In February 2010, a team of researchers from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) visited the Detroit metropolitan area on behalf of the National Institute for Health Care Reform to study how health care is organized, financed and delivered in that community. Researchers interviewed more than 55 health care leaders, including representatives of major hospital systems, physician groups, insurers, employers, benefits consultants, community health centers, state and local health agencies, and others. The study area encompasses Lapeer, Livingston, Macomb, Oakland, St. Clair and Wayne counties.

The challenges facing the Detroit metropolitan area’s health care system are intertwined with the challenges facing the community as a whole, including a declining and aging population; major suburban/urban differences in income, employment, health insurance coverage, and health status; and a shrinking industrial base. These realities affect all of the various components of the area’s health care system, shaping the ongoing changes in the financing and delivery of medical care. At the same time, as the Detroit area develops an overall strategy for economic renewal going forward, some envision the health care system as playing a major redevelopment role, to the point that “Medicine could possibly replace motors as the engine of Detroit,” according to a May 2010 National Public Radio broadcast. While this view may be overly optimistic, there is evidence of considerable vitality in Detroit’s traditionally strong health care system.

- Increasing cooperation between physicians and hospitals, at the same time competition among hospitals intensifies amid major investments in health care infrastructure.

- A growing focus by health plans, providers and employers on quality improvement and increased accountability for patient care outcomes.

- Community willingness to work collaboratively to address difficult issues relating to care for the poor and uninsured.

- Market Background

- Hospital Market Responds to Financial Challenges

- Hospitals and Physicians Redefine Relationships

- Quality Improvement Efforts Grow

- Health Plans and Employers Support Wellness Initiatives

- Concerns About Safety Net Capabilities

- Issues to Track

- Detroit Background Data

Market Background

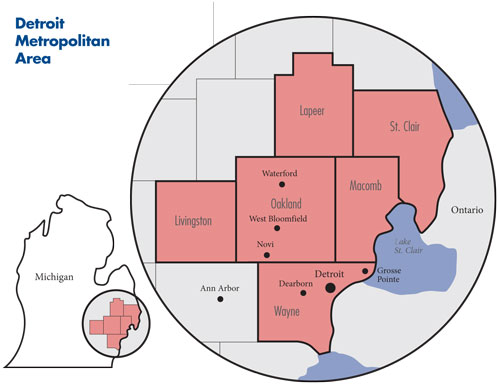

The population of the greater Detroit metro area (see map below) is now approximately 4.2 million, after declining about 2 percent in the last five years. About 900,000 people currently live in the city of Detroit—half of the city’s peak population of 1.8 million in the 1950s. There are stark differences in the demographics—income, health insurance coverage, health status, employment and race—of the city and surrounding suburbs.

The 2008 median household income in the city of Detroit was dramatically less ($29,423) than the median for the metro area as a whole ($54,359). Similarly, the uninsurance rate in 2008 for the city was significantly higher (18.9%) than the rate for the metro area (12.0%). In February 2010, the city of Detroit unemployment rate (24.8%) was much higher than the metro area rate (15.3%). During 2006-08, on average, about 85 percent of Detroit residents were African American, compared with about 10 percent outside of the city limits. In the metro area as a whole, 72 percent of residents were white and 23 percent were African American.

Further, the Detroit metropolitan area’s economy has lagged that of other metropolitan areas, on average. Between 2005 and 2008, household income in the Detroit metro area rose by 7 percent, considerably less than for the nation (12.8%). In 2008, the proportion of people in the metro area lacking health insurance was approximately 15 percent, close to the national average of 15.1 percent, but the Detroit-area uninsurance rate increased to 18 percent in 2009. Likewise, in 2009, a much larger proportion of Detroit city residents reported their health status as fair or poor (24.3%) compared with residents outside the city limits (13.4%).

The current Detroit metropolitan unemployment rate is among the highest for U.S. metropolitan areas. Of particular note, national unemployment rates dropped from 2003 through October 2006, following recovery from the 2001 recession, while the Detroit area’s unemployment rate continued to rise. This reflects, in part, substantial shrinkage of the area’s manufacturing sector—between 2002 and 2007, manufacturing jobs decreased 24 percent, representing a loss of more than 70,000 jobs.

Most of this job loss was directly or indirectly related to automobile manufacturing, as automakers—Chrysler, Ford Motor Company and General Motors—responded to financial difficulties by cutting costs through workforce reductions. The automobile manufacturers identified high health care costs associated with retired American workers, as well as current employees, as one of the major factors contributing to their financial problems. For example, General Motors reportedly spent $5.4 billion on health care in 2005, with more than two-thirds consisting of retiree expenses.

In 2005 negotiations, the International Union, UAW; Ford; and General Motors agreed to create a Voluntary Employees Benefit Association (VEBA) at each company to take responsibility for a portion of retiree health liabilities going forward in return for a schedule of payments. In 2007, an agreement was reached to transfer all retiree health liabilities at all three manufacturers to the VEBAs. The bankruptcies at Chrysler and General Motors, which led to payment for some of the obligations in company stock, increased uncertainty about the amount of resources that the VEBAs will have to pay for retiree health care. The UAW Retiree Medical Benefits Trust, which manages each of the VEBAs, began operations in January 2010, at which time it became the largest single purchaser of health benefits in the metropolitan area and a potential force in shaping changes in the Detroit health care system.

Hospital Market Responds to Financial Challenges

Following earlier hospital consolidation, there are several major nonprofit hospital systems in metro Detroit, with each capturing from 11 percent to 18 percent of inpatient admissions across the market. In contrast, the health insurance market is heavily concentrated, with the dominant nonprofit Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan competing with two smaller, nonprofit provider-owned health plans—Health Alliance Plan (HAP) and Priority Health—for enrollment.

The major hospital systems include the Henry Ford Health System, which operates five acute care hospitals, owns a medical group and operates HAP; Detroit Medical Center (DMC), which operates nine hospitals, including the Children’s Hospital of Michigan and five other acute care hospitals; St. John Providence Health System, with seven acute care hospitals; and Beaumont Hospitals, with four acute care hospitals, including Beaumont Children’s Hospital.

Significant, but smaller, hospital systems include Dearborn-based Oakwood Healthcare System, with four acute care hospitals in suburban Wayne County, and Trinity Health, a statewide system with four acute care hospitals in the Detroit suburbs. The University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor is at the edge of the Detroit metropolitan area but is regarded by other systems as a competitor, especially for financially desirable insured patients in the western Detroit suburbs. The university system also offers some specialty services not available at other area hospitals.

Hospital systems have expanded their presence in the Detroit suburbs over the past decade, a strategy intended to improve access to privately insured patients. At the same time, hospital systems reduced their inner-city capacity in response to the declining population and falling margins. At least five hospitals in the city of Detroit, totaling about 1,500 inpatient beds, have closed since 1998. The Henry Ford Health System recently opened a new suburban hospital in Oakland County—Henry Ford West Bloomfield Hospital—following the 2007 outright purchase of a jointly owned, small hospital (Cottage Hospital) in Grosse Pointe from Bon Secours Health System, a national Catholic system that exited the Michigan market. As a result, Henry Ford has become the largest hospital system in the Detroit area, measured by number of admissions.

In 2007, in response to the planned opening of Henry Ford West Bloomfield Hospital and seeking a larger presence in the eastern Wayne County suburbs, Beaumont purchased Bon Secours Hospital in Grosse Pointe. St. John Providence Hospital System, part of the national Ascension Health system, is predominantly in the suburbs, with one hospital on the east side of Detroit. In 2007, St. John closed Detroit Riverview Hospital near downtown Detroit, converting it to an urgent care center, and opened Providence Hospital in Novi in suburban Oakland County. Some respondents noted that these suburban hospitals are facing additional competition from Flint-based McLaren Health Care Corp. expanding into the outskirts of the Detroit metro area.

The state health department turned down certificate-of-need requests from both Henry Ford and St. John to build the new suburban hospitals. Despite significant employer concern that the facilities were unneeded and would increase costs, both hospital systems appealed successfully to the state Legislature to gain exemptions from certificate-of-need requirements designed to control the growth of health care facilities and services.

The hospital systems’ competitive strategies are a direct reflection of the economic situation in Detroit. Growing rates of unemployment and uninsurance in the city of Detroit have slowed growth in patient volume and service utilization for hospitals there, while increasing the amount of uncompensated care provided by hospitals. As one respondent noted, “We have a massively growing underinsured or uninsured population that has absolutely ballooned over the last few years.” Most hospitals, including those in the suburbs, have experienced a rise in both charity care and bad debt in the past several years. This has intensified competition for profitable privately insured patients with comprehensive benefits who can help offset losses on uninsured and Medicaid patients, as well as bad debt and declining demand from insured patients whose coverage includes more patient cost sharing.

There are indications that the financial situation for hospitals has improved recently. For example, Detroit Medical Center, St. John and Beaumont reported small positive operating margins in 2008. In recent years, hospitals have negotiated increased payment rates from their largest commercial payer—Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan—while instituting cost-cutting strategies that, in the case of Beaumont and St. John, have included significant workforce reductions. For Henry Ford and St. John, revenue from new facilities also has contributed to their improved financial situations.

In a development that surprised many at other hospital systems, Detroit Medical Center announced its intent on March 19, 2010, to be acquired by Vanguard Health Systems, a national for-profit hospital chain. Detroit Medical Center’s hospitals are in the city of Detroit, with the exception of one hospital in suburban Oakland County. The improved financial performance of DMC hospitals over the last several years—attributed to better management—reportedly made DMC a more attractive acquisition for Vanguard. The purchase could provide Detroit Medical Center with better access to capital for renovation and possibly expansion of its physical plant.

Vanguard has promised to invest $850 million in capital improvements over the next five years, including $800 million in the city of Detroit. Vanguard also has committed to continuing the same charity care policies now followed at Detroit Medical Center and not to close any hospitals for the next 10 years. However, some community stakeholders have voiced concerns that Vanguard, which is already heavily leveraged and is issuing more debt to acquire DMC, will renege on these promises to the community.

Two weeks after the proposed DMC purchase by Vanguard was announced, Henry Ford announced a plan to invest $500 million in its flagship downtown Detroit hospital, including housing, retail and other commercial activities near the hospital. The investment plans outlined by Vanguard and Henry Ford have been received enthusiastically by city leaders, who see them as an important part of a hoped-for economic turnaround for the city.

Overlooked in the enthusiasm that health care can help jumpstart the metro Detroit area’s economy is the possibility that significant expansion in health care infrastructure may lead to increasesd use of high-tech services or additional costs from excess capacity, driving health spending higher. In this case, the end result might be higher private health insurance premiums, which could have a negative impact on employers and employees.

Hospitals and Physicians Redefine Relationships

The physician market in Detroit is much more fragmented than the hospital market, with many one-, two- and three-physician practices. There are, however, a small number of larger physician organizations. Large medical groups in the Detroit area include the Henry Ford Medical Group (more than 1,000 physicians), the University of Michigan Faculty Group Practice (about 1,600 physicians) and the Wayne State University Physicians Group (550 physicians). In addition, there are several large physician organizations that could be characterized as independent practice associations (IPAs): United Outstanding Physicians, with more than 1,000 employed and affiliated physicians, and United Physicians, with more than 1,600 physicians; or as a physician hospital organization (PHO): St. John HealthPartners with 2,200 physicians. The IPAs and PHO negotiate some payment rates with health plans and health care systems for affiliated physicians, but participating physicians retain ownership of their individual practices.

Physicians face many of the same financial challenges as Detroit hospitals, especially a declining number of insured patients. Moreover, physicians have received lower reimbursement rate increases, compared with hospitals, from Blue Cross Blue Shield. As a result, a growing number of both primary care and specialist physicians are seeking the financial security and practice support associated with hospital employment or other close hospital affiliations.

As one hospital respondent explained, “The primary benefit of partnering with the hospital is the access to capital and other operational support around some of our capital investment strategies such as clinical IT [information technology].” Hospitals welcome closer physician alignment, seeing it as a key to their success, especially if the recently enacted health reform law spurs the creation of so-called accountable care organizations (ACOs) that integrate physicians and hospitals for payment and quality improvement purposes. Purchasers, however, have concerns that the creation of large ACOs may concentrate market power, giving providers greater leverage in rate negotiations with health plans.

Hospitals are concerned that Detroit’s economic situation will discourage new physicians, especially primary care physicians, from establishing practices in the community. As a consequence, all health care systems have either purchased medical groups or increased their number of employed physicians. St. John and Beaumont now employ roughly 25 percent of their medical staffs. Henry Ford through ownership of the Henry Ford Medical Group has traditionally embraced physician employment and has increased the number of employed physicians.

All of the major hospital systems are modifying their electronic medical record (EMR) systems to improve information access for affiliated physicians. Hospitals also are providing financial and technical support to select affiliated physicians, particularly primary care physicians, to assist them in acquiring and implementing EMRs. And, hospitals are offering staff and administrative support to primary care practices working toward designation as medical homes. Beaumont is partnering with a state university to open the Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine in 2011, believing that the health system’s affiliation with a medical school will ease physician recruitment and establish Beaumont as a major academic medical center.

While physicians and hospitals have pursued a variety of paths toward closer affiliation, they have not always been successful. Often, disagreements revolve around the desire by physicians to own freestanding facilities, such as ambulatory surgery centers, that offer services in direct competition to hospitals where they serve on the medical staff. This can sometimes contribute to contentious public disputes between hospitals and medical groups. For instance, last year, Beaumont severed its relationship with United Physicians for this and other reasons, creating a competing organization called Beaumont Physicians. This new organization includes Beaumont-employed physicians and is recruiting independent physician practices to join.

Quality Improvement Efforts Grow

Medical care providers in metropolitan Detroit are actively engaged in a wide range of quality improvement activities, typically in collaboration with health insurers and community organizations and with the encouragement of large employers. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM), with a 70 percent share of the commercial market in the state, has played an instrumental role in many of these activities, although some employers would like BCBSM to be more aggressive in this area.

BCBSM negotiates a standard hospital contract periodically with the Michigan Health & Hospital Association, setting parameters for negotiations with individual hospitals. Hospitals receive “prepayments” from BCBSM for services, with reconciliation occurring annually. Recent annual reimbursement increases for hospitals have been in the 2-percent to 3-percent range. Physicians typically receive standard fee-for-service contracts with fee increases, normally in the range of 1 percent to 2 percent, tied to general inflation. Over the last several years, BCBSM has increased the proportion of provider reimbursement that is linked to specific performance measures. Currently, in hospital contracts, 4 percent of payment is based on performance on quality measures and 1 percent on efficiency measures, with physician payments structured in a similar manner.

A portion of the annual hospital incentive payments—$11 million—is for hospital participation in Collaborative Quality Initiatives, which are hospital-run initiatives where providers share data with each other to determine best practices for complex and rapidly changing services with little evidence base. Blue Cross Blue Shield intends to increase rewards for quality and efficiency to 20 percent of total hospital payments in the near future.

Blue Cross Blue Shield’s Physician Group Incentive Program (PGIP) is recognized locally and nationally as an innovative approach to encouraging physicians to improve their quality of care. Program participants include primary care physicians and specialists who are board-certified, members of BCBSM’s preferred provider organization (PPO) network and who work through physician organizations on quality improvement. Each year, these organizations choose and prioritize quality improvement initiatives, provide progress reports, conduct self-assessments and report changes relative to prior periods. Physician rewards are funded by withholding a portion (3.7% as of July 2010) of physician payments. BCBSM expects to spend $65 million to $70 million on PGIP in 2010.

Through PGIP, Blue Cross Blue Shield also has a separate medical home designation process, which physicians perceive favorably. Designation is based on practice attributes and an analysis of clinical, utilization and financial performance using BCBSM claims data. Practices designated as medical homes receive a higher payment rate for evaluation and management services, with a potential increase in payments of as much as $10,000 a year for a typical primary care physician. By June 2010, BCBSM had designated 1,800 “patient-centered medical home” physicians statewide; according to BCBSM, it is the largest initiative of this type in the nation.

The Health Alliance Plan, a subsidiary of the Henry Ford Health System, has incorporated incentives for quality improvement in payment arrangements with physicians. HAP has reduced base physician payment by 20 percent, earmarking the money as incentive payments for such services as provision of after-hours care and use of e-prescribing. Beginning in 2011, HAP will reward practices meeting patient-centered medical home standards. HAP also is playing a leadership role in a statewide medical home initiative organized by the Michigan Primary Care Consortium. While currently in the planning stage, this initiative will support the use of e-prescribing and patient registries, as well as the provision of expanded access to primary care practices. To alleviate antitrust concerns that might discourage health plan participation, the state attorney general has approved this collaborative effort conditioned on the plans not discussing provider payment rates.

All of the major hospital systems are involved in quality improvement efforts. For example, they participate in various statewide programs to reduce inappropriate hospital readmission rates sponsored by the Commonwealth Fund, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the Michigan Health & Hospital Association, BCBSM, the University of Michigan and the Society of Hospital Medicine. Most have been implemented only recently, and there is mixed evidence of their success so far. In fact, some systems believe that they are working very hard to “stand still” in terms of readmission rates. Nevertheless, hospital leaders expect that Medicare, and perhaps other payers, will soon reduce or eliminate payment for preventable readmissions, underscoring the need for developing effective programs in this area. Hospitals are active in patient safety efforts as well. Indeed, several area hospitals achieved Leapfrog Top Hospital status over the last few years.

The state government has taken steps to support quality improvement efforts. For example, the state has implemented quality improvement incentives in contracts with Medicaid managed care plans, with plans with higher scores on Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measures favored in the auto-assignment process for enrollees. And, one Medicaid plan—Molina—pays bonuses to physicians for medical home and improved care coordination activities. The state also received a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation that supported the use of quality and process engineers from the auto industry to help physician practices improve productivity and quality. About 40 practices have taken part to date, with the state hoping to reach 100 practices in total.

Several efforts to publicly report comparative quality data on providers are underway. Health plans make some comparative data on quality and costs available to their members, but the amount and nature of this information is highly variable. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield only provides a listing of providers meeting the health plan’s criteria as “Centers of Excellence.” HAP attempted to provide information regarding quality of care at the individual physician level but met with considerable physician opposition on the grounds that patient sample sizes were too small to construct reliable measures. On a broader scale, a local community-based organization, the Greater Detroit Area Health Council, participates in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Aligning Forces for Quality initiative, publishing reports that compare physician quality measured at the medical group level. Health plans contribute data for this program, but the age of the data used in measure construction and the reporting of results at the medical group level limit the impact of the public reporting on provider behavior and the reports’ usefulness to consumers, according to respondents.

Health Plans and Employers Support Wellness Initiatives

The largest health plan available to residents of metropolitan Detroit is Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. The dominance of BCBSM was attributed to strong historical support from the UAW and the large discounts the health plan can command from contracting providers. The majority of BCBSM enrollment is in its preferred provider organization (PPO) product, but the plan also offers a health maintenance organization (HMO) called the Blue Care Network.

BCBSM’s two primary competitors are nonprofit HMOs—Health Alliance Plan and Priority Health—both owned by provider systems. Although Priority Health currently has a small percentage of the commercial market in the Detroit area, respondents reported the plan—owned by Grand Rapids-based Spectrum Health System—is competing aggressively on price, especially in the small-group and individual markets. Large, for-profit national health plans, including Aetna and CIGNA, are present in the Detroit market and focus primarily on serving national accounts with employees in Detroit.

Responding to demands from larger employers, the three major health plans in the Detroit metropolitan area all offer wellness and health promotion products and services. These products are regarded as a major trend in health benefits design locally and typically contain a voluntary health risk assessment, followed by enrollment of plan members in programs tailored to address specific needs, such as weight loss, blood-pressure reduction and tobacco cessation. Often, plan members receive a reward for completing the health risk assessment and for participating in programs and/or achieving goals. National health plans offer variations of these products to their customers in Detroit and throughout the United States, while Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and HAP have introduced wellness products, or features within existing products, designed specifically for Michigan employers.

Blue Cross Blue Shield offers products that provide enrollees with enhanced health benefits if they participate in designated wellness activities. The plan’s online BlueHealthConnection program contains a health assessment tool and provides an analysis of potential health risks, along with a personalized report on how to improve health. Blue Cross Blue Shield also offers a health coach hotline that connects enrollees with a nurse or other health worker to answer questions 24 hours a day. The plan offers discounts on weight-loss programs and health-club memberships through its Blue 365 program.

HAP offers a Health Engagement Program through its HMO. On enrollment, members are placed in an enhanced plan that has lower cost sharing than the standard plan. To remain in the enhanced plan, enrollees must complete a health risk assessment, meet with a primary care physician to complete a qualification form, and achieve specific wellness targets or commit to participating in health improvement programs or treatment plans. Enrollees must achieve 80 of 100 possible points to remain in the enhanced plan. These requirements must be met within the first 90 days of coverage. About 60,000 HAP enrollees are in this plan, with two-thirds drawn from Henry Ford Health System and Ford Motor Company salaried employees.

The three largest employer sectors in the Detroit metro area are automobile manufacturing (and related suppliers), the public sector and health care. While Detroit employers are engaged in wellness and health promotion activities, unions expressed concerns about the privacy of employee-provided health information and how that information might be used by health plans and employers. They also viewed some product designs as leading to unequal treatment across workers. In practice, this means that the products are marketed primarily to non-union employers or are limited to salaried employees of the unionized employers. Also of note, the current challenging economic situation for many Detroit employers has influenced their thinking about the appropriate design for wellness products. Some employers reportedly are considering the use of penalties, rather than rewards, to encourage healthy behaviors. While not common yet, employers in difficult financial straits view the use of penalties, instead of rewards, as a way to limit the costs of these initiatives.

Concerns About Safety Net Capacity

The relatively large number of uninsured people in the city of Detroit has focused attention on the ability of the health care safety net to care for the poor and uninsured. There is no public hospital in Detroit and, as a result, the uncompensated care burden is shared to varying degrees among all community hospitals and payers. The Detroit Medical Center is one of the primary safety net providers in the city. DMC’s Detroit Receiving Hospital is considered to be the largest single provider of inpatient care to uninsured adults, while DMC’s Detroit Children’s Hospital is the main safety net provider for children. Henry Ford Health System and the St. John Providence Health System also provide a considerable amount of uncompensated care. Both have relatively generous policies regarding eligibility for charity care for uninsured patients, including subsidies and discounts based on sliding-fee schedules. In 2007, St. John closed Riverview Hospital, then a significant component of Detroit’s safety net, raising concerns about the ability of other providers to absorb these patients. To this point, however, respondents indicated that there has been no evidence of significant service disruptions.

With respect to outpatient care, the Detroit Wayne County Health Authority (DWCHA) reported that in 2009, Wayne County, which includes the city of Detroit, had eight federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) with 22 facilities serving about 70,000 patients annually, with seven of the eight FQHCs located mostly or entirely in the city. Community Health and Social Services Center (CHASS) and the Detroit Community Health Connection, both FQHCs, are the largest providers of outpatient services to the uninsured, in terms of number of patients seen. As elsewhere, FQHCs receive enhanced payments from Medicaid and also grants from the federal government to provide care to the uninsured. The state Medicaid program has, to this point, avoided major cuts in eligibility and enrollment.

In addition to FQHCs, there are several free clinics that do not have FQHC status, including the Cabrini Clinic and the Mercy Primary Care Center, with the latter created following the closure of Samaritan Hospital in 2000.

Safety net providers are reporting increases in demand among the uninsured, although this varies considerably across providers. Volume increases over the past two years for FQHCs ranged from 15 percent to 100 percent, while emergency departments reported increases of less than 5 percent. Safety net providers that reported smaller increases in the demand for services suggested this may be a result of general population loss in the city and an overall increase in FQHC capacity in the past decade.

There was some disagreement among community respondents on the need to increase the number of FQHCs to accommodate the growing uninsured population in Detroit. A widely quoted estimate from the DWCHA places the number of uninsured in the city of Detroit at 250,000 but states that the FQHC capacity is 50,000 uninsured patients. DWCHA also contends that FQHC capacity in Detroit is much smaller than in other comparable cities. However, anecdotal reports suggested that many uninsured patients use hospital emergency departments (EDs) as a source for primary care.

Some respondents also were concerned about whether additional FQHCs in the community are sustainable since some are already struggling to attract patients with Medicaid coverage, a crucial funding source for the financial viability of FQHCs. Some respondents attributed the low volume of Medicaid patients at FQHCs to the way that Medicaid managed care plans were auto-assigning enrollees to primary care providers, while others cited competition with emergency departments and private providers for Medicaid patients. Hospitals do not appear to be actively discouraging Medicaid enrollees from their emergency departments because these patients increase revenue (unlike uninsured patients) and help support hospital teaching programs. Some Medicaid enrollees reportedly prefer receiving care at emergency departments, which makes it difficult to attract them to primary care providers, especially FQHCs.

The safety net appeared to be financially stable. FQHCs and other safety net clinics reported tight but positive margins, which they attributed to improved management processes and increased federal funding through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009. Some clinics also benefit from affiliations with community hospitals. For instance, CHASS contracts with Henry Ford physicians to practice in its clinics and has arrangements to refer patients to Henry Ford specialists. Henry Ford also has funded new construction, and CHASS would eventually like to integrate its EMR and IT systems with Henry Ford to increase patient care coordination. Advantage Health Centers, another FQHC, partners with St. John Providence Health System, and St. John was instrumental in helping Advantage expand from one to three sites, two of which are in St. John facilities.

Two community organizations have been established in the past decade to improve the coordination of care for uninsured residents in the city of Detroit, as well as to enhance the access to care through safety net providers. The Voices of Detroit Initiative (VODI), sponsored by the Kellogg Foundation, has worked to establish collaborative relationships among safety net providers, develop a database to track service utilization by the uninsured and establish medical homes for the uninsured. A noteworthy accomplishment has been the enrollment of 55,000 uninsured people in medical homes, typically at FQHCs, and 21,000 people in Medicaid.

A second community organization, the DWCHA, is a quasi-public agency created by the governor, the Wayne County executive and the mayor of Detroit to serve as a bridge between state policy makers and local safety net organizations. DWCHA advocates for more primary care clinics—especially FQHCs—increased enrollment of the uninsured in medical homes, enhanced funding for safety net providers, and additional cooperation among safety net providers. The DWCHA conducted a detailed analysis of the medically underserved areas in Detroit that could potentially benefit from new FQHCs. While the study identified 10 such sites, there is some disagreement as to whether new centers could be sustained given the low volume of Medicaid patients at some existing centers.

Both VODI and the DWCHA have succeeded in increasing cooperation and coordination among FQHCs. However, efforts to shift the usual source of care of uninsured people from hospital emergency departments to medical homes in FQHCs have met with only limited success so far. This has been attributed to both a lack of resources and to skepticism by some providers about the ability to change patient preferences for using the emergency department.

Issues to Track

- Will significant investments in health care infrastructure help make the Detroit area a major center for medical care and research that can help drive revitalization of the metropolitan area or will it simply drive health care costs higher and discourage employment growth by making coverage more expensive?

- Will hospital/physician integration accelerate, and, if so, what impact will this have on quality of care, efficiency and costs to purchasers of care?

- Will Detroit be able to attract and retain sufficient numbers of physicians to meet community needs?

- How will the Detroit safety net be affected by the sale of Detroit Medical Center to Vanguard? How will the safety net handle Medicaid enrollment growth resulting from coverage expansions enacted through health reform?

- Will the UAW Retiree Medical Benefits Trust, now the largest single health care purchaser in metropolitan Detroit, initiate innovative purchasing strategies, either on its own or in collaboration with other purchasers? How will Trust activities shape the Detroit health care market going forward?

Detroit Background Data

| Detroit Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Detroit Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Population, 20091 | 4,403,437 | |

| Population Growth, 5-Year, 2004-2009 | -2.1% | 5.5% |

| Age2 | ||

| Under 18 | 24.6% | 24.8% |

| 18-64 | 63.0% | 63.3% |

| 65+ | 12.4% | 11.9% |

| Education2 | ||

| High School or Higher | 87.1% | 85.4% |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 26.5% | 31.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity3 | ||

| White | 68.7% | 59.9% |

| Black | 22.8% | 13.3% |

| Latino | 3.7% | 18.6% |

| Asian | 3.2% | 5.7% |

| Other Races or Multiple Races | 1.7% | 4.2% |

| Other | ||

| Limited/No English | 4.5% | 10.8% |

| Sources:

1 U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2009 2 U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2008 3 U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2008, weighted by U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2008 |

||

| Economic Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Detroit Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Individual Income less than 200% of Federal Poverty Level1 | 29.8% | 26.3% |

| Household Income more than $50,0001 | 52.6% | 56.1% |

| Recipients of income Assistance and/or Food Stamps1 | 12.7% | 7.7% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance1 | 12.0% | 14.9% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20082 | 8.8% | 5.7% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20093 | 15.1% | 9.2% |

| Unemployment Rate, February 20104 | 15.3% | 10.4% |

| Sources:

1 U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2008. 200% of Federal Poverty Level is $21,660 for an individual in 2010. 2 Bureau of Labor Statistics, average annual unemployment rate, 2008 3 Bureau of Labor Statistics, average annual unemployment rate, 2009 4 Bureau of Labor Statistics, monthly unemployment rate, February 2010, not seasonally adjusted |

||

| Health Status1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Detroit Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Chronic Conditions | ||

| Asthma | 16.2% | 13.4% |

| Diabetes | 9.3% | 8.2% |

| Angina or Coronary Heart Disease |

4.7% | 4.1% |

| Other | ||

| Overweight or Obese | 61.4% | 60.2% |

| Adult Smoker | 20.1% | 18.3% |

| Self-Reported Health Status Fair or Poor |

13.9% | 14.1% |

| Sources:

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2008 |

||

| Health System Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Detroit Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Hospitals1 | ||

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Average Length of Hospital Stay, 2008 | 5.2 | 5.3 |

| Health Professional Supply | ||

| Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 217 | 233 |

| Primary Care Physicians per 100,000 Poplulation2 | 89 | 83 |

| Specialist Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 128 | 150 |

| Dentists per 100,000 Population2 | 64 | 62 |

| Average monthly per-capita reimbursement for beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare, 20083 | $772 | $713 |

| Sources:

1 American Hospital Association, 2008 2 Area Resource File, 2008 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians) 3 HSC analysis of 2008 county per capita Medicare fee-for-service expenditures, Part A and Part B aged and disabled, weighted by enrollment and demographic and risk factors. See www.cms.gov/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/05_FFS_Data.asp. |

||