, near downtown, and co-located with Holtz Children’s Hospital and Jackson Rehabilitation Hospital. Jackson also operates satellite hospitals in both the northern and southern suburban areas of the county.

Miami hospitals suffered financially to varying degrees during the economic downturn with related increases in uncompensated care costs, as well as reports of reductions in elective procedures and imaging. Hospitals with leverage to negotiate higher private insurer payment rates, because they are located in relatively well-insured neighborhoods and have lucrative specialty-service lines, emerged with positive margins, although not without adopting cost-cutting measures. Namely, Baptist benefits from its location in relatively affluent southern Miami-Dade and remains financially strong, while largely inner-city Jackson struggles.

In addition, hospitals are attempting to shore up revenues by strengthening profitable specialty-service lines. For instance, Tenet established new neurology and spine service lines, while Mt. Sinai has increased capacity in cardiology and urology. Mt. Sinai recently hired a prominent cardiologist who previously practiced at Baptist and brought a significant number of new patients to Mt. Sinai.

To attract and retain more privately insured patients, some Miami hospitals are expanding beyond their traditional geographic market areas. In 2007, the University of Miami Health System (UHealth) acquired Cedars Medical Center, a 560-bed community hospital—now University of Miami Hospital—across the street from Jackson Memorial Hospital. This created a community hospital alternative for insured patients who might want to seek primary and some tertiary services from UHealth physicians but are reluctant to use the public Jackson facilities, which UHealth physicians also staff. Most respondents agreed the UHealth hospital acquisition has shifted some privately insured patients away from Jackson.

In addition, the Kendall area is becoming a hotbed of competition between southern and northern Miami-Dade systems: Baptist’s new West Kendall Baptist Hospital, which opened in April 2011, is close to HCA’s Kendall Regional Medical Center. Kendall Regional Medical Center recently announced plans to establish a Level 2 trauma center, triggering complaints from the university and Jackson that the new center will siphon off relatively well-insured victims of motor vehicle trauma from nearby highways who otherwise would have gone to Jackson.

Hospitals are expanding outpatient facilities as well. Baptist has increased outpatient capacity with a number of new medical plazas—which include diagnostic and imaging equipment, physician offices, and urgent care centers—to attract insured patients. These new facilities, located to the north in Broward County, have performed well financially, and more are planned. Also, UHealth is establishing an ambulatory care facility at the university’s main campus in Coral Gables, prompting protests from Baptist, according to news media reports, which has held a stronghold in southern Dade.

In keeping with national trends, emergency department (ED) volumes continue to rise in Miami, stimulating competition in this service line as well. The competition is most obvious among facilities in well-insured areas, where ED visits that result in admissions can increase hospital inpatient revenues. Several hospitals advertise their ED wait times on billboards and on the Web and have adopted new ED marketing technologies. HCA provides patients with the ability to receive the location of HCA’s closest facilities and their projected ED wait times on their cellular phones when they text “ER” to a designated number. Baptist and Mt. Sinai have built new EDs in recent years, and in both cases, their ED volumes increased significantly even though they have not advertised heavily. In 2008, Mt. Sinai opened a freestanding ED about one mile from HCA’s Aventura Hospital and Medical Center, north of Miami Beach.

Physicians Largely Remain Independent

Miami has a relatively large number of physicians per capita compared to other metropolitan areas. Physicians in Miami historically have preferred their independence over formally affiliating with other physicians and hospitals. Most primary care physicians in Miami continue to practice in small groups, and primary care physician payment rates reportedly are relatively low. In contrast, physicians in many specialties are consolidating into larger single-specialty practices. However, with the exception of the University of Miami Medical Group with more than 800 physicians, specialty groups generally contain fewer than 50 physicians. Also, some physician groups have invested in ambulatory surgical centers to compete with hospitals.

For years, a significant number of Miami physicians reportedly had dropped or limited their malpractice coverage because of premiums much higher than in other areas. The state responded to physicians’ concerns with a 2003 law allowing physicians to practice without insurance if they hold at least $250,000 in assets. While going without insurance has become common practice for physicians, this may be changing, with reports that malpractice insurers have experienced six consecutive years of profits and 10 new malpractice insurers have entered the Florida market in recent years.

In response to the financial pressures facing independent physicians and expected changes from national health care reform, physicians and hospitals are cautiously exploring ways to work more closely. As one health system leader said, “We know that close affiliation [with physicians will be necessary, but] we’re not sure how to get there.”

Many physicians still admit patients to multiple hospitals, and the actual employment of physicians by hospitals continues to grow more slowly in Miami than in many communities. According to one respondent, relations between hospitals and independent physicians remain “strained, at best,” while another noted that “there is no love” between physicians and hospitals. Some hospital leaders questioned the financial logic of employing physicians, except in the case of subspecialists who offer unique services, such as research leadership and a track record of obtaining prestigious grants, or provide emergency department and on-call coverage.

Back to Top

Health Plans Try to Retain Small Groups

Miami’s largest commercial insurers include UnitedHealth Group, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Florida, Aetna, CIGNA and AvMed, while Humana has a strong presence in the Medicare Advantage market. No plan holds a dominant market share, and the number of plans serving the commercial market has been relatively stable since 2005, following a series of health plan mergers and acquisitions earlier in the decade.

Miami remains a relatively high-cost area for Medicare beneficiaries, with expenditures per beneficiary at about 55 percent above the national metropolitan area average. Respondents speculated that higher Medicare spending may be driven by high rates of fraud and abuse, the market’s relatively large number of specialists and physician practice styles that reflect use of more high-cost specialty services. Still, it is not clear that medical costs for the privately insured are significantly higher in Miami than elsewhere. Even so, Miami employers reportedly have passed on a substantial share of rising costs to employees through increases in patient cost sharing, such as higher deductibles and coinsurance, and employees’ share of premiums.

With the commercial health plan market relatively fragmented among a number of national and regional insurers, the leverage that any one plan has in provider negotiations is limited. In particular, Baptist Health is viewed by health plans as particularly effective at using its strong market position in southern Miami-Dade County to obtain favorable payment rates. While some specialty physicians have gained negotiating leverage by forming larger groups, health plans have more leverage over the primary care physicians in the market.

The national health plans—including United, Aetna and CIGNA—serve employees of national and global firms who reside in Miami, as well as compete for the business of larger, self-insured employers that are headquartered there. Most national plans also compete with regional plans in the small-group and individual insurance markets. However, the health benefit demands of the many small employers in Miami differ from those of large national employers. Because of the economic downturn, small employers reportedly are even more price sensitive than in the past.

Moreover, given economic pressures, health plans are competing for, as one health plan respondent put it, a “smaller pie” of small-group enrollees. In the broader Miami market, including the Fort Lauderdale and Pompano Beach area, national data from the federal Medical Expenditure Panel Survey indicate that the percentage of firms with fewer than 50 employees offering health insurance declined from 41.9 percent in 2002 to 32.8 percent in 2010. Of the 20 largest metropolitan areas in the United States, Miami ranked fifth from the bottom with respect to the percentage of small firms offering health insurance.

Because health plans have been unsuccessful in restraining provider payment rate increases or negotiating innovative payment arrangements, they instead have focused on developing and marketing products with higher deductibles, coinsurance and copayments to retain existing small-group business. Insurers also are beginning to market lower-cost products with more limited hospital networks. The plans hope that these same strategies will increase their ability to compete in the individual health insurance market in Miami, which is growing as small employers drop coverage.

Miami historically has been a strong health maintenance organization (HMO) market. Large employers offer open-access HMO and point of service (POS) plans alongside preferred provider organization (PPO) products, and HMO cost sharing and provider networks are largely indistinguishable from those of PPOs.

Also, among smaller or lower-wage employers, more traditional, restricted-network HMOs seem to be growing in popularity after several years of relatively stagnant enrollment. Neighborhood Health Partnership, a local plan acquired by United, and AvMed are successfully marketing gatekeeper-model HMO products to small and mid-sized employers as lower-cost options to PPOs. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Florida had downplayed its broad network, open-access HMO product in Miami in favor of PPO products but is changing course and trying to rejuvenate its HMO products as more-restrictive, lower-cost options.

In particular, more-restrictive HMO products reportedly appeal to immigrant residents from Central and South America because they prefer the predictability of fixed copayments and are relatively tolerant of restrictions on where they can obtain care. As a market observer explained, “There’s a comfort level within an offering of an HMO. It could be related to the individuals we have here who came to the U.S., and the way they have experienced health care in the past fits into the model.”

Back to Top

Safety Net in Distress

The most significant development facing the Miami safety net is the financial crisis confronting Jackson Health System. Of an annual budget of $2 billion, Jackson lost approximately $240 million in 2009 and $100 million in 2010 and, according to media reports, is projecting a loss of about $85 million in fiscal year 2011. Respondents attributed Jackson’s financial problems to many factors: the recession, which has increased demand for uncompensated care; a decrease in county tax revenues that subsidize the system; new competition from the University of Miami’s acquisition of Cedars Medical Center; past mismanagement; and an ineffective governance structure.

Despite its financial woes, Jackson has not reduced services in a way that has, as yet, had a major negative impact on access to care in the community. Of its six primary care clinics, Jackson closed two, attributed in part to a significant decline in volume at these facilities, and, more recently, lost the contract for a third one, which will continue to serve mainly undocumented immigrants through another physician group. Jackson’s most significant reduction in service was the discontinuation of payment for outpatient dialysis for uninsured patients. While most people affected by this change obtained care through other providers, some have struggled with access to care.

Concerns remain that Jackson’s governance structure hinders hospital management’s ability to address long-term fiscal challenges. Under Jackson’s current governance structure, major changes must be approved by the Board of County Commissioners, which some believe is overly influenced by political considerations. Among the most prominent conclusions by a grand jury convened in 2010 to examine the problems at Jackson was that its administrators and the Public Health Trust lacked the autonomy to take the necessary steps to strengthen Jackson’s finances, including staff reductions, closures of facilities and termination of revenue-losing services. A key example given was Jackson’s attempt to close its obstetrics unit at Jackson South Hospital, which, according to the Public Health Trust, lost $2.5 million in 2009. However, county commissioners rejected this move, arguing that obstetrics was a key function of a public hospital, despite low volumes at the facility.

More recently, the local news media have reported developments aimed at improving Jackson’s financial situation. Jackson’s chief executive officer announced in November 2010 she would not renew her contract, and a replacement was hired—a banker with limited health care experience. Also, the County Commission replaced the 17-member Public Health Trust with a seven-member Financial Recovery Board to address Jackson’s immediate financial problems and appointed a 20-member Hospital Governance Task Force to establish a long-term governance structure. In May 2011, the task force recommended converting Jackson Health System to a nonprofit entity that would be managed by a nine-member independent board. However, after a series of public forums, a recent media report indicated that Jackson’s unionized workforce and the County Commission do not support privatizing the system.

Jackson reportedly has made some headway in cutting costs by eliminating job positions—many vacant—and boosting revenues through improved debt collection. Additional plans in the works include renegotiating with employee unions, expanding outpatient services in more-affluent areas, and lowering rates charged to HMOs in an effort to attract more privately insured patients. However, Jackson is grappling with significant financial deficits in its JMH Health Plan, which serves the commercial and Medicaid markets, and has lost some state funding to help cover the costs of treating uninsured patients because of changes in the way the state allocates the low-income pool. Jackson’s proposed fiscal year 2012 budget includes significant cuts in labor and payment to UHealth for physician services.

In contrast to Jackson’s precarious situation, Miami’s other safety net providers are relatively stable. Homestead Hospital, part of the Baptist network, continues to serve a large safety net role in the far southern part of the county, an area with many migrant workers. Being part of the Baptist system provides Homestead financial stability; Homestead also benefited from the recent reallocation of the state low-income pool funds. Miami has eight free clinics primarily serving people without insurance, as well as six federally qualified health center (FQHC) organizations—the largest of which are Community Health of South Florida (CHI) and Jessie Trice Community Health Centers, each with seven clinic sites. While health center capacity overall has not changed significantly, FQHCs received federal stimulus funding to help serve more patients and make capital improvements. Still, CHI had to reduce urgent care hours in the wake of budget cuts.

Surprisingly, the growing number of uninsured people in Miami has not had a major impact on patient volumes at FQHCs and other outpatient providers. Some, including CHI, experienced a small increase in volume, while others, in addition to Jackson, experienced a decline. It is unclear why demand for care at these facilities did not increase during the recession. Some respondents suggested that uninsured patients may be unwilling or unable to pay the sliding-scale fees at FQHCs, instead favoring hospital emergency departments or free clinics that have smaller or no fees. Jackson and Homestead have experienced increases in ED volumes of 5-10 percent in each of the past three years.

Back to Top

Fledgling Efforts to Coordinate Safety Net

Although Jackson Health System is a public entity and the largest safety net provider, market observers reported Jackson does not provide strong leadership for the Miami safety net, in part because of preoccupation with financial challenges. Instead, the Miami safety net is fragmented compared to many other communities, and the relationships among providers are often more competitive than cooperative. For example, Jackson proposed converting its primary care clinics to FQHCs to obtain enhanced Medicaid reimbursement, but other FQHCs objected that this would increase competition for Medicaid patients in overlapping service areas.

There is widespread recognition in the community that greater integration and coordination among safety net providers could improve access to care and make more efficient use of increasingly strained resources. The Miami-Dade Health Action Network, which was established in 2008 with county health department funding, is one recent effort to improve coordination among safety net providers. The network is a partnership of free clinics, hospitals, FQHCs and nonprofit community organizations with the broad goal of improving delivery of services to the uninsured through efficient sharing of health information, the implementation of a countywide referral system, and the provision of coordinated care through a medical home. Yet, the Action Network’s impact has been limited to date, in part because it appears to lack the leadership necessary to get providers and stakeholders to work together in an effective way.

More narrowly focused initiatives appear to have a more significant impact. The FQHCs in Miami belong to the Health Choice Network (HCN), a coalition of FQHC providers in nine states that share common business, technology and administrative services. Their participation has allowed the FQHCs in Miami-Dade to share the same information technology and billing systems, which has contributed to a much improved financial situation at Jessie Trice CHC. Also, HCN is coordinating the South Florida Regional Extension Center to achieve federal designation of meaningful use and support for health information technology.

Back to Top

Medicaid Feared Unsustainable

Florida’s Medicaid enrollment increased dramatically during the economic downturn—by approximately one-third since 2007, reaching more than 2.9 million people by July 2011 out of a total state population of about 19 million. Healthy Kids—the state’s Children’s Health Insurance Program for those aged 5 to 18—has grown less dramatically than Medicaid during the same period, perhaps because Healthy Kids requires parents to pay premiums and because the recession has pushed family incomes low enough for more children to qualify for Medicaid.

With more than 550,000 Medicaid enrollees and about 44,000 Healthy Kids children living in Miami-Dade County—representing about 20 percent of statewide enrollment in each program—any substantial changes in Florida’s Medicaid program would have a major impact on Miami residents and health care providers.

Because of budget shortfalls, the state in 2010 reduced Medicaid payment rates to many hospitals by 7 percent for inpatient and outpatient services. The effects of these cuts on Jackson were mitigated as counties were able to “buy back” these dollars through the state’s Medicaid waiver, by putting up county funds to receive federal matching dollars. However, the state cut hospital rates by another 12 percent for 2011-12.

Medicaid costs in Miami-Dade County continue to be of great concern to the state, given the size of the Medicaid population and continued enrollment growth. A state auditor’s report estimated that Medicaid expenditures could reach one-third of the state budget by 2014, up from about one-quarter today. The report also raised questions about hundreds of millions of dollars in unauthorized Medicaid payments to providers and inadequate documentation of Medicaid eligibility for many enrollees, creating more pressure for improvement.

The governor is trying to expand Medicaid managed care significantly, including statewide expansion of a 2006 pilot program that made managed care mandatory for most Medicaid enrollees in five counties. Currently, about a third of Medicaid enrollees in Miami-Dade County are in managed care, with the remaining two-thirds split between fee for service and MediPass, a state-administered primary care case management program. In August 2011, state officials applied for federal-waiver amendments to extend the pilot and move the aged, blind and disabled Medicaid population into managed care. Safety net providers and other advocates for low-income people oppose expansion of Medicaid managed care, believing that the program is not feasible for the larger, sicker and more ethnically diverse Medicaid population in Miami. Safety net providers also are concerned that they would lose a substantial amount of Medicaid funding.

To help shield themselves from potential financial losses, Miami Medicaid providers are exploring options for participating in the expansion of Medicaid managed care through their Provider Service Networks (PSNs). PSNs function similarly to HMOs but with majority ownership by participating providers. Since 2000, the Miami-Dade Public Health Trust and providers in Broward County have operated the South Florida Community Care Network PSN, with more than 8,000 Medicaid enrollees in Dade County. In 2008, the FQHCs’ Health Choice Network began operating a PSN called Prestige Health Choice. Health plans are insisting on a level playing field, arguing that PSNs should be required to assume financial risk and to conform to the same regulations as health plans if they compete for Medicaid managed care contracts.

Back to Top

Anticipating Health Reform

The direction the Miami health system takes over the next few years likely will depend on both the extent of an economic recovery and the impact of national health reform implementation. Given the recession’s particularly severe impact on Miami, the health care system likely would benefit substantially from a recovery that increased employment and the number of people with access to employer-based insurance. The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) could have a favorable financial impact on Miami’s health care providers, given the large number of uninsured people in the community who likely would become insured.

Also, insurance exchanges mandated by health reform could play an important role in organizing the growing individual insurance market in Miami. However, health plans are concerned that new regulations regarding medical-loss ratios could inhibit development of innovative, more-limited plan options in the individual and small-group markets in Miami, as well as disrupt the existing markets.

But how health care reform in Florida plays out appears highly uncertain, with state officials saying the law will not be enforced in the state. Gov. Rick Scott and the Republican-controlled Legislature oppose the law and declined to pursue or accept new federal money, for example, to set up a state insurance exchange. Florida also is a plaintiff in suits challenging the law. And, given that undocumented immigrants will not gain coverage under the law, hospital executives expressed concerns about significant numbers of uninsured patients remaining while facing declines in special funding to help cover the costs of their care—for example, Medicaid disproportionate share hospital funding will be reduced.

Back to Top

Issues to Track

- Will geographic competition among hospitals for well-insured patients continue at the same level of intensity? Will it undermine hospital leverage with health plans?

- Will the changing characteristics of the Miami market—specialist physician consolidation, declining health plan negotiating leverage and aggressive hospital expansion strategies—raise health care costs?

- Will narrow-network insurance products become more common in Miami and more acceptable to consumers in the face of rising health care costs?

- Will subsidized insurance and insurance exchanges under health reform lead to a better organized, more efficient individual insurance market? How will the limited-benefit products being developed and marketed by plans need to be modified to be offered in insurance exchanges?

- Will county leaders find a way to improve the oversight and management of Jackson Health System to improve its financial position and potentially allow it to take on more of a leadership role in the safety net?

- What impact will health reform have on the large proportion of people uninsured in Miami, particularly given concerns about the state’s ability to finance the Medicaid expansion and provider concern about changes in Medicaid managed care, as well as the large number of immigrants in this community who will be ineligible for Medicaid or subsidized coverage?

Back to Top

Background Data

| Miami Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Miami Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Population, 20091 | 2,500,625 | |

| Population Growth, 5-Year, 2004-20092 | 5.0% | 5.5% |

| Age3 | ||

| Under 18 | 22.3% | 24.8% |

| 18-64 | 62.3% | 63.3% |

| 65+ | 15.4%* | 11.9% |

| Education3 | ||

| High School or Higher | 77.3%# | 85.4% |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 27.8% | 31.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity4 | ||

| White | 17.8%# | 59.9% |

| Black | 17.6% | 13.3% |

| Latino | 62.4%* | 18.6% |

| Asian | 1.4% | 5.7% |

| Other Races or Multiple Races | 0.8%# | 4.2% |

| Other3 | ||

| Limited/No English | 34.8%# | 10.8% |

| # Indicates a 12-site low. * Indicates a 12-site high.Sources: 1 U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2009 2 U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2004 and 2009 3 U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2008 4 U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2008, weighted by U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2008 |

||

| Economic Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Miami Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Individual Income less than 200% of Federal Poverty Level1 | 38.4%* | 26.3% |

| Household Income more than $50,0001 | 45.4% | 56.1% |

| Recipients of Income Assistance and/or Food Stamps1 | 14.7%* | 7.7% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance1 | 28.1%* | 14.9% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20082 | 6.5% | 5.7% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20093 | 10.7% | 9.2% |

| Unemployment Rate, June 20104 | 13.1% | 9.4% |

| * Indicates a 12-site high.

Sources: |

||

| Health Status1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Miami Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Chronic Conditions | ||

| Asthma | 7.7%# | 13.4% |

| Diabetes | 8.4% | 8.2% |

| Angina or Coronary Heart Disease |

5.5% | 4.1% |

| Other | ||

| Overweight or Obese | 58.7% | 60.2% |

| Adult Smoker | 7.9%# | 18.3% |

| Self-Reported Health Status Fair or Poor |

14.4% | 14.1% |

| # Indicates a 12-site low. Sources: 1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2008 |

||

| Health System Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Miami Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Hospitals1 | ||

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population |

3.4 | 2.5 |

| Average Length of Hospital Stay (Days) |

5.5 | 5.3 |

| Health Professional Supply | ||

| Physicians per 100,000 Population2 |

259 | 233 |

| Primary Care Physicians per 100,000 Poplulation2 |

92 | 83 |

| Specialist Physicians per 100,000 Population2 |

167 | 150 |

| Dentists per 100,000 Population2 |

55 | 62 |

| Average monthly per-capita reimbursement for beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare3 |

$1,110* | $713 |

| * Indicates a 12-site high.

Sources: |

||

Funding Acknowledgement

The 2010 Community Tracking Study and resulting Community Reports were funded jointly by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institute for Health Care Reform. Since 1996, HSC researchers have visited the 12 communities approximately every two to three years to conduct in-depth interviews with leaders of the local health system.