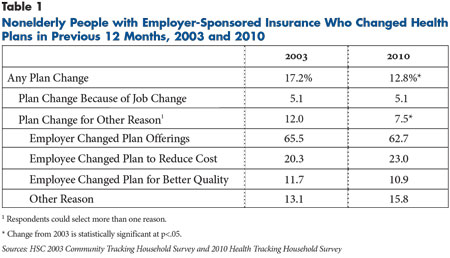

About one in eight (12.8%) nonelderly Americans with employer coverage switched health plans in 2010—down from one in six (17.2%) in 2003, according to a new national study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). As was true in 2003, about 5 percent of people with employer coverage switched plans in 2010 because of a job change. However, the proportion of people younger than 65 with employer coverage changing plans for other reasons fell from 12 percent in 2003 to 7.5 percent in 2010—in both years the main reason for switching plans was a change in employer benefit offerings. Less than 2.5 percent of workers in 2010—about the same proportion as in 2003—initiated a change in plans to reduce their health insurance costs or to get a better quality plan, such as better benefits or a more desirable provider network. These findings suggest that consumer choice plays a relatively small role in health plan switching, with most changes resulting from job changes or changes in employers’ plan offerings. National health reform may create opportunities to increase plan choice among people with employer-sponsored coverage, particularly those in small firms, resulting in more frequent switching of health plans. However, a potential downside of more switching is less stable patient-provider relationships, such as in a medical home.

- Job Changes, Employer Offerings Drive Most Health Plan Switches

- Plan Switching Declines Between 2003 and 2010

- Healthier More Likely to Switch Plans

- Consumer Choice and Plan Switching

- Plan Choice vs. Provider Stability

- Implications

- Notes

- Data Source

Job Changes, Employer Offerings Drive Most Health Plan Switches

The rate at which people change health plans is one indicator of the degree of choice and competition in health insurance markets, which many believe are essential to reduce health care costs and improve quality.

For people with employer-sponsored health insurance, opportunities to change health plans are largely constrained by whatever choices employers offer. About half of workers with employer coverage are offered a single plan by their employer, while only about 15 percent of workers has a choice of three or more plans.1 Even when choices are available, decisions to change plans may be constrained by a lack of comparative information to make informed decisions on costs, covered benefits and quality of care.2

Among people younger than 65 with employer coverage in 2010—and who were continuously enrolled in private insurance during the preceding 12 months3—12.8 percent changed plans during the previous year, according to findings from HSC’s nationally representative 2010 Health Tracking Household Survey (see Data Source and Table 1). Forty percent of the plan changers—or 5.1 percent of all with employer coverage—switched plans because of an employment change. While job changes may be motivated in part to obtain better benefits, most people change jobs because of other factors, such as obtaining higher overall compensation, a shorter commute, better working conditions, professional advancement or termination by the previous employer.

Thus, only 7.5 percent of those with employer coverage changed plans because of an explicit decision by employers or employees. Of the 7.5 percent, most switched plans because of a change in their employers’ benefit offerings (62.7%). The other third of plan changes were worker initiated—usually to obtain a less expensive plan or better quality plan. Among all nonelderly people with employer coverage, 2.3 percent changed plans in 2010 in search of better quality or lower costs.

Plan Switching Declines Between 2003 and 2010

Plan switching among nonelderly people with employer coverage decreased from 17.2 percent in 2003 to 12.8 percent in 2010. This change was driven entirely by a decrease in plan switches for reasons other than a job change—from 12.0 percent in 2003 to 7.5 percent in 2010. Plan switching related to job changes held steady during this period, at about 5 percent.

The decrease in plan switching parallels a decrease in employer-sponsored coverage among workers in small and medium-sized businesses who change plans more frequently compared to workers in larger firms. The rate of employer coverage among workers in firms with fewer than 500 workers decreased from 63 percent in 2003 to 54 percent in 2010, while employer coverage among workers in larger firms—500 workers or more—held steady at about 83 percent (findings not shown).

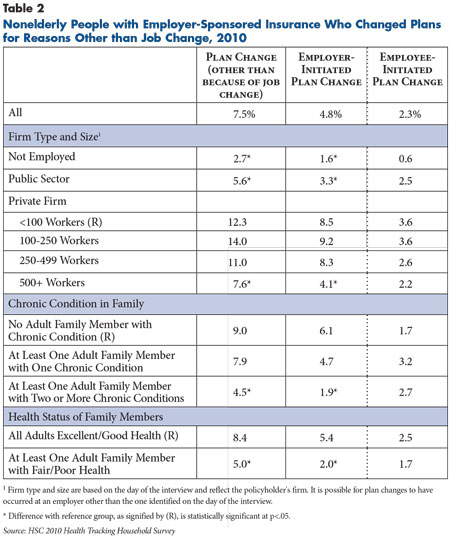

Plan switching is more frequent among workers with coverage from small firms compared to workers in larger firms. Among people with coverage from a firm with fewer than 100 workers, 12.3 percent changed health plans for reasons other than a job change, compared to 7.6 percent in firms with 500 or more workers, and 5.6 percent among public-sector workers (see Table 2).

Most of this difference reflects more frequent changes in plan offerings by small businesses, most likely to reduce their insurance costs. Small firms typically have higher insurance costs than larger firms for a variety of reasons, including higher administrative costs, a smaller risk pool and greater vulnerability to premium spikes that occur when workers have serious health problems. Interestingly, plan switching is more frequent in small firms compared to larger firms despite the fact that larger firms and public employers typically offer workers a greater choice of health plans.4

Healthier More Likely to Switch Plans

People with health problems—or who have family members with health problems—are less likely to change plans compared to healthier people. Among people in families in 2010 without an adult with a chronic condition, 9 percent changed plans in the past year, which is double the rate when at least one adult family member has two or more chronic conditions. Similarly, among people in families where all adults are in excellent or good health, 8.4 percent changed health plans, compared to 5 percent of people in families where at least one adult was in fair or poor health.

The higher rate of plan switching among healthier people results primarily from a higher rate of employer-initiated plan changes rather than employee-initiated changes. Many people with health problems—or who have family members with health problems—are not employed. For example, they may be retired with coverage from a former employer—a situation where plan switching is much less frequent. Also, people who are sicker or have sick family members may self-select into larger firms where health benefits tend to be more extensive and stable. Although one might expect people with health problems to initiate plan changes less frequently than healthy people—so as not to risk any change in their provider network—there were no significant differences in employee-initiated changes by prevalence of chronic conditions.

Consumer Choice and Plan Switching

The low rate of employee-initiated plan changes (2.3%) is perhaps not surprising given that there is often little or no choice of plans offered by employers, along with a high time investment to switch plans because of a lack of easily accessible information on how plans compare in terms of benefits, quality of services and out-of-pocket costs. However, it is unclear how much plan switching would occur if people with employer coverage had more plan options and easily accessible and understandable information to help them choose a plan.

Many observers consider the Federal Employee Health Benefits Program (FEHBP) to be a model for a competitive market for group health insurance in that it provides workers with a wide variety of plan choices at reasonable cost, as well as a number of tools and publications specifically designed to help workers compare their plan choices in terms of costs, benefits and satisfaction. One study found that about 12 percent of FEHBP enrollees switched plans in a single year (2000-01), which is much higher than the rate of employee-initiated plan changes shown in this study, including the rate for public-sector workers.5

One possible reason for this much higher rate of plan switching within FEHBP is that not only are there more plan offerings in general, but there tends to be multiple offerings within plan types—for example, multiple preferred provider organizations (PPOs) and health maintenance organizations (HMOs). In fact, three-fourths of FEHBP plan switchers stayed with the same plan type—for example, those with PPOs switched to a different PPO plan rather than switching to an HMO plan. Switching from one plan type to another was much less frequent in the FEHBP. By contrast, even when workers in the private sector have a choice of plans, they are less likely to be offered multiple options within a plan type compared to federal workers. Instead, workers often are offered different plan types from a single carrier. Therefore, the much lower rate of employee-initiated plan changes shown in this study may reflect in part much greater reluctance among workers to change plan type even when they have a choice because it could involve a change in their choice of providers or the way their care is delivered.

Plan Choice vs. Provider Payment

Many private- and public-sector initiatives are underway with a goal of reforming medical care delivery to improve quality and reduce costs. Many of these reforms, such as accountable care organizations and patient-centered medical home initiatives, emphasize patients having a stable source of primary care and improved coordination of specialty care. Increasing health insurance choice—and the rate of plan switching—may be contrary to the objectives of delivery system reform if a change in plans also results in a change of primary care provider because of provider network differences among plans. Moreover, purchaser interest in limited-network products may increase the potential for plan switching to disrupt existing patient-provider relationships.

Also, frequent churning in the private insurance market provides a disincentive for health plans and purchasers to invest in preventive care and care management of chronic conditions with the expectation that these services will have longer term payoffs. If plans and purchasers do not believe that sufficient numbers of enrollees will remain in the plan long enough to realize these savings, they may be less likely to initiate such programs. This may be less of a factor for self-insured employers that can maintain the same programs even when they change carriers.

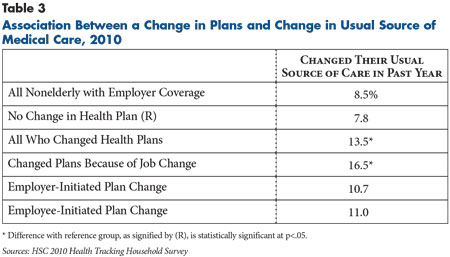

Findings from the 2010 Health Tracking Household Survey show that people who changed plans in the past year also were more likely to change their usual source of care—the place they usually go for help or advice for a medical problem. Among people who changed health plans, 13.5 percent also changed their usual source of care, compared to 7.8 percent of people who did not change plans (see Table 3). However, changes in the usual source of care were more frequent among people who changed plans because of a job change (16.5%), while employer and employee-initiated changes in health plans were less likely to be associated with a change in usual source of care. Job changes will necessarily require a change in the usual source of care if it involves a change in residence. That employer and employee-initiated plan changes are less likely to lead to a change in people’s usual source of care may reflect the availability today of broad provider networks that often differ little across health plans.

Of course, a desire for a different primary care provider may precipitate a change in health plans in some cases. That is, people may change plans to gain access to a choice of additional providers. Nevertheless, it will be important to monitor whether the goals of increasing competition and choice in the health care marketplace prove to complement or conflict with the goals of delivery reform that place greater emphasis on stable patient-provider relationships.

Implications

The low rate of employer and employee-initiated plan switching indicates that plan choice is not an important feature of the private, employer-based system that most Americans rely on for health insurance. Moreover, the prevalence of plans with broad provider networks over the past decade means workers with a choice of plans likely have been able to switch plans to lower their out-of-pocket costs without being concerned about changing providers. With the emergence of limited-network and tiered-network products, plan changes in the future may either require a change in providers or higher out-of-pocket costs to continue seeing existing providers.

Although the national health reform law does not directly affect choice of plans through employers, some provisions may increase plan choice for workers and their families. Starting in 2014, states will be required to either create insurance exchanges for small businesses with up to 50 workers—and up to 100 workers after two years—or to allow small businesses to participate in the state exchanges for nongroup health plans. In states that do not create exchanges, the federal government will operate the exchanges. Beginning in 2017, states will have the option of allowing businesses with more than 100 workers to participate in the exchanges. Not only is there likely to be more choice of plans in the exchanges compared to what exists in the small-group insurance market today, but changing plans may be easier because exchanges are required to assist people with enrollment and provide comparative information on plan benefits, costs and quality.

In addition, the availability of subsidized nongroup coverage through exchanges could indirectly increase plan switching by decreasing so-called job lock, or the reluctance of people to change jobs or become self-employed for fear of losing employer coverage. Although estimating the extent of job lock is difficult, estimates from the 2010 Health Tracking Household Survey indicate that 6.5 percent of working families with employer coverage reported passing up a job offer in the past year to avoid losing current health benefits. State-based insurance exchanges could encourage more plan switching from the group to nongroup markets by making it easier for people to change to a job that does not offer health benefits or to become self-employed.

Notes

1. Kaiser Family Foundation, Menlo Park, Calif., and Health Research & Educational Trust, Chicago, Ill., Employer Health Benefits: 2012 Annual Survey (September 2012).

2. Cebul, Randall D., et al., “Unhealthy Insurance Markets: Search Frictions and Cost and Quality of Health Insurance,” American Economic Review, Vol. 101, No. 5 (August 2011).

3. The sample for this study includes persons younger than 65 who were covered by employer-sponsored insurance on the day of the interview and were continuously covered by private insurance during the preceding 12 months. Respondents who reported switching plans were asked only if the previous coverage was private. The vast majority likely switched from one employer plan to another, but some may have switched from nongroup to employer coverage because they got a job with health benefits.

4. Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust (2012).

5. Aderly, Adam, Curtis Florence and Kenneth E. Thorpe, “Health Plan Switching Among Members of the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program,” Inquiry, Vol. 42, No. 3 (Fall 2005).

Data Source

This Research Brief presents findings from the HSC 2010 Health Tracking Household Survey and the HSC 2003 Community Tracking Study Household Survey, both of which were funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Both are telephone surveys that included nationally representative samples of the civilian noninstitutionalized population. The 2010 survey included a cell phone sample because of declining percentages of households with landline phones. Overall sample sizes included 46,600 persons in the 2003 survey and 16,700 in the 2010 survey. Response rates for the surveys were 57 percent in 2003 and 46 and 29 percent, respectively, for the landline and cell phone samples in the 2010 survey. Population weights adjust for probability of selection and differences in nonresponse based on age, sex, race/ethnicity and education. The weights also adjust for the increased probability of selection in cases of households using both landline and cell phones. Although both surveys are nationally representative, the 2003 sample was clustered in 60 representative communities, while the 2010 survey was based on a random sample of the nation. Estimates of standard errors account for the complex sample design of the surveys. Questionnaire design and survey administration was similar across the two surveys.

The sample for this study includes persons younger than 65 who were covered by employer-sponsored insurance on the day of the interview and were continuously covered by private insurance during the preceding 12 months. This includes about 25,900 persons for the 2003 survey and 7,600 persons for the 2010 survey. To determine whether a sample person had a change in health plans, the survey asks whether individuals enrolled in their current health plan in the past 12 months. Persons who enrolled in their current plan in the past 12 months but were enrolled in another private insurance plan prior to their current plan were considered to have changed private insurance plans. For people who changed plans, the survey also asked the reasons why they changed plans. Precoded responses included a change in employment; employer offerings changed; current plan is less expensive; current plan has better services, preferred doctors, better quality; or some other unspecified reason.